Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Is Canada’s finance minister, Joe Oliver, seeking economic advice from a scandal-plagued corporate honcho?

Oliver, who is also MP for the Toronto riding of Eglinton-Lawrence, can’t be a happy man these days: Canada has slipped into recession again, blowing a hole in his hopes of balancing the government’s budget for the first time since 2007.

But Oliver’s mishandling of the economy might not be a surprise given the quality of the some of the people he relies on for advice – such as Rebecca MacDonald, founder and executive chair of Just Energy Group Inc., a $3.9-billion Toronto-based energy marketing company. Oliver appointed MacDonald to his Economic Advisory Council last summer.

MacDonald was in the news last month after Canadian Pacific Railway Ltd. made her the head of its corporate governance committee. MacDonald has been on CP Rail’s board for the past three years.

Yet MacDonald is also a highly controversial figure within the business world, overseeing a company that is regularly pilloried for its unethical behaviour.

“I am baffled by both the Oliver appointment and the [CP Rail] governance position,” says Dr. Al Rosen, one of Canada’s leading forensic accountants who has investigated Just Energy and MacDonald.

In fact, charges of consumer fraud, unscrupulous sales tactics, multi-million dollar fines, and allegations of fabricating credentials have plagued both MacDonald and Just Energy for years. This past winter, for example, Massachusetts forced a US$4-million settlement out of the company over its sales methods, specifically over making false representations to customer.

“We allege this… supplier engaged in widespread and misleading conduct that lured consumers into costly contracts in the form of high electricity rates and termination fees,” said the state’s attorney general, Martha Coakley, when the settlement was announced.

And the Ontario government introduced a bill this year to ban the kinds of contracts Just Energy peddles to consumers at their homes because they're seen as being so detrimental.

Just Energy is an energy marketing company that doesn’t actually produce any energy itself. Employing armies of door-to-door salespeople, it merely offers customers contracts for gas and electricity at fixed rates. The selling point is giving customers peace of mind, knowing that their energy costs won’t suddenly go up. Just Energy has signed up 4.7 million retail and commercial clients in Canada, the US and UK.

Yet, due to falling energy prices and mismanagement, Just Energy is now in the ditch, posting a $443.7-million net loss last year, with deficit and liabilities amounting to $1.3-billion. Just Energy has cut its dividend in recent years, and its stock has plunged from as high as almost $14 in 2012 to as low as $5 last year.

“It’s a company that’s treading water and the water is getting choppy,” says Anthony Scilipoti, CEO of Veritas Investment Research, a Bay Street equity research firm.

Just Energy also owes $105-million to the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB) – a loan it received three years ago after Bay Street refused to finance the company in a public share offering. The CPPIB invests money to enrich the CPP system, but Rosen now worries the board might not get its money back. “How they could possibly have loaned them five cents is beyond me,” he says.

The answer may lie in the close ties MacDonald has with the leadership of the federal Tory party – with people like Oliver and her close friend John Baird, Harper’s former foreign minister, who recently joined her on the board of CP Rail.

Overall, MacDonald’s track record speaks volumes about the sort of business leaders the Tories favour.

Tall tales about her past?

Now 61, MacDonald is one of Canada’s wealthiest and well-connected women, living in a sprawling mansion in Toronto’s tony Bridle Path neighborhood. There she’s hosted fundraisers attended by the likes of socialite Suzanne Rogers, Bata shoe empress Sonja Bata, CBC hipster George Stroumboulopoulos, entrepreneur Ron White, Belinda Stronach, Kevin O’Leary and Tim Horton’s co-founder Ron Joyce. Her social clout was reflected when she hosted Prince Edward and his wife, the Countess of Wessex, at her home in 2012.

Other pals include Major General Lewis MacKenzie, former Senator Hugh Segal (who sits on Just Energy’s board) and former Ontario chief justice Roy McMurtry.

MacDonald also owns a 40,000-square-foot villa, built for US$20-million, located in the Orchid Bay Estates gated community in the Dominican Republic, to which she commutes on her private jet and where she’s entertained friends like Baird.

Until recently, MacDonald sat on the board of the Royal Ontario Museum and is the recipient of an honourary doctorate from the University of Victoria. PROFIT Magazine named her Canada’s top woman CEO from 2003 to 2008, while she’s received the Ontario Entrepreneur of the Year award from Ernst & Young and the International Horatio Alger Award

Still, what few of her establishment pals may realize is how she’s fictionalized her past: Born Ubavka Mitic in the former Yugoslavia, MacDonald has claimed her father was an energy minister in the government of Yugoslavian dictator Marshal Tito.

