Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

An expensive remote Arctic facility, personally promoted by Prime Minister Stephen Harper as a "world-class” research station, is less about pure science, and almost entirely about pushing oil, gas and mining development in the rapidly melting north, says one of Canada’s top polar climate scientists.

"You couldn’t call this the ‘High Arctic Oil and Gas Development Centre’ because that of course would provoke national and international outrage," said professor Tom Duck, an atmospheric expert with Dalhousie University in Halifax, in an interview with the National Observer.

“They are trying to cloak what they are doing under the guise of science, which has much better optics.”

The two-story Canadian High Arctic Research Station (CHARS) and campus currently under construction in the remote and barren hamlet of Nunavut’s Cambridge Bay will cost taxpayers an initial sum of $142.4 million, and another $46.2 million to operate for the first six years.

It was promised to be "a world-class Arctic research station that will be on the cutting edge of Arctic issues, including environmental science and resource development,” in Harper's 2007 Throne Speech.

And last year, the prime minister journeyed to its barren construction site location to smile for cameras at the groundbreaking ceremony and to give the station high-level publicity via PMO press releases.

Arctic climate change —an industrial opportunity?

But behind the veneer of this research super station— and promotional photos showing Arctic botanists sniffing lichens— is its official science plan which says climate change is a huge opportunity for extractive industries.

"The reduction in sea ice, in particular, could extend oil and gas exploration, increase access to mineral wealth, and open up potential new ice-free shipping routes,” states the science and technology plan for 2014-2019.

CAPP and mining lobbies helped shape Arctic research station

In fact, the station's first priority, says the science plan, is to provide “baseline” environmental information called for by the oil, gas and mining lobbies.

"Companies accept the obligation to monitor project impacts as a fair condition of development,” the plan states.

"However, both the Mining Association of Canada and the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers [CAPP] have identified better baseline data for regulatory approvals and management as critical for resource development in the North.”

The plan laments how an iron mine was required by an environmental hearing to monitor the "land, air, water, people, animals, and birds” as part of 80 conditions to operate. CHARS will solve that industrial hassle by leading the "monitoring and assessing cumulative impacts in resource-rich regions in the North."

The Arctic is where 30 per cent of the world’s undiscovered natural gas and 13 per cent of its oil have yet to be drilled. CHARS planners see Canada's Arctic attracting $100 billion in resource development investment in the next 10 years.

'Real' climate science cut back

The station’s rise comes as other Canadian Arctic science programs, especially those relating to climate change, have been severely cut back. Canada's world-renowned PEARL observatory at Eureka near the North Pole was nearly shuttered by the Harper government in 2012.

Professor Duck is a co-founder of the organization that operates PEARL and has long said the cuts nearly “crippled” his life’s work up there.

“We know that climate change is an enormous problem,” he told the CBC, in the Fifth Estate documentary Silence of the Labs in 2014. “So if you want to get out your oil… you make sure the scientists aren’t causing any problems. If you want to make sure the scientists aren’t causing any problems, you take away all their funding.”

The federal government employees union — the Professional Institute of Public Service of Canada —estimates that by 2016, the number of federal science jobs cut by the Harper regime will reach 5,000 —a figure the federal government did not dispute for this story.

Harper's Arctic legacy

The CHARS facility will be up and running by 2017 in time for the 150th birthday of Canada. It will undoubtedly be Harper’s largest legacy footprint in the Arctic.

The office for Environment Minister Leona Aglukkaq responded to criticisms about CHARS's industrial purpose by saying "once completed, it will harness science, technology, and traditional knowledge to inform environmental stewardship and responsible development while improving the well-being of Northerners."

“The location of Cambridge Bay, in the High Arctic, provides the researchers with access to regular sealifts and was chosen after consulting a wide range of experts including representatives from several of Canada’s major research universities."

Controversially, as the National Observer reported in July, the construction contract to build the CHARS facility went to a joint venture with a company run by a Conservative Party director who ran Leona Aglukkaq's federal election campaigns. The station is being built in Aglukkaq's home riding.

Federal New Democrats see the project as a bad deal for taxpayers. "It’s a big facility. It’s paid by the taxpayer. And it’s made almost entirely to benefit the extractive industry,” said Dennis Bevington, NDP MP for the neighbouring riding of Northwest Territories.

Bevington adds that CHARS didn’t come from a carefully calibrating process of planning. “To me, the way this facility showed up was one of Stephen Harper’s grandiose ideas in one of his trips to the North,” he said.

Greenpeace tracks Arctic oil exploration closely, and says CHARS is not what the North needs.

