A furry fiasco

Does Canada need tighter labelling laws for fur?

In October, National Observer received a tip that Canadian clothing retailer Kit and Ace was selling toques made with fur from a species of Asian dog. Here's what our investigation found.

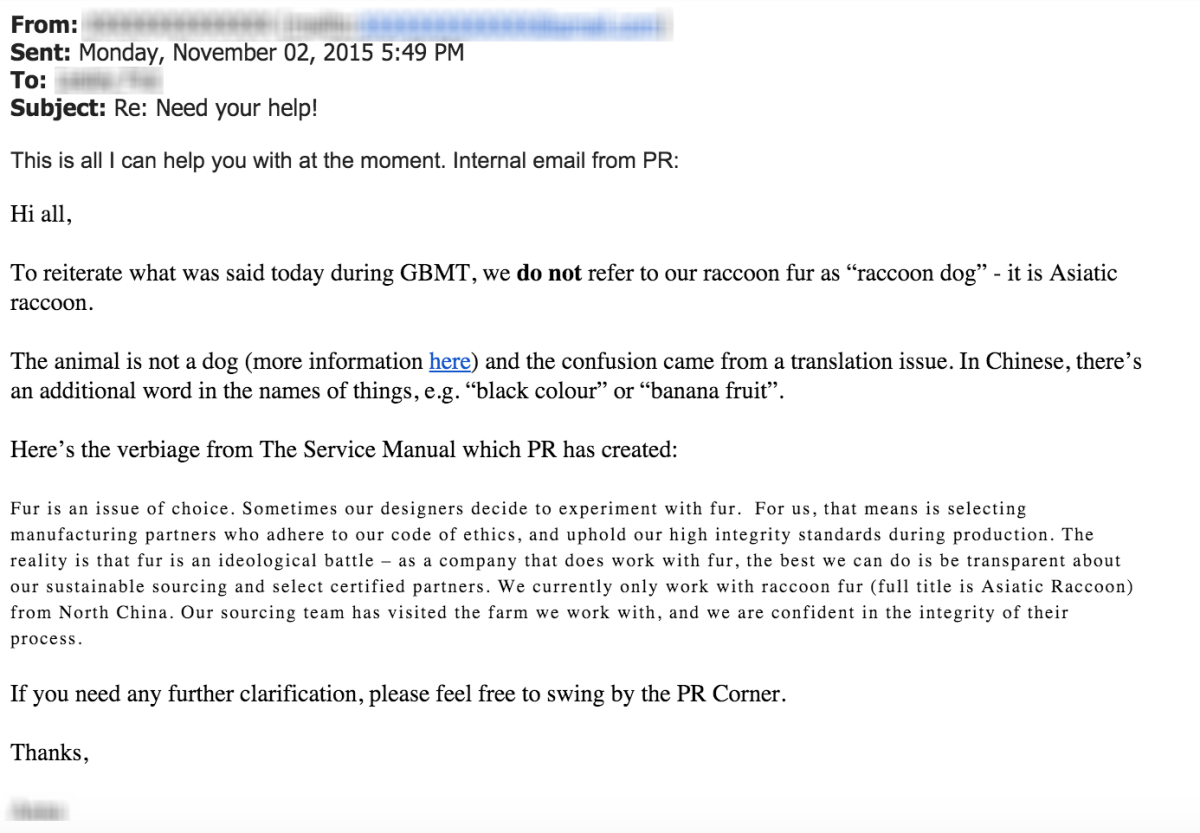

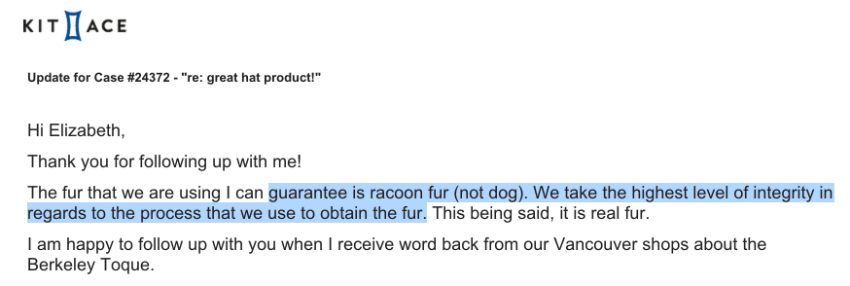

“I can guarantee it’s raccoon fur (not dog),” reads an email from a Kit and Ace customer service agent. The statement is in response to an inquiry about the Canadian retailer’s new Berkeley toque, which has a fur pompom labelled "100 per cent real Asiatic raccoon.”

“It is raccoon fur,” reads another email from a different Kit and Ace agent in response to the same query. In both cases, the agents believed they were addressing customers, rather than a National Observer reporter.

A quick look online however, reveals that ‘Asiatic raccoon’ is the fur industry’s name for the raccoon dog (pictured right), a member of the canine family that resembles a raccoon, but is not genetically related.

Selling raccoon dog fur isn’t illegal in Canada, nor is its label, Asiatic raccoon. But it's a problem, scientists say, when customers are told the fur is from a raccoon — as the animal is actually a type of canine.

Unlike most other Western countries, Canada’s labelling laws make disclosure of the presence of fur—as well as its type and its country of origin— completely up to the discretion of retailers on most apparel including many coats, trims, hats, and other accessories.

For the fashion industry, being open and honest about their products, including fur, is a matter of integrity — a virtue Kit and Ace claims as a foundation of their business.

While the company did label the Berkeley toque as fur, an email leaked by a Kit and Ace whistleblower reveals misleading instructions to staff about the raccoon dog, its name and family classification.

Inside Kit and Ace

In early November, a National Observer reporter — posing as a customer — went shopping at Kit and Ace’s flagship store in Vancouver, B.C. Holding the Berkeley toque, she asked a staff member what ‘Asiatic raccoon’ was.

“It’s a raccoon from the Asiatic region… probably Southeast Asia,” said the saleswoman, smiling next to a display of the blue and grey hats.

She admitted she had not yet “been briefed” on the new winter toque, but promised that Kit and Ace works very hard to make sure all of its products, including fur, are “ethically sourced.”

Kit and Ace is a Canadian luxury apparel company founded in 2014 with locations across Canada, the United States, England, and Australia. On its website, it brands itself as “committed to integrity,” and defines integrity as:

“Doing what you say you will do, when you say you will do it. Doing what you know to be truthful. Doing what you know will make a difference. Taking a stand for what you believe in.”

Despite this statement however, a leaked email reveals an apparent attempt to silence staff concerns about the use of raccoon dog fur in Kit and Ace products, and to keep customers in the dark about the animal’s membership to the canine family.

The email was forwarded from a concerned whistleblower to a Vancouver-based environmental group called the Association for the Protection of Fur-Bearing Animals (APFA), which passed it on to National Observer.

Two months after the email was sent, a reporter once again posed as a customer and inquired about the toque via email. The responses — in accordance with the new public relations strategy — identified the fur as ‘raccoon’ only and referenced Kit and Ace’s policy of integrity:

The raccoon dog controversy

White raccoon dog. Photo by Tambako the Jaguar, Creative Commons.

The raccoon dog has been at the heart of the fur-labelling controversy in Canada for years.

Animal activists have long criticized the industry over its designation as ‘Asiatic raccoon’ on garment tags, claiming that it misleads Canadian consumers.

The raccoon dog, Nyctereutes procyonoides, is part of the Canidae family, which also includes wolves, foxes, coyotes, and domestic dogs. The stubby-legged animal is indigenous to East Asia and typically imported from farms in China or Finland under the names murmansky fur, Finn raccoon, or Asiatic raccoon.

All are inaccurate and misleading, according to retired University of British Columbia geneticist David Steele, who confirmed to National Observer that the raccoon dog has no relation to raccoons whatsoever.

“Label it as a canid. It’s part of the dog family. It’s not a raccoon. It has a look similar to raccoons, that’s all it is.”

When it comes to the fur industry however, the more accurate term ‘dog’ carries with it an incredible amount of stigma.

In 2014 the U.S. Federal Trade Commission made ‘Asiatic raccoon’ the exclusive, mandatory label for raccoon dog fur in America.

The decision came in spite of a prior U.S. Humane Society petition to ban the fur entirely, and a 2013 CBS news report quoted the Humane Society's "fur free" campaign head of research, Pierre Grzybowski:

"We urge retailers to drop all fur products, but that being said the treatment of raccoon dogs in China is the worst we have ever seen, including live skinning. At the same time, it's the most frequently misrepresented animal sold by the fur trade in the United States, whether as faux fur or a real animal."

Unlike many Western countries, Canada only bans the import of endangered species, a category that doesn’t include many types of dogs and cats.

Raccoon dog fur is the most widely mislabelled fur in Canada according to a 2012 report by the Toronto Star, which has reported extensively on how cat and dog fur makes its way into the country.

A further report by the Toronto Star noted that China is a major exporter of feline and canine fur, a by-product of the 2 million cats and dogs slaughtered in the country for food each year— and that 60 per cent of all fur clothing imported into Canada comes from China.

Canada's loose labelling laws

There is no law in Canada requiring retailers to label fur as long as it’s attached to the skin of the animal.

According to the Textile Labelling Act, only fur removed from the hide — wool woven into a sweater for example — must be disclosed, which means the fashion industry has no legal obligation to distinguish real fur, fake fur, fur type or origin on almost all coats, cuffs, hoods, trims, and accessories.

“In the Canadian marketplace, how do people get away with that?” asked Lesley Fox, executive director of the Association for the Protection of Fur-Bearing Animals (APFA) which has supported a handful of private member’s bills attempting to tighten Canada’s labelling laws.

None have been successful so far, and Canada remains unique in its loose requirements when compared to countries like the U.S. and Switzerland, which require that all fur products be labelled by animal and country of origin. Switzerland even requires disclosure of how the fur was obtained — whether the animal was farm-raised, trapped, hunted, or herded.

“I think in this day in age it just makes sense,” said Fox. “People want to know what they’re buying and we see that a lot with GMOs and food labelling.”

Fur is an $800-million industry in Canada employing more than 60,000 people, and according to the Fur Council of Canada (FCC), which represents its stakeholders, Canadian labelling laws have always been sufficient up until now.

When most fur in Canada was still being sold in traditional stores by furriers, there was no need to impose mandatory labelling, explained FCC executive vice-president Alan Herscovici.

“Fur stores in my experience, always say what type of fur it is. That’s their business and trade, and they always do,” he said. “But now the situation is changing.”

Today, more than half of all fur garments that enter Canada come through China, and in 2013, furskin imports spiked by 45 per cent — a total of more than $300 million.

This means all kinds of fur — properly labelled, mislabelled, or sometimes not labelled at all — makes its way into Canadian stores and into the hands of unwitting customers.

“Maybe the time is coming that [retailers] should put the proper name,” said Herscovici. “They may not always know fur products so well.”

He doesn’t argue with basic labelling logic: if Canadians have a right to know the ingredients of their food, they have a right to know the ‘ingredients’ of their clothes. But he said using the raccoon dog as an example is missing the point of the debate.

“It’s really red herrings generally,” he said. "They’re used as weapons in a battle where some feel we shouldn’t use fur. That’s what they really are.”

Animal-welfare advocates, however, strongly disagree.

The trouble with industry ‘integrity’

More than 6,000 mink were released by animal activists at this farm in St. Marys, Ont. in July 2015. Photo by Canadian Press.

Nearly 7,000 products are certified as ‘fair trade’ in Canada.

When FairTrade Canada’s green and blue symbol appears on a bag of sugar or a soccer ball, consumers know the item meets a strict set of social, environment, and economic standards. The certification is similar to that used for ‘organic’ produce and ‘certified local sustainable’ food.

When it comes to Canadian fashion however, no one is policing companies who claim to have ‘ethically sourced’ apparel or ‘integrity’ in their products.

A lack of fashion ethics infrastructure

“The ethics behind apparel has been a problem for years,” said Kemp Edwards, CEO of Ethical Profiling, a corporate social responsibility consultant that helps companies custom-source and manufacture sustainable products.

“People are trying to capitalize on the ‘ethical consumer’ without going the full distance to say, ‘We are socially auditing our manufacturing chain.’”

In the case of Kit and Ace, the company's claim that its northern China raccoon dog farm