Leah was 17 when she first flew to Montreal, in early fall of 2002, and she was scared of heights. As the plane lifted above Kuujjuaq, Nunavik, she kept her eyes on her 10-month-old daughter, Katie. She had never had a bird’s-eye view of her town, built along the Koksoak River, but she couldn’t bear to look down.

When they landed, the drive from Dorval airport to downtown seemed ugly, with endless concrete and traffic. “It’s a big city, so I thought I was going to get lost or something,” remembered Leah, whose name has been changed, along with her children’s names, to protect their privacy. She couldn’t imagine wanting to visit Montreal for fun. Going to the city was an unavoidable errand for many parents in Nunavik, Quebec’s far-north region, since their two local hospitals are too small to handle many medical procedures. That fall, baby Katie was scheduled for lung surgery.

A decade and a half later, by this past summer, everything had changed; it almost felt like Leah’s life had flipped to its mirror image. The city was more than familiar—she had slept on its sidewalks for years, homeless. Even stranger, she was nervous about the idea of going back to Kuujjuaq. The worst thing of all was that she knew Katie and her other children still needed her, but she couldn't easily go to them.

It was hard, even for Leah, to understand exactly what had happened. Each time she had come to Montreal, she had chosen to leave again and return north. Still, like a boomerang, she kept ending up at Dorval and ultimately on the city's streets. She remembered those returns to Montreal as a haze of last-minute flights, each crucial in its own way — but altogether, they had left her in the most dire crisis she'd ever faced. By last September, she had nearly given up. “I felt,” she said, “like it’s impossible to get back home.”

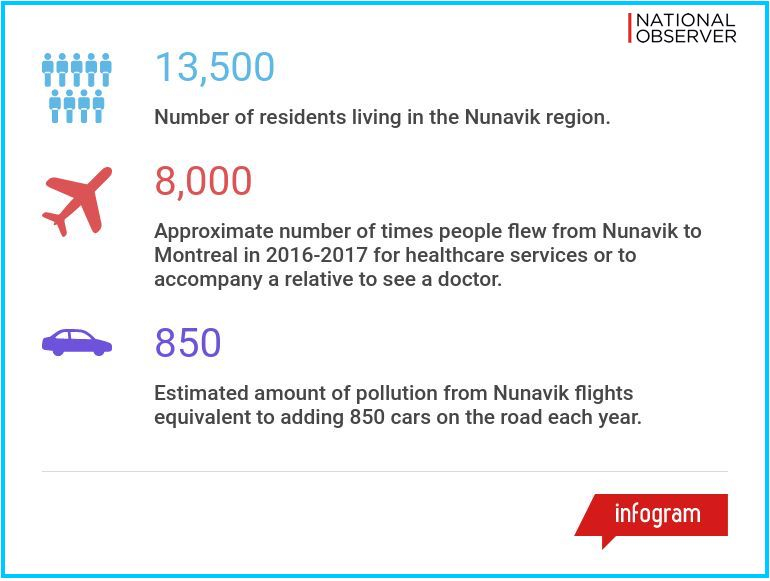

It’s common for residents of the Canadian Arctic to fly thousands of kilometres for healthcare, and Nunavik is no exception. Last year, nearly 8,000 people flew from the region to Montreal for complicated care, or relatively simple tasks such as CAT scans, or to escort a relative to see a doctor, according to Nunavik authorities. That’s 60 per cent of the region’s 13,500 residents.

While life in Nunavik has long been shaped by the policies of the south, only healthcare makes the south itself so inescapable. Inuit who migrate for school or work have the chance to plan carefully in advance. But northerners who must fly to Montreal for medical care can arrive with routines sheared off mid-day, to a world over which they have little control. As patients, they sleep in institutional housing and meet with strangers who are often unfamiliar with their home.

For many people like Leah, medical commutes have also marked the start of tragedies, some ending in deaths. For a society trying to recover from the pain of colonization, followed by the disorder of climate change, this extra source of alienation and loss makes it harder to mend the fragile social fabric.

