Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

One single email among several hundred entered into evidence at the Duffy trial throws glaring Klieg lights onto the dynamics inside the PMO. It reveals Stephen Harper's inbred contempt for the rule of law, his own legal advisors, and even the Canadian constitution itself. And it sheds more light on the PM's disgraceful head-butting last summer of Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin.

For six days in February 2013, as the Duffy expense scandal careened out of control, PMO lawyer Ben Perrin and senior PMO and Senate staff wrestled to head off the possibility of a full-blown constitutional challenge to Duffy’s seat.

According to the Constitution Act, 1867, which is Canada's actual constitution, all appointed senators must a) own at least $4,000 in property in their home province, and b) live there. This, in February 2013, presented an obvious problem for Mike Duffy, a senator appointed for P.E.I. who in reality had lived in Ottawa for decades.

If Duffy didn’t declare the fiction that P.E.I. was his primary home and claim his Ottawa home as a secondary residence, his Senate eligibility was in jeopardy. But now that he'd made the claim, the PMO was ensnared in scandal. One that had to go away.

Whether Duffy zigged or he zagged, he was trapped by the reality that he really wasn't eligible to sit as the senator from P.E.I.

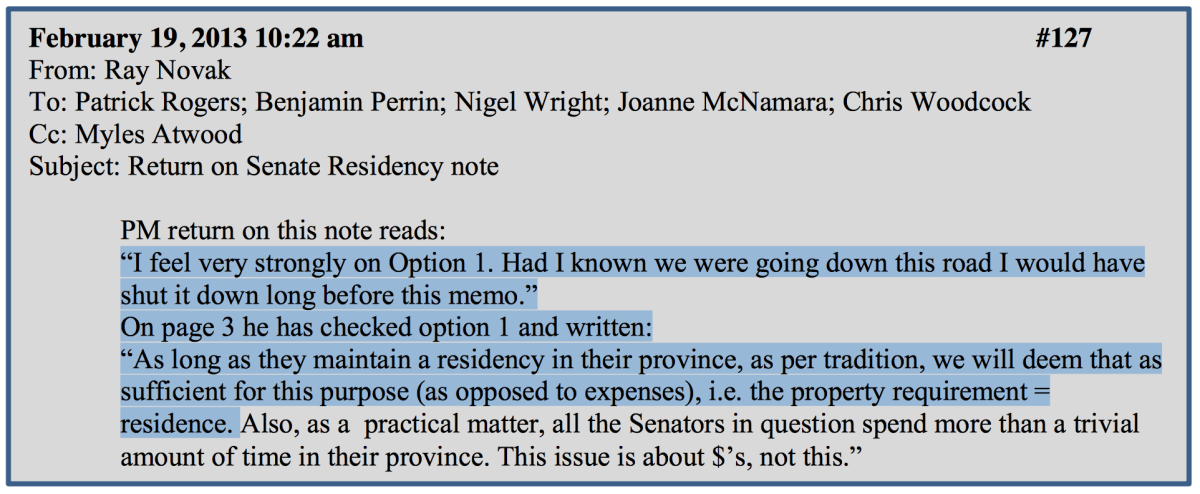

Solving this riddle was a problem the PMO team struggled to overcome. On February 18, they relayed proposed solutions to the PM regarding the anticipated eligibility problem. But the next morning, February 19, Harper unceremoniously nixed them, via this extraordinary email from his principal secretary, Ray Novak (now his chief of staff).

Clearly incensed that Perrin, Wright and the others had opened up the constitutional eligibility question, Harper set out a simple new test by fiat: property ownership equals residency. Full stop, problem solved.

Want to be a senator from Quebec? Get a time-share at Mont Tremblant

In other words, if you want to be a senator from Quebec and have a time-share at Mont Tremblant, you're good to go. In fact, a $4,000 stake in a cow-barn in Rimouski will do the trick.

Except the problem wasn’t solved. You couldn’t pass Constitutions for Dummies with an idea like that. Not even Stephen Harper can eliminate a constitutional requirement with the stroke of a pen.

Ben Perrin took no time at all destroying Harper’s residence theory in an email to Nigel Wright half an hour later. But he said nothing to the prime minister about it.

Indeed, what the emails show is that Stephen Harper — with zero legal training — dominated and intimidated his own PMO lawyer. Despite being a constitutional expert, Ben Perrin might as well have been the office errand-boy, for all the respect he appeared to garner inside the PMO.

In fact, nobody in the PMO pushed back on the prime minister’s constitutional illiteracy, which explains a lot about how Nigel Wright got boxed into an impossible position, and how things are going for the government over at the Supreme Court of Canada these days. Because these two things are intimately connected.