She’s said she trained to become a concert pianist and completed a medical degree by age 22 before emigrating to Canada in 1974. And she came to Canada by fluke – after the American embassy turned her away.

Most of this narrative is untrue, according to MacDonald’s first husband, Dr. Mike Jankovic, a professional engineer based in Calgary. Jankovic says he initially met MacDonald in Yugoslavia in 1974. He says no one ever suggested to him MacDonald’s father had been a minister in Tito’s government: instead he worked as a mining inspector and lived in a rundown 500-square-foot apartment.

“Her father was never, to the best of my knowledge, the minister of energy,” says Jankovic. The public record shows no evidence of this either.

Jankovic also says MacDonald initially told him she was attending medical school. But after he spent $2,000 to bring her to Canada and they were married, Jankovic says she confessed to him she hadn’t attended medical school or even university. And she never demonstrated she could play piano.

“That’s how my marriage started,” says Jankovic. “It started with a big lie.” Jankovic has since received independent verification from the University of Belgrade that MacDonald did not attend its medical school.

Telling fibs about your credentials is not a minor issue if you’re running a publicly-traded company, says Joe Groia, one of Canada’s top security lawyers.

“If you have a director or an officer of a public company who’s falsified her credentials or if she’s telling stories about her background in order to give herself credibility in the marketplace and those stories are not true, that’s a very serious issue… So regulators take it very seriously… because directors have a huge amount of responsibility.”

The marriage with Jankovic lasted four unhappy years and ended in 1978 when MacDonald left him for his best friend, Pearson MacDonald. Jankovic has never spoken to her since. MacDonald, meanwhile, has characterized Jankovic of having a “personal agenda” against her.

Fast forward to 1986, after Ontario’s natural gas industry was deregulated, and MacDonald saw an opportunity. Energy marketing firms were offering energy contracts to consumers by convincing them to sign four to five year contracts that set their gas or hydro at a fixed rate. They often claimed the consumer would save money by doing this.

But these companies have a fatal flaw: if energy prices fall, consumers see no reason to lock their contracts in for a fixed period of time.

MacDonald’s first company in the sector fell victim to this reality and collapsed in the early ‘90s. She then started a new company which eventually morphed into Just Energy.

Yet fluctuating energy rates means that energy marketing companies can’t guarantee any savings to customers at all. Barbara Alexander, a former director of the consumer assistance division of the Maine Public Utilities Commission, says companies like Just Energy mislead customers about savings in their contracts.

In testimony she gave against Just Energy in a 2008 legal action, Alexander concluded that “almost all of [Just Energy’s] plans have cost customers far in excess of the regulated natural utility gas supply charges.”

Still, with energy prices rising after 2001, and structured as an income trust, Just Energy took off and became a darling of Bay Street – and made MacDonald a very wealthy woman.

Soon, though, the inherent problems of how her company made money began to emerge.

Just Energy sales methods condemned

One reason companies like Just Energy are problematic is because their door-to-door salespeople don’t receive salaries – but survive solely on commissions. This gives them an incentive to use all manner of means to get people to sign up contracts – often unethical ones.

Alexander testified that Just Energy’s sale staff would often make false claims about their contracts saving money or would say they worked for the local utility.

“[Just Energy’s] agents took advantage of elderly, confused, frail, disabled and non-English-speaking household members,” she said. “[Just Energy] has made exorbitant profits from its marketing model… and has charged unfair and unreasonable early termination fees when customers sought to cancel the contract.”

In one documented case, a Just Energy salesperson signed up a disabled senior in Illinois for a five-year contract at US$1.19 per therm of heat – while the local utility was offering it for only 59 cents. The Citizens Utility Board (CUB), a consumers’ watchdog in Chicago, has estimated that more than 90 per cent of Just Energy’s contracts lose money for their customers.

Meanwhile, the Better Business Bureau (BBB) in Central Ontario refuses to register Just Energy because of their dubious track record, giving it an “F” ranking. In the past three years, the BBB has closed 547 customer complaints about Just Energy over its sales tactics.

“The complaint activity is consistent – we don't see any reduction in the numbers,” says Ric Borski, president of this BBB chapter.

"Slamming" to get contracts

But the most controversial tactic the company has been accused of using is called “slamming.”

“Slamming is the process where you switch someone to a service that they didn’t authorize,” says David Kolata, executive director of CUB.

“We’ve received through the years a significant number of complaints around slamming about Just Energy… We’ve received complaints along the lines of someone going door-to-door and saying here’s a petition to lower your natural gas bill. Of course, a lot of consumers want to do that. They sign it. And lo and behold, a month or two down the line, that petition would have actually switched their service to Just Energy.”