The province says it’s difficult to provide fuller services in the remote north. But the bigger question is perhaps for a doctor: for many Nunavik patients, does southern healthcare, overall, do harm?

An anonymous escape

Leah has given birth to seven children: four who were adopted or fostered from birth, and three, all girls, whom she kept. All the times she’s left Kuujjuaq were fundamentally driven by them, she says, even if they don’t understand why. Her children sometimes say that she needed a break from them, but Leah knows the opposite has been true: she left because, when asked to live without them, she was miserable.

Leah’s life has been hard. In about 1992, when she was seven, she stopped at a cousin’s home, where his stepfather — Leah’s uncle — locked the boy in a room and “came to me and molested me,” she said. The rape changed her childhood, marking the beginning of a gap in Leah’s memory, until age nine, when she began to smoke marijuana.

She was 13 when she first got pregnant. She had Katie at 16, and her third child while still in her teens. Leah and her children lived with her mother until Leah was 17 and her mother fell ill and died. Then they moved in with Leah’s sister until the sister developed brain cancer.

Leah took on more children, becoming responsible for her sister's two kids and three foster children. By the time she was in her early 20s, she was single-handedly raising eight kids, including her own three. She felt keenly the loss of the adults she had leaned on, especially her mother, and her addictions quickly worsened.

Those circumstances meant that Leah remembers little of her kids’ early years. “I was always drinking,” she said. The Department of Youth Protection took all the children when Leah’s eldest was about 12 and Katie was 10.

Around that time, Leah’s sister needed to go to Montreal a couple of times for brain surgery, with Leah as her medical escort. On the second trip, Leah came up with a secret plan: she would ditch her return ticket and stay in Montreal.

She was desperate to escape the empty house in Kuujjuaq. “I just wanted to be numb,” she said.

She welcomed the idea of an anonymous urban escape, but she hadn’t predicted everything about life in Montreal. She moved in with a boyfriend, but he started to beat her. She survived by paid thievery, including a regular gig stealing mozzarella for a pizza place, but often went without food or shelter. Most of all, she hadn’t imagined how tightly crack would grip her. There are hard drugs up north, and Leah’s other addictions had been present since childhood. But she hadn’t tried crack until her first day downtown, when a stranger offered it.

David Chapman, the director of the Open Door day shelter near Cabot Square, said that when he met Leah, he recognized that her addiction was unusually “powerful.” He had learned by experience that the strongest addictions often go along with the most painful childhoods, and he worried about Leah, who often slept behind blue bins at the back of the shelter. Many women living on Montreal's streets are raped on a monthly basis, he said.

Leah had grieved her separation from her children, but after a year in Montreal she realized she was risking a much deeper rift. She sometimes spoke to her girls by phone, but when Leah’s siblings found out about her drug use, they cut off the calls.

She tried to arrange a ticket home and a course of rehab, but the authorities who had flown her down were no longer easy to reach. “I was too addicted,” she said. She knew she needed to call a series of people during business hours, and she wrote down the numbers, but “I kept missing the calls.” Years passed.

Making Montreal dangerous

Quebec authorities have known for decades that Inuit visitors in downtown Montreal, especially women, face certain risks. The social order around Cabot Square, where Inuit from Nunavik have gathered for decades, has been consistent since the 90s, down to the individuals at its center. This downtown ecosystem revolves around the medical system—or rather, where Inuit patients were, until recently, housed during treatment.

The healthcare offered to Inuit in southern Canadian cities is based on historical flight patterns: from Baffin Island, people fly to Ottawa, from central Nunavut to Winnipeg, from western Nunavut and the Northwest Territories to Edmonton. From Nunavik, people have always flown to the same hospitals in Montreal. Until last year, patients and medical escorts slept in a YMCA building on Atwater Street across from Cabot Square.