Indeed, as events progressed through the spring of 2013, the PMO asserted complete dominance over Senate functions, even to the point of dictating a committee report word for word. Only one person, Chris Montgomery, the Senate’s director of parliamentary affairs, stood his ground and defended the rule of law against unprecedented PMO interference.

But PMO staffers, oblivious to the most basic rudiments of constitutional democracy, were incredulous at Montgomery’s “epic” and “unbelievable” gall. Montgomery was the problem. By summer’s end, he had walked the plank, and Perrin was long gone, too.

Not team players.

Yet the Duffy expense scandal, far from being a one-off, signaled a far deeper malaise in the PMO’s relationship with the law.

Nadon case a replay of the Duffy mess

It took almost no time at all for Harper's constitutional hubris to erupt again, this time in even more spectacular fashion.

Marc Nadon’s doomed Supreme Court appointment was, by curious twist, a virtual instant replay of the Duffy mess. Just months after Harper accepted (or demanded) Nigel Wright’s resignation, he ran afoul of the Constitution Act yet again. In September 2013, Harper attempted another eligibility switcheroo, this time passing off a semi-retired Ontario-based Federal Court jurist as a Quebecer.

But there was a fly in the ointment. Back in July, 2013, just weeks after the Duffy scandal broke, Beverley McLachlin, as a routine function of her chief justice role, flagged a potential eligibility issue when she became aware that Federal Court candidates were being considered for the upcoming Supreme Court Quebec vacancy.

Just like Ben Perrin before her, McLachlin communicated her concerns over constitutional eligibility to the prime minister's chief of staff, who by this time was Ray Novak. And precisely as it had done mere months earlier, the PMO shrugged off the warning.

(Justice Minister Peter MacKay did take the step of obtaining a legal opinion about Nadon's eligibility, but asked the wrong question. Instead of asking whether a Federal Court judge was eligible for a Quebec supreme court appointment, the minister should have asked whether an eligibility challenge might possibly succeed.)

So when the whole thing blew up in the government’s face in the spring of 2014, as the Supreme Court ruled against Nadon’s eligibility, the prime minister lashed out at the chief justice. Exactly as he had lashed out against Mike Duffy and Nigel Wright.

It was all someone else’s fault. It wasn’t Harper’s uninformed dismissal of the warnings of constitutional experts, or his headstrong pursuit of political gain.

Just like 2013, when the prime minister was humiliated in the media, somebody had to pay.

And so the PMO launched a venomous media offensive against the chief justice, planting the deception that she’d attempted to lobby the prime minister against Nadon. Of course that was a fabrication.

Now that we understand how effortlessly the PMO dissembles, how carefully it calibrates “media lines" for maximum political advantage, it’s plain what was going on.

Harper's savaging of Chief Justice McLachlin calculated to subvert judicial independence

The ruthless savaging of McLachlin was deliberately calculated to undermine public confidence in the chief justice and, as an open letter from hundreds of lawyers and law professors put it, “subvert judicial independence." Ray Novak's and Stephen Harper’s fingerprints are all over this shameful episode.

One can scarcely escape the image of the PM lying awake at night, seething at McLachlin and his own Supreme Court judicial appointees. The one branch of government that will not come to heel.

The problem is in plain view in that February email.

This is a government that can’t colour inside the lines. Its cavalier disregard of fundamental Canadian constitutional principles is writ large over bill after bill and all its dealings with other branches of government. Judicial independence, like Senate independence, is anathema. The same could be said for the Constitution Act itself, and the Charter of Rights.

By temperament, Stephen Harper is master and commander, and the PMO his enforcer. This is a profound departure from the divisions of power between the executive, legislative and judicial branches of government as laid out in Canada's Constitution Act, 1867, but it is the outcome we were warned of by the Gomery Commission, which cautioned Canadians of the dangerous concentration of power within the PMO.

Yet one holdout remains: the judiciary.

Even with seven of his own appointees on the top bench, Harper can’t get the Supreme Court of Canada to submit to his will. It's telling that so many of the government’s losses are complete blow-outs, where Harper judicial appointees have joined unanimous rulings against the government on prostitution, supervised injection sites, Senate reform, sentencing, assisted suicide, and even the Harper's pet pariah, Omar Khadr.

In the prime minister's fertile imagination, the Supreme Court is an activist bench that refuses to bend to democratic authority. But look again at Harper's imperious message to his team in February, 2013, with its willful disregard of competent constitutional advice, and look at the record. It's all there.

Canada doesn’t have an activist court at war with the prime minister.

It has a prime minister who is at war with the law.

Comments