Slamming can involve finding an employee of a company to sign over its energy contract without the top executives knowing it has happened.

In 2010, for instance, a Hampton Inn in downtown Manhattan was being sold to a new buyer. Just before the sale went through, and despite a stipulation forbidding any changes to the hotel’s service contracts, Just Energy got a member of the hotel’s staff to sign over a five-year energy contract to them worth $1-million and at rates 70% higher than offered by the local utility.

Yet the staffer worked on the hotel’s custodial staff and had no authorization to sign the contract. Months later, the new owners terminated the contract with Just Energy after they realized what had happened.

In total, there have been at least four lawsuits launched against Just Energy over allegations it is engaged in slamming – one in the U.S. and three in Canada.

The Canadian lawsuits included a 2008 action launched by Streamline Foods Ltd., a Belleville, Ont.-based food company, against Just Energy (which was settled), a 2011 lawsuit launched by the Canadian Medical Association (the lobby group for Canada’s medical doctors) – which was also settled – and a 2013 lawsuit initiated by D’Angelo Brands, a soft drink company owned by flamboyant Toronto businessman Frank D’Angelo, that’s still before the courts. Just Energy denies any wrongdoing in these cases.

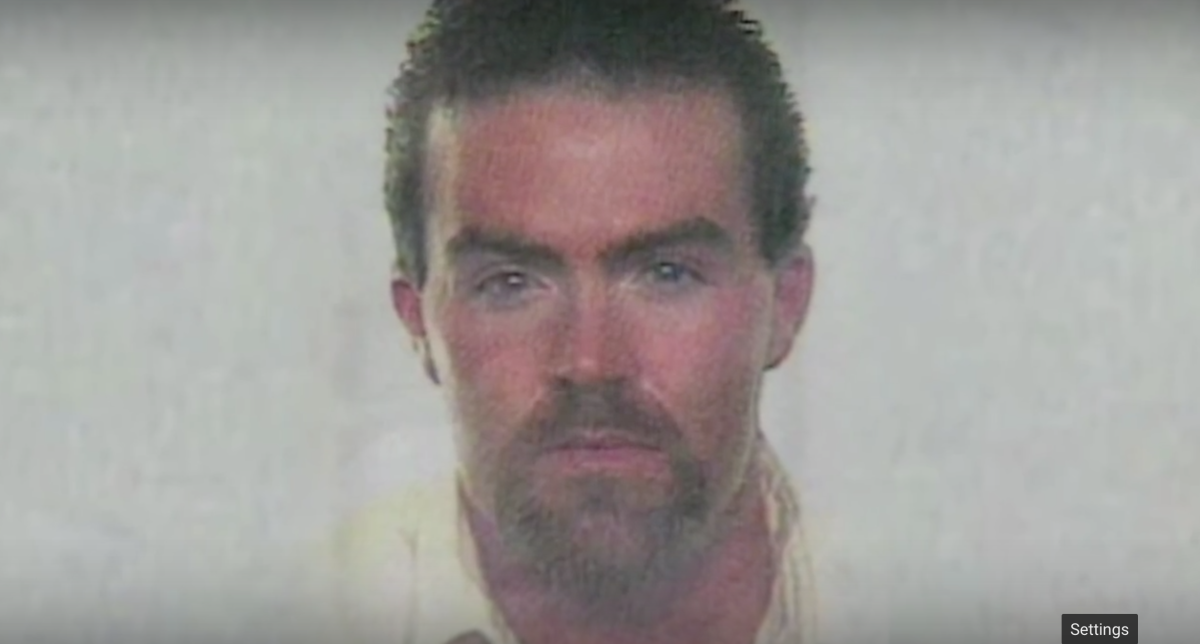

Glen Lancaster

All three of these lawsuits accused Glen Lancaster, a Just Energy salesperson who lives in Kingston, Ont., of being involved. Yet, in 2006, Lancaster received a three-year prison sentence for his role in a series of fraudulent companies. He’d worked with Guy Paul Beaupre, a notorious fraud artist whose stock-in-trade was telemarketing and other similar scams orchestrated during the 1990s (Beaupre went to prison in 2004 and was ordered to pay $2.7 million in restitution to his victims for his crimes).

Lancaster pled guilty to three fraud charges, with losses for victims in the order of $6 million. During his sentencing, the judge observed: “You could sell refrigerators to Eskimos. Your problem is not knowing when the Eskimos don’t want the refrigerators.”