Three or four well-known drug traffickers and pimps frequent the square day and night. The man who offered Leah crack on the first night of her “vacation” in Montreal is “just known,” said John Tessier, an outreach worker at the Open Door. The man has spent 20 years in those few square blocks, himself homeless. Like the other non-Inuit men who frequent the square, he survives largely off the earnings of young Inuit visitors who become hooked on crack and begin to sell sex, often at his encouragement.

“Some people steal from stores… some people manipulate Inuit women, and that’s what [the man Leah met] does,” said Tessier. “That’s their hustle.”

While Leah’s experience of getting sucked almost instantly into street life is dramatic, it’s not rare. Japanese sociologist Nobuhiro Kishigami has been interviewing Inuit living on Montreal’s streets since 1996. In his most recent paper, he reported that women in particular often said they had originally arrived to accompany a friend or relative, to accompany a sick person, or to see a doctor. The people he interviewed had stayed in Montreal, homeless, an average of 10 years.

The exploitation that has grown up around medical housing has made downtown Montreal more dangerous for all young Inuit, regardless of whether they are patients. This summer, two of Leah’s friends died in the same week, both aged 27: Sharon Baron’s death appeared to be suicide, and Siasi Tullaugak’s was suspicious, with police still investigating. Leah was one of the last people to see Tullaugak before her death.

Neither Tullaugak nor Baron had arrived in Montreal because of the healthcare system. In Baron’s case, she had lived happily in the city’s suburbs for years when she first arrived. Tullaugak had gone to Cabot Square to find her sister, and Baron had gone there to visit her mother after a surgery. Like Leah, Baron was approached and offered crack the first night, waiting for a bus home. Like Leah, she became addicted almost instantly.

Last year, Nunavik health authorities opened the Ullivik Centre, a new medical housing center in Dorval, a suburb west of Montreal, and stopped using the YMCA. But substance use is still a problem; alcohol in Montreal costs a fraction of what it does in Nunavik. A report delivered in December to regional authorities said intoxication was recorded among 14 per cent of patients in the facility’s inaugural year and a quarter of the family members escorting them, or 1,400 incidents in all.

More troubling, the report also says that out of 2,602 medical escorts in the last year, two died. One was a 36-year-old woman from Puvirnituq who was run over by a truck on October 27 in the parking lot of a restaurant three blocks away from the Ullivik Centre. Police said at the time that no charges were laid because it was unclear how the victim got so close to the truck, reported Nunatsiaq News, the only news outlet to record the death. She “could have been sleeping there—we don’t know,” said a police spokesman. Police didn’t address the fact that the woman had accommodation at the health centre, a five-minute walk away. They closed the case as an accident.

It’s unclear how the second medical escort died, or his or her identity. The Ullivik Centre did not respond to a request for comment.

Though she hadn’t arrived as a patient and had fallen off the radar of Nunavik authorities, Leah was in constant contact with the health system in Montreal as her health plummeted. She was treated in emergency rooms many times after attacks by her then-boyfriend, one of which left her with a hernia from a kick to the stomach. But she says the deeper problem was losing contact with home, and her fading hope that she could bridge the distance.

She thought about her kids constantly: her oldest was in high school, Katie was starting middle school and the younger girl was still small. It had been almost three years since she left, and two years since she had spoken to them.

“I was just so tired of the streets,” she said. “I was out of control.” In November 2015, she was holding a bottle of prescription pills for a friend and decided to take them. Her friends found her on Ste. Catherine and got her to hospital, where she spent two days in a coma.

"This is incredible"

Leah remembers coming to consciousness. She felt she finally saw things clearly: no one in Nunavik knew where she was, her friends in Montreal were powerless to help, and she wouldn’t survive long. She needed to go north immediately. “When I woke up, I started realizing my kids need me,” she said. “I went to David (Chapman). I said to David, ‘Can you help me get a ticket before I die?’”

Chapman, still fairly new at the shelter, had come to know Leah better. He especially noticed a certain unusual pattern: she never stopped trying to cut herself off from drugs and alcohol, even while surrounded by them.

