Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Author J.B. MacKinnon went up to Burnaby Mountain on the weekend to protest against Kinder Morgan's plans to run a second pipeline through one of Burnaby's most cherished conservation areas.

He was arrested for crossing into the Kinder Morgan drilling site currently under injunction by the B.C. Supreme Court, becoming one of the first in a growing series of prominent public figures to take action and get vocal on Burnaby Mountain.

MacKinnon spoke to The Vancouver Observer after he had spent some time walking in the sun and "breathing the air of freedom" on the morning after his arrest, on the personal reasons for why he crossed the police line after the court granted Kinder Morgan an injunction.

MacKinnon is a Canadian journalist and literary figure and is well-known for such environmentally progressive works as his latest book The Once and Future World (a national bestseller that won the U.S. Green Prize for Sustainable Literature). He also helped spark a local eating trend with the 100-Mile Diet.

From observer to participant

Yet as far as environmental protest goes, he has normally been the observer documenting and commenting on events, rather than the one getting arrested on the front lines:

"I attended the protests in Clayoquot Sound as a journalist, I attended the big demonstrations that happened against APEC, at UBC and the Gulf War as a journalist; I was present at the Battle of Seattle in 1999 as a journalist," he said. "This was the first time that I felt that I actually needed to cross the line from observer to participant."

When asked what compelled him to make this transition from observer to participant, MacKinnon suggested that the decision was partly based on how best he could contribute to the cause at this point in time.

"[I've] had the sense for some time that it's not a lack of words on paper or a lack of ideas that's preventing us as a society from moving forwards and addressing climate change as the most urgent issue of our time," he said.

Accordingly, he concluded that "getting another article out there wasn't going to be as valuable a contribution as actually putting myself on the line with all those other people who had made the difficult decision (to get arrested)".

MacKinnon said he joined the protests for the first time on Friday (he was out of town on Thursday), and realized that protesters "were being arrested for things that I believe in. They were being arrested at a time that I think action is important and I felt that I needed to join with them."

Then, he said, "it really came down to a sleepless night."

"Quite literally, I had an almost sleepless night after Friday and then I just woke up in the morning with a clear decision in my mind that I was going to go out there and get arrested. I spent that night thinking about how the consequences could play out in my life. I came to the conclusion that I was ready to face the consequences in order to make this particular statement."

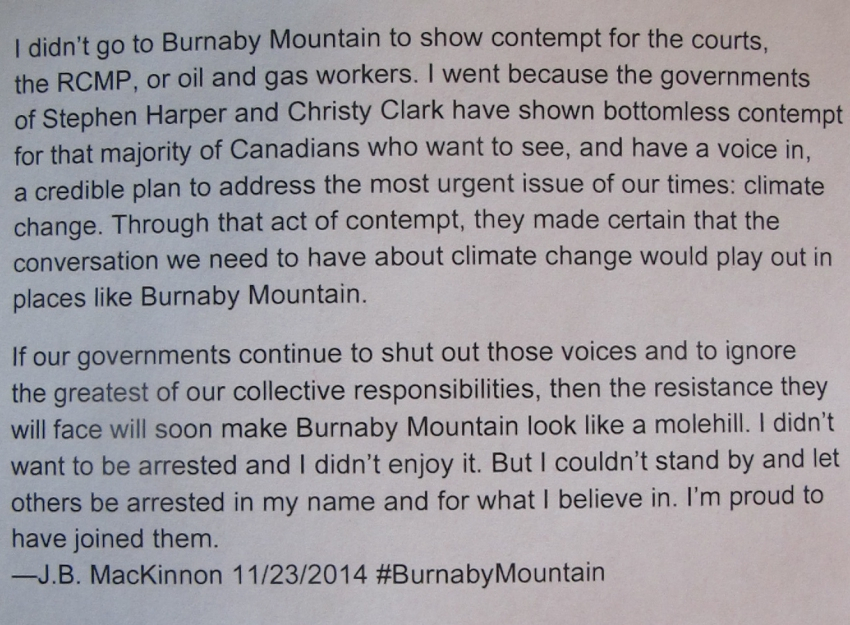

When you watch the footage of a plasti-cuffed MacKinnon being informed of his rights by an RCMP officer after being taken into police custody, the clarity of purpose and calm resolve won at the cost of this sleepless Friday night seem evident in his manner. The statement he issued to the Vancouver Observer after being processed and let go by the RCMP demonstrates a similar degree of quiet determination:

VO Exclusive: MacKinnon motivations for arrest #BurnabyMountain #KinderMorgan via @VanObserver http://t.co/ZKZGvWB1cO pic.twitter.com/93sOFJyIBN

MacKinnon suggested that amongst those who have been arrested while protesting on Burnaby Mountain he is not unusual in going through a period of lengthy deliberation before committing civil disobedience: "There's this perception among some people out there that people take this lightly and that the decision is not consequential and those people are simply wrong. It's something everyone I've spoken to who has been arrested took very seriously — I certainly did."

A collision of private and public spheres

For him, crossing the injunction boundary line to be arrested was also a deeply personal, private moment: "I didn't want to pump my fist. I didn't feel the urge to raise my fist or make a statement to the crowd. I have all kinds of respect for those who do that, but for me it was just more of a private experience."

It was intriguing to hear that MacKinnon primarily experienced his arrest as a private experience, since his profile as an author certainly made his arrest at the Burnaby Mountain protests highly public and symbolic. Yet this is precisely the complexity of the arrest experience he went through on Saturday, and further discussion of what struck him most about the arrest and processing experience revealed that the complexity of this experience goes beyond even the collision of private and public worlds:

"What stuck out for me the most is probably the light-heartedness that everyone felt after being arrested. I think sometimes that's been misconstrued by people as arrestees taking the situation lightly or not having seriously considered what they're doing. But I think that light-heartedness comes from the relief you feel at having taken a step that all of us have probably thought about taking for longer than we even knew. Certainly, if I compare the sleep I had the night before I was arrested with the one I had the night after I was arrested, I know which one was the more restful sleep.

"There's a joy and a freedom that comes with being true to yourself. That's the lightness that people are observing in the protesters. As I say, I think that some people, when they see people smiling or laughing amongst each other, or singing, they think 'oh these people are goofballs,' but it's a very liberating moment for most people. By the time they've taken that step and been arrested they've done all the serious work and they're in the mood to be free."

This light-heartedness can be observed in MacKinnon and his fellow arrestees as well once they've been escorted further into the drilling site and stood in a line by police officers to await processing — they seem to be joking, greeting one another in excitement and attempting to shake hands while wearing the awkward plasti-cuffs.

MacKinnon is also straightforward about the fact that the part where he was held in a cell by the police at the Burnaby RCMP detachment was not at all an enjoyable experience. Speaking of how, after arrival, they were "slowly unloaded" then "sat in our cells for hours and hours and hours" before finally being processed and released, he said that the whole ordeal was "completely new for me, and I found it extremely unpleasant."

"I don't think anybody enjoys having any part of their time or their person under the control of the RCMP. It certainly wasn't something I looked forward to and I didn't enjoy it."

Facing such an extremely unpleasant consequence for his actions, one wonders what motivated MacKinnon to risk arrest. When this question is put to him, MacKinnon responds with certainty, and his answer is convicted:

"I think there are a lot of people out there who have come to the conclusion that governments and corporations aren't going to budge on climate change without a serious confrontation, without it being driven by very committed people."

"I think our best hope is that this change can happen through mass, peaceful civil disobedience. If that doesn't work, it's possible things will get even more serious."

"What's happening at Burnaby Mountain is that at one level it's a fight about Kinder Morgan drilling two bore holes in the ground, but that's clearly not what people are on the mountain for. They're on the mountain because they're tired of this relentless push towards ever more fossil fuel infrastructure without a hint that our government is prepared to address the most urgent issue of our times."