"Scientific research in the Arctic should be directed to helping us better understand and respond to the climate crisis, not enabling those working to make the crisis even worse," said Greenpeace Arctic campaigner Alex Speers Roesch in Toronto.

Low oil prices have dampened Arctic oil exploration. But Imperial Oil, Imperial, ExxonMobil and BP are looking for oil in the Canada's Beauford Sea, and Norwegian firms want to do seismic testing for oil in Canada's eastern Arctic at Baffin Bay. Inuit in Clyde River challenged the National Energy Board's authority to allow the tests and lost, but hope to take their case to the Supreme Court.

The U.S. government also gave Shell approval in August to drill off Alaska's Arctic coast.

Massive change predicted in the Arctic

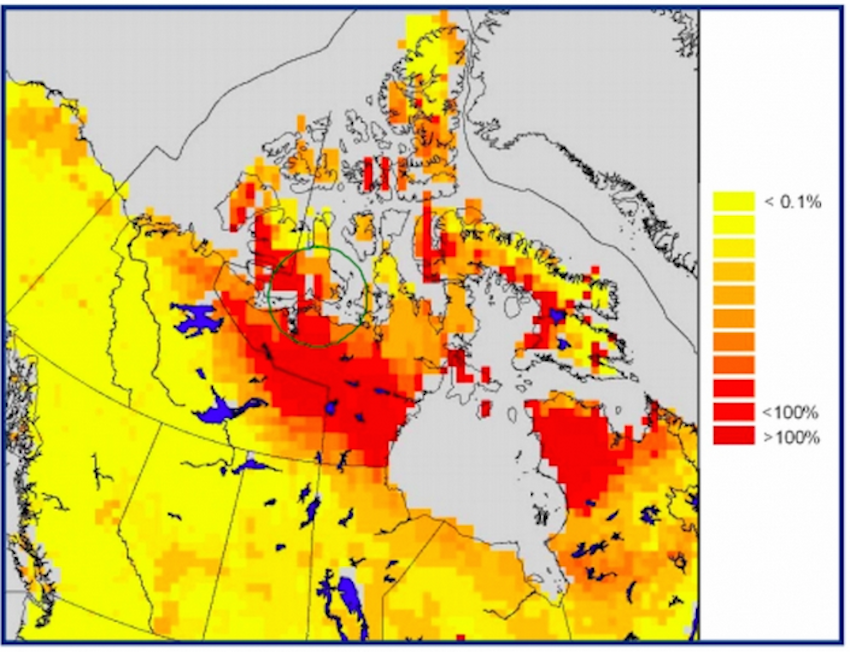

Government planners envisioned CHARS to be useful for some basic science. Its location in the predicted epicenter of an “incredible” turn over of mammals and birds due to climate-induced changes by the year 2100 was one reason the site was chosen. Environment Canada also said CHARS will "anchor" 46 research locations across the Arctic.

"Cambridge Bay is ideally located within a variety of ecoregions and in close proximity the Queen Maud Gulf Migratory Bird Sanctuary which is one of the world’s largest internationally important wetlands and contains the largest variety of geese of any nesting area in North America," said the ministry.

But Professor Duck says the far more scientifically interesting problems —Ellesmere Island's ice shelves or the North Pole's ozone depletion — are hundreds, if not a thousand-plus, kilometres away in the vast Arctic. However: “If you want to have a command and control centre for resource development and exploration, now it starts to make a lot of sense,” said Duck.

Liberals didn't respond to a request for comment. But the Green Party’s science critic —Burnaby North-Seymour candidate Lynne Quarmby —calls the station's fossil fuel agenda “appalling.”

Federal science shifted to industrial purposes

“The idea that we would invest research money to get more fossil fuel… to me that is fundamentally immoral,” said Quarmby, who is also a Simon Fraser University biochemist. "We know fossil fuels are a major contributor to climate change. We know around the world there is already tremendous human suffering and environmental damage. We need to transition off fossil fuels as soon as possible."

She adds that two of the country's largest science-funding bodies —the National Research Council and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) —have become a “concierge for industry,” where scientists often need an industry partner to get funding.

Meanwhile, high above the Arctic Circle, the PEARL lab continues to limp along on a reduced budget of one million per year, and Duck no longer works there. But before PEARL encountered funding difficulties, Duck helped investigate the first Arctic ozone hole —a globally important finding with implications for everything from skin cancer to agricultural productivity.

Duck says since 1971 the Canadian Arctic has been warming four times faster than the global average.

Comments