Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Kenneth Francis was six when his father’s job-search experience became a lesson that would shape the rest of his life.

Circa 1950, Joseph Francis, a member of the Mi’kmaqs’ Elsipogtog First Nation, was travelling all over his native Kent County, New Brunswick to find a job. He came home ecstatic one evening because he had finally found work at a lumber mill on the Miramichi River. But the elation did not last long.

A few days after he started working, the foreman told Joseph that if a white person came up the road also looking for work, he would have to let him go.

The job lasted two weeks.

Joseph was “deflated and hurt,” Francis remembers. He stopped looking for employment and decided to become self-sufficient any other way he could. He made baskets, harvested blueberries and potatoes, caught fish and dug for clams.

It’s a lifestyle he passed on to his five children.

“He gave us all a very good life,” Francis said. “That’s more or less what we tried to do. We didn’t want to depend on anybody else for a job.”

Francis says he grew up wondering how it was that his people owned so much land and yet were so poor. His father reminded him often that the Mi’kmaqs never ceded their territory to the European settlers — a fact confirmed by the Supreme Court in 1999.

So, when SWN Resources, a Texas-based oil and natural gas company, began testing for fracking opportunities around Elsipogtog three years ago despite protests from the natives, Francis began researching how to protect his home. He looked at how other Indigenous people across Canada had won land claims.

In the summer of 2014, he got inspired by Tsilhqot’in Nation's legal challenge, which resulted in their being the first First Nation in Canada to receive an Aboriginal land title over unceded territory. Francis decided he too had go to court to assert legal ownership of the Elsipogtogs' land.

In the coming weeks, Francis hopes to retain a lawyer and file legal papers on behalf of the people of Elsipogtog. His primary goal is to ensure that the Elsipogtog are consulted in a meaningful way before corporations and governments begin development projects that would affect their natural resources. Francis suspects that receiving an Aboriginal title is the only way to achieve this.

His plan for legal recourse comes during an economically uncertain time for New Brunswick in the energy sector. Just two months ago, the province’s newly elected Liberal government fulfilled their campaign promise to place a moratorium on fracking, a controversial process to extract natural gas from shale rocks.

In recent years, about 10 companies have held licences to search for shale gas across approximately 1.4 million hectares. Corridor Resources Inc., a natural gas and petroleum company that has been fracking for a decade about 150 kilometres south of Elsipogtog, told CBC that the moratorium could force the company out of the province and affect hundreds of jobs.

Meanwhile, SWN is forging ahead with its exploration activities by drilling wells for rock samples in Kent and Queens counties this year.

Fracking, or hydraulic fracturing, involves blasting a toxic brew of known carcinogens, water and sand at high pressure into the ground to break up shale rock formations and release natural gas. There have been documented cases of methane released from fracking leaching into drinking water.

Hundreds of tanker trucks needed to carry millions of gallons of water and other supplies add to greenhouse gas emissions causing respiratory illnesses in people living nearby. In Kent County, SWN has said their practices are safe and provincially regulated, but Aboriginals fear the process will pollute the Richibucto River where they catch trout, eels and bass throughout the year. Children splash around in it during the summer, just as Francis did when he was younger.

Premier Brian Gallant has said the moratorium won’t be lifted until the province has credible information on the impacts of fracking on health and the environment and a process to consult with First Nations has been created. This is essentially what Francis is looking for, but he says it’s not enough. Governments change and other companies beside SWN will emerge, he says, and the people of Elsipogtog need to be in control of decisions that affect their land.

A land title for the Elsipogtog could thwart SWN’s ambitions in the area. If Francis wins, it would be another victory for First Nations in a long series of cases in which courts have sided with them and reaffirmed their constitutional rights. But many within the Aboriginal community argue that the courts give them limited powers because Canadian law has never fully recognized their sovereignty.

It is not known just much leverage a land title may give the Elsipogtog. In the precedent-setting Tsilhqot’in case that inspired Francis, Canada’s top court granted the first and only Aboriginal title in the country to the First Nation, but the province still holds the underlying title.

Bruce McIvor, an indigenous rights lawyer with First Peoples Law in Vancouver, explained that although previous court rulings established an obligation for governments and industries to consult with First Nations before potentially infringing upon their rights, the Tsilhqot’in decision shifted the duty to consult toward a greater obligation to actively seek consent in good faith.

“What the court has said about consent is that if one can establish Aboriginal title, you should be getting their consent. Short of it, you should at least try to get their consent,” McIvor said.

But Arthur Manuel, a leading political activist and former chief of the Neskonlith Band in B.C., says the duty to consult is “toothless” because it doesn’t require accommodating First Nation interests, and governments have a history of disrespecting treaties and court judgments.

“In all of Canada, the underlying title should be Aboriginal,” Manuel said. “That’s the only way you can decolonize Canada. It’s an inalienable right of Indigenous people.”

While court cases pressure companies to stay away from Indigenous lands, Manuel says the United Nations should be the final body to resolve the issue of First Nations right to self-determination and that is where Aboriginals should be heading.

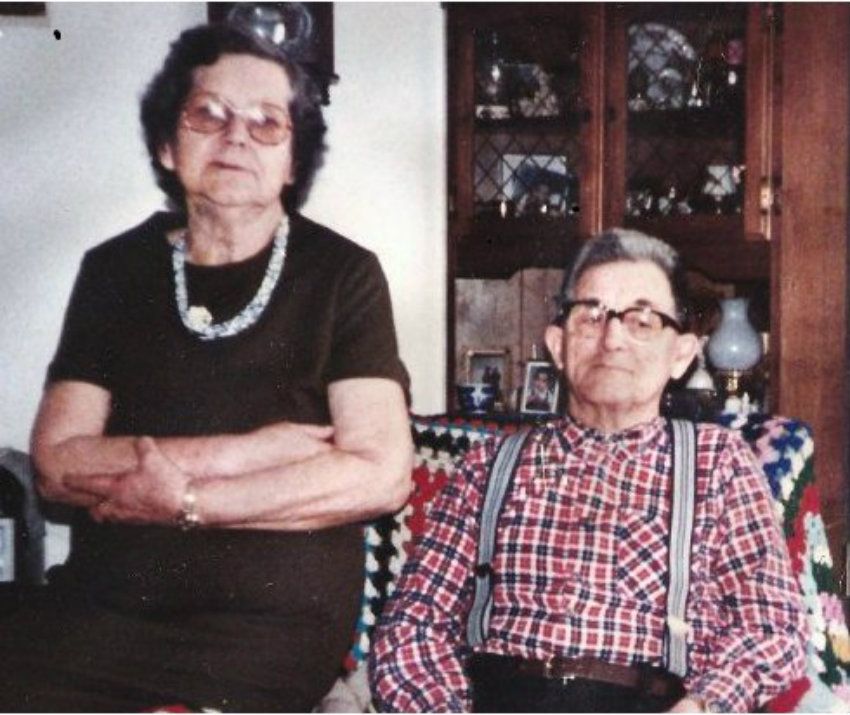

For now, Francis is putting his faith in Canada’s legal system. At 70, he says he does not have much to gain personally if his plan succeeds. His three sons are grown and have moved off the reserve.

But he remains guided by the Mi’kmaq belief that the planet should be preserved for future generations and he hopes that acquiring an Aboriginal title can prevent fracking, protect the Richibucto and preserve his people’s traditions.

“We have borrowed this land,” he said. “We didn’t inherit them from our fathers, we borrowed it from our children. So, we have to make sure it is in proper condition when they get it.”

Comments