For MacKinnon, this is the key concern and catalyst drawing such a large number of concerned citizens from Burnaby, Vancouver, and further afar into the Burnaby Mountain protests:

"I think the broadest scale point that really unites everybody who goes to Burnaby Mountain to protest is that climate change is the issue here. There are all of the local level issues and issues of jurisdiction and questions about process, but I think that the root of the anger is the sense that for 20 years people have tried everything, every means imaginable, to get governments to move off of the course of a fossil fuel driven economy and towards something more sustainable and nothing has worked. So people are feeling driven to take more committed action."

Canada's role in the climate change fight

As the protest on Burnaby Mountain continues to evolve and form stronger links with ongoing environmental and First Nations protests at other sites and regions across the country, a sense is starting to emerge that it is time for Canada to step up and either redefine itself for the future or continue to be perceived by the international community as an environmental villain.

It is with this in mind that I ask MacKinnon to comment about Canada's role in the climate change fight, and whether there is a special Canadian spirit that may be adventurous enough to undertake the task of rebuilding our national worldview and renovating our international image. MacKinnon had some interesting insights:

"Canadians have an appreciation for the ecological world that we call nature that we probably don't even recognize in ourselves. It's very strong, but it's so much a part of who we are that we often don't recognize it. I've seen throughout my life of observing environmental issues that this is very much the foundation from which so much Canadian political action comes."

"The other thing in terms of our position as Canadians, is that we do have the very good fortune to have a police force that is largely civil, that shows restraint. That treats us for the most part as citizens. We have democratic processes that protect us. We are a privileged people, and if we're not prepared to take these kinds of committed actions then we're leaving them to people in places where the police forces are far more dangerous and the democratic processes far less fair."

Could the type of actions taking place on Burnaby Mountain be a way for Canadian citizens to reverse the image of Canada in the world today as an environmental villain?

"I've been asked several times to write articles to try to explain to Americans why Canada has turned sour. I've been asked to write on the subject of 'what's happened to Canada?' 'What's happened to this Canada that we knew?' I've always drawn away because Canada's environmental history is spotted and complex and I'm not prepared to just say that Canada used to be great and now it's bad, bad bad.

"The way Canadians relate to the environment at home has always been complex and not all good and not all bad, but overall we were seen as a force for good by the international community. I think now, overall, we're seen as a force for ill. On so many fronts, not only the environment."

"I've been thinking hard about what the shift has been — and I'm still thinking through it — but I think what I'd like to say about Burnaby Mountain is that there are a lot of people out there in the rest of the world who have been saying what happened to the Canada that we know, and they will see that more familiar Canada in action in places like Burnaby Mountain."

Looking towards the future

MacKinnon is set to appear before the court to face the charge of civil contempt on the 12th of January, alongside the majority of other protesters who have been arrested for civil disobedience on Burnaby Mountain. In the meantime, although he is "a working person too" and has to make his living, he is "certainly going to try to get back out there to act in a supportive capacity for other people and to continue to be a part of the presence there."

Acknowledging that "protests have a real life of their own," MacKinnon suggests he has no idea how events on Burnaby Mountain will develop. All he has to say on this account is "so far so good." He does, however, hope that the protests will ultimately have a widespread impact and resonate with people long into the future:

"Who knows what will happen with this thing on Burnaby Mountain but I think it's definitely fair to say that momentum is still building, and even after the drilling stops, I hope that an example will have been made that people will take up in their own local communities in their own fights against the same thing: this relentless push towards ever deeper entrenchment in the fossil fuel system without any plan to address climate change. I think that's what people are trying to fight towards."

"We can't reduce this argument to this pipeline or that pipeline. The argument is: are we going to let our government totally and ever more deeply entrench us in the fossil fuel economy of the past without taking any responsibility for building a sustainable economy for the future? That's the issue. It's not one particular pipeline versus the other pipeline, or one coal port versus one fracking station, it's all of it. People are fighting it at the local level but they have that global sense of it in mind."

Comments