“I've seen Leah challenge [her addiction], and then fail, and challenge it again, and challenge it again, and keep coming back and keep coming back,” Chapman said. “Those are marks of a really strong person and a really courageous person.”

With Chapman’s help, Leah flew back to Kuujjuaq right after her suicide attempt, in November 2015, and went cold turkey. She had a court date coming up in Montreal but she was determined not to let that interfere. Two months later, arriving south, her boyfriend tried to convince her to get back together, and she simply flew him back to Kuujjuaq.

It went badly—he cheated on her and assaulted her—but she also became pregnant again, which filled her with a new resolve. She reported him to police and they sent him home. “I decided for myself, I’ve been always a single mom for 16 years; why don’t I just take care of it?” she said. Someone gave Leah an amauti, the traditional Inuit parka with a big hood to carry a baby. “I felt happy,” she said.

Chapman watched in awe as Leah willed herself through those months. He had gotten a sense of what she was like when sober—she had had often acted as unofficial spokeswoman when media visited the shelter, and he knew she was a talented seamstress. Now, she messaged him photos of the mittens and crafts she was making, and he shipped her a sewing machine. “Here's somebody who was literally sleeping...here on cement, in cold weather,” he said. “And now [she] moves back to her own community. She's got a job. She's back with her kids...And you think, this is incredible.”

Katie was 14 and Leah’s oldest daughter 16. In her vision of the future, the new baby wouldn’t just be the first child she raised sober, but the one who would help repair the family. “I wanted to have a life again with my kids, so I can prove to [child protection workers] that I can do it again,” she said.

Then there was a hitch. One morning in early winter 2016, about six weeks before the baby was due, Chapman got a call. Leah had just arrived back in Montreal.

Her old hernia, which had never been treated, was causing her pain and was deemed serious enough to send her south before the birth; normally she would have had the baby in Kuujjuaq. Chapman and Leah met up the day she arrived, making a plan for how she could get through several weeks in Montreal. But Chapman was aghast.

“I remember just thinking to myself, are you kidding?” he said. People’s social histories, their experiences in the city, don’t pop up on their files along with their medical history, but Leah’s case seemed like a no-brainer. “I don't know what the complications were,” he said, “but it's a lot more dangerous to send Leah to Montreal than to risk some complications in a birth.”

Torn in two

When doctors treat a fly-in northern patient, they don’t see what happens before or after the visit. Most importantly, they don’t always understand the tradeoffs the patient has already accepted just to make that visit, which can be incredibly steep.

On a national level, very little is known about their experiences, with poor tracking even of basic numbers, says Josée Lavoie, a professor at the University of Manitoba who has been studying medical travel for Canada’s indigenous people. Nunavik, with its 8,000 annual flights, seems to be “doing well,” said Lavoie; the Kivalliq region of central Nunavut, as one comparison, sees 16,000 medical flights to Manitoba each year for a population of just 8,300.

There are also people who, when faced with these trips, choose to forgo care, even at the cost of their lives. There is no dialysis offered in Nunavik, for example, so kidney patients, especially the elderly, have the choice to move forever to Montreal and prolong their lives, or to die at home.

In one case Lavoie is studying, a young woman--not Inuit, but from a northern First Nation--was on dialysis in the south, but needed to go home for a sister’s funeral. “She could not be transferred to another dialysis unit.. but she decided to go anyway, and she died.” The woman was about 26 years old.

In a case she remembered from Nunavik, an elder chose not to fly to Montreal with appendicitis. “He died in a very substandard care situation with no pain control,” said Lavoie. And she recalled own secretary, when she worked in Nunavut, “running around the block, pregnant at nine months.” She was trying to induce labour before she could be sent away for the birth. Seeing women trying to induce labour was common, said Lavoie.

For Leah, determined to resettle in Kuujjuaq, staying home would normally have been an easy call to make. But pregnancy muddled that question, because she wanted to make the right choice not just for herself but for her baby. And they needed different things.

After returning to Montreal, Leah held out for at least a week, Chapman said. Then she slowly slid back into her old life.

“I started drinking,” she said. “I thought to myself, ‘Oh my God, I’m going to get worse. I’m going to go back to that thing again,” meaning crack. “I asked to be induced,” she said, warning doctors that she was deteriorating.

The baby, named Ben, was born three weeks early, but not quite soon enough—Leah had started using crack a week or two before his birth.

It was a relief to have the delivery over with, and Leah, despite backsliding for a couple of weeks, couldn’t wait to return home. She gazed at Ben from her hospital bed and eventually left to scarf down some chicken salad in the cafeteria.

When she returned a few minutes later, she couldn’t find the baby. “He wasn’t there no more,” she said. “I was getting angry. I started yelling, ‘Where’s my son?’”

Crack had been detected in his blood and social workers had taken advantage of her absence to seize him for foster care.

After she left the hospital, Leah descended into heavy drug use—for a week. Then she asked Chapman to book a flight to Kuujjuaq, planning to regain custody of the baby immediately. But the night before the flight, right around Christmas, she was injured, beaten again by the baby’s father father and then struck by a car in a snowy downtown street. The car had struck her with so much force, it tore apart her boots.

In a week of intense highs and lows, with drugs and postpartum hormones flowing through her body, that night is seared in her memory. She arrived by ambulance at a hospital in Verdun and remembers sitting in the waiting room for two hours, covered in mud, while other patients stared. At four in the morning, she forced herself up to a phone, calling Chapman collect.

“I could just hear her crying,” he said. “She just said, ‘They're ignoring me, they’re ignoring me.’” She asked the other patients which hospital she was at, and asked Chapman to take her to a different one. Confused, he drove to Verdun.

“Sure enough, there she is, waiting right by the door, and you can tell the staff are eager to sort of send her on her way,” he said. They were peeking through the doors. In the car, she told him that the ambulance attendants had been mocking her in French, thinking she didn’t understand the language. They had called her an “intoxicated Inuk.”

That week she crossed two Montreal hospitals off her list of places to return to: the one in Verdun, and the Allen, where she had given birth. “I said to my ex-boyfriend, when we passed the hospital… I’m not ever going to go back,” she said. “I don’t want any memories.”

Leah had been left furious at how she’d been treated—but she was also furious at herself. Her own instincts for the baby, she saw in hindsight, had been so wrong: going to Montreal in the first place, and then expecting everyone to understand how she was trying to keep him safe. “I didn’t think they were going to take him away,” she said.

Leah’s life had flipped back to its mirror image; Montreal felt ordinary, and Kuujjuaq felt unattainable. She didn’t make it onto her flight the next morning. Returning north a few months later, she felt herself losing willpower to get through withdrawal and chose to return to Montreal rather than allow her children to see her under the influence.

Eight months after his birth, Ben was still living with his foster family, and his mother was on the streets near Cabot Square.

"Even if it means that your life is shorter"

The goal of the Nunavik health care system is the same as the goal across Quebec, said a spokeswoman from the provincial health department: to maintain a high, consistent standard of care, no matter the geography.

“The decision to transport patients to Montreal was made not for economic reasons, but because of the low population volume in Nunavik, which does not allow to offer a wider range of specialized services,” spokeswoman Marie-Claude Lacasse wrote in a statement. “Transporting patients to the south allows people who live in remote areas to benefit from high quality care, like other Quebecers.”

The disadvantage is that patients have to travel, sometimes several times, to get that care, she added. She didn’t go into detail about how serious the province considers that drawback.

In Nunavik, the system may be funded by the province, but it’s run by the regional government out of Kuujjuaq (the federal government declined to comment, saying Nunavik’s healthcare falls outside its jurisdiction).

For Minnie Grey, the executive director of Nunavik’s Regional Board of Health and Social Services, being treated “in proximity to your land” is crucial, and increasing local services is a main goal. Nunavik's two local hospitals are not currently equipped to provide CT scans or MRIs, for example, and no surgeons are based there. “We won't be able to treat trauma, we can't do heart surgery, we won’t be able to do chemo,” said Grey. “But there are a lot of other specialties that can be repatriated.”

Medical travel currently costs the Quebec government $20 million a year, in addition to renting the Ullivik Centre for $2.5 million annually. If a bigger hospital had been built 10 or 15 years ago, Grey says, it could have paid itself off by now in saved travel costs.

The idea hasn’t been rejected, Grey said. Lacasse, from the provincial health department, said a review of Nunavik’s health system is underway and it’s too early to predict the outcome. But bureaucratic lethargy moves extra slowly in the north, Grey says. Any construction would be slowed by bigger infrastructure questions like power and internet availability, and by the short building season. “If it takes four or five years to get approval for a small [community clinic],” Grey said, “can you imagine how long it will take to get our regional hospital?”

Some medical travel is inevitable. But to talk to health professionals, there are also workarounds--small changes and investments--that would bring fuller care to the north.

The provincial spokeswoman pointed to a common limitation: scarcity of staff. It can be hard to recruit for the north. A young nurse, who didn’t want to be named for fear of job repercussions, said that it’s a vicious cycle where chronically low staffing leads to burnout. The nurse, who spent two years working in one of Nunavik’s small villages, said she worked 50 to 80 hours a week, sometimes doing 26-hour shifts without a meal.

The people she met were “so inviting... so resilient,” she said. But “there's so much suffering underneath that.” With no hospital in the community, she was running a one-woman emergency room overnight, knowing people might show up in the midst of a crisis, threatening their own lives or hers. She started feeling constantly stressed, even at home, where she began sleeping facing her door. She quit after two years.

Lavoie said that staffing the north with experienced, well-equipped nurses would eliminate many unnecessary flights, since patients are often sent south as a precaution when the referring nurse is nervous. But a solution could also be as simple as coordinating appointments better, so the same person doesn’t fly south for three follow-up appointments and separate bloodwork.

Better hospitality for patients would also help ease the strain on them. Ottawa’s Inuit medical housing facility, with its small school, is an example of one working well, said Lavoie. Another current experiment is “robot doctors” in northern Labrador that allow patients to talk to southern doctors through a screen in real-time.

Sara Goulet, a family doctor who works in northern Manitoba and Nunavut, said there could be an even easier way to get expert advice without a flight. In Nunavut, medical travel costs more than in Nunavik—tens of millions annually.

“There are times when, if I just had access to an immunologist or a rheumatologist to ask questions to...the patient probably doesn’t have to leave,” Goulet said. With advice, she could do bloodwork and bring in medications. But the specialists aren’t compensated for that kind of real-time consult, said Goulet. They can bill at least $100 for an in-person visit, but only about $15 for a phone call, so their days are not set up for the type of long reviews Goulet would need. Provinces would need to change their billing systems to allow it.

Working in Nunavut taught Goulet, who is Métis, that it's hard for outsiders to put a price on the ability of northerners to stay home, when Inuit patients are sacrificing their own health for it. “Inuit are so tied to their land base,” she said, echoing Grey. However hard it is, watching people decide to forgo the treatment was “sort of beautiful” too, she said. “That you choose your culture and your family and you want to be around those things, even if it means that your life is shorter, because it gives you such a powerful quality of life.”

No solutions are coming fast enough for the pressure growing on the Nunavik system, with the population growing faster than anywhere in the country. In the last couple of years, the number of medical trips has almost doubled, said Grey. The 143-bed housing centre has been full since it opened, with spillover in hotels costing $100,000 a month.

Climate change is also creating extra health problems in the far north. Wild meat, water sources and travel can all be increasingly hazardous, according to a recent study funded in part by Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, the national nonprofit representing Inuit.

“Ivujivik and Puvirnituq residents are concerned that more people are eating less country foods and there is worry that more people are getting sick more often as a result,” said the report.

Natan Obed, president of the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, recently noted that people in the Arctic have to work around industrial coal pollution, with mercury contaminating local food. “These are things that we didn’t create, but these are things that we are challenged by,” Obed said last November at the United Nations climate change summit in Bonn, Germany.

It’s ironic, in a way, that the 8,000 return flights from Nunavik to Montreal last year hastened climate change. According to the National Observer’s calculations, those flights added 4,000 tonnes of carbon emissions, or the equivalent of putting 850 extra cars on the road per year.

The most optimistic girl

By August of 2017, Leah had started wondering if she should stay in Montreal forever. She’d lost strength, she said, and she hated to return home in the throes of addiction. But she was also scared about how it would affect her daughters if she tried to go home one more time.

She worried in particular about Katie, then 15, the most optimistic of her girls. In the years her mother was away, Katie had rarely let a call or Facebook message go by without asking the same question: when are you coming home? And every time Leah did come home and then left, Katie had been devastated. Leah worried the teenager couldn’t handle another heartbreak.

It ended up being Katie who changed her mother’s mind. Over the phone, she told Leah she had been feeling very low, and Leah sensed that it was serious. Panicked, she landed in Kuujjuaq in September.

The flight home, like the one she first took to Montreal, is also lodged in her memory. Siasi Tullaugak and Sharon Baron had died days before, and Leah cried through the trip, thinking about them. Nauseous from withdrawal, she was desperate to see her children, but also dreaded their reaction. “I was shaking—I was so skinny,” she said. “They saw me in my miserable way.” She had a plan: first, go to rehab for a month. After that, spend time with the girls, and don’t leave Kuujjuaq for any reason.

At 32, Leah had become a grandmother twice over. Her 18-year-old daughter, in an echo of her own life, had custody of her two younger teenage sisters, her own two babies and some foster children. Leah knew they had been struggling, but only when she moved in did she finally begin to understand how dire things had become in her long absence.

Her family told her they had been getting strange calls from places like the Kuujjuaq hockey arena. Katie was there, covered in blood, the callers would say. The rest of the story came as a relief to Leah, followed by horror. Katie had been buying fake blood in a tube, a Halloween prop. She was picking the town’s most public spots and staging injuries. Her family realized that she was desperate to be flown to hospital in Montreal. “She wanted to come see me,” Leah said quietly. It made her frantic to think that Katie saw a medevac as her only way to reach her mother.

Worse, Leah learned that Katie had another option in the wings: she had been messaging on Facebook with a man who had contacted her from Montreal, claiming to know Leah. He must have seen photos of Katie, a pretty girl with shiny side-swept bangs, on Leah’s Facebook page, said Leah.

The man told Katie that he wanted to fly her down to Montreal and marry her. He promised to bring her to her mother, saying Leah would permit the marriage in exchange for drugs. Leah was stunned to think Katie believed this. She also saw, after her efforts to keep her children 2,000 kilometres from her addictions, how present they still had been.

Now, Leah is taking stock of the decisions that seemed right at the time—to stay in Montreal in the first place, to fly back there to give birth. She knows that if she’s struggling to fathom how it all happened, she can’t expect Katie to understand just yet. “She was feeling unwanted,” Leah said. “I’m just telling her that I'm here now. I’m not going to leave.”

Within three months of arriving home, Leah was working full-time and attending endless meetings in an effort to regain custody of baby Ben. She also has a doctor in Kuujjuaq, whose main prescription is for her to remain north. Leah still needs her hernia repaired, but the doctor confirmed that she was postponing the surgery.

“I think for her global health it's better, for now,” said the doctor. “It's better to be home than in Montreal on the streets.”

Still, while life is happier, it isn’t simple. Katie, who turned 16 this fall, had a surprise for Leah the day she came out of rehab: she was pregnant. “We can get through this,” said Leah. “I’m going to be there every step of the way.”

What will happen if Katie needs to go south to give birth? Though Leah has promised to stay by her daughter's side, she also needs to show child protection workers that she’s learned her lesson about well-meaning trips south. “I’m proving them wrong,” she said. “I’m here. I’m always here."

This article was produced in collaboration with the Echo Foundation.

Comments