Lancaster began working for Just Energy in 2005 after he’d already been publicly connected to Beaupre’s criminal enterprise. In fact, Lancaster was working for Just Energy when he went to prison, and commenced working for them once he got out. What’s more, he was working for them right up until this past winter.

“They hire a convicted fraudster,” says Toronto businessman Frank D’Angelo, who’s suing Just Energy over a slamming claim. “It's a little bizarre."

The adviser and the Russian mafia

Just Energy’s odd choice of employees does not end with Glen Lancaster. There was also Owen Mitchell, a key player in the YBM Magnex scandal of the late ‘90s. YBM was a magnet company that turned out to be a front for the Russian mafia, most likely designed to launder their ill-gotten profits through the capital markets.

Mitchell was an investor and director of YBM while also being a vice-president of First Marathon Securities Inc., YBM’s underwriter. He chaired a special committee that was set up by the company to investigate rumours the company had ties to organized crime – before the company was granted the right to raise capital.

Despite being told by the company’s private investigators that such links existed, Mitchell produced a report for the board that was later labeled a “whitewash” by one of the investigators. YBM went on to raise $100-million from investors and had a market capitalization of almost $1-billion before it was exposed as a massive fraud.

The Ontario Securities Commission charged Mitchell for failing to do proper disclosure before YBM submitted its prospectus, and in 2003 he was fined $250,000 and banned from sitting on the board of a public company for five years. Yet Rebecca MacDonald testified as a character witness on Mitchell’s behalf at the OSC hearings. And he went to work for her in 2001 in the middle of the YBM fallout, as a capital markets adviser. He got rich doing so before his sudden death last month at his home in Toronto.

Fines and penalties galore

In the end, Just Energy’s behavior has meant they’ve been hit with no shortage of fines and sanctions. In fact, in Illinois, complaints were so numerous that CUB tried to have Just Energy’s license pulled.

The Illinois state’s attorney office did sue one of the company’s subsidiaries for consumer fraud in 2008, which resulted in the company paying $1 million back to customers (part of that settlement involved Just Energy conducting an audit of its sales practices, which revealed the company had received 30,000 complaints in one year alone).

Ohio, New York and now Massachusetts have fined the company too, while the Ontario Energy Board has slapped Just Energy with a total of $570,000 in penalties since 2011. In Alberta three of the company’s salespeople pled guilty to charges relating to switching an energy supplier without customers’ consent, and were charged with forging signatures and impersonating customers on the phone.

The company has also been accused of manipulating its books. In 2012, Bay Street’s top two forensic accounting firms, Accountability Research Corp. and Veritas Investment Research, issued reports complaining about Just Energy using a non-GAAP, non-regulated method of reporting its financial statements.

They accused the company of using this method to exclude or obscure regular costs, such as marketing expenses, and thereby giving a healthier portrait of the company than was warranted. “Very basic expenses were not being counted by them,” says Al Rosen, ARC’s founder. “And therefore they showed this artificial profit.”

ARC even said the company was playing a “shell game” by overestimating the number of new customers it had signed up. Rosen accused Just Energy of using these unregulated accounting methods to trigger executive bonuses.

The ARC and Veritas reports spooked Bay Street. By then, the company was weighed down with nearly $1-billion in debt. When Just Energy put forward a prospectus to raise $1-billion in various unsecured debt securities, common shares and preferred shares three years ago, it failed.

“It was a dud,” says one bank-owned brokerage analyst. “No one else would give them money so that’s why they went to CPPIB.”

Indeed, Just Energy turned to the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, which lent them $105 million in unsecured notes with a 9.75 per cent coupon. To many, the nearly 10 per cent interest rate was an indicator CPPIB didn’t view the company as entirely “credit-worthy.”

CPPIB refuses to comment on why they made the investment in Just Energy or what is the current status of the loan – although some speculate that MacDonald’s ties to the federal Tories may have played a role.

Oliver unconcerned

Clearly, though, MacDonald’s track record as a corporate leader has not set off any alarm bells with Joe Oliver and CP Rail – whom seem content with their decisions with placing her in positions of influence. She herself refuses to grant media interviews and declined a request to comment for this article.

Oliver spokesperson Nicholas Bergamini responded by saying: “Our government consults widely with leading business and economic innovators – to hear ideas to create jobs, growth and long-term prosperity.”

And CP Rail spokesperson Marty Cej says that MacDonald has the “full confidence of the board” and that her posting to the head of its governance committee was an “unanimous” decision. When pressed if they conducted any due diligence on her background, Cej repeated the same statement.

For her critics, Just Energy is a company that consumers should avoid. As Rosen says: “It's something that you should run far and fast away from.”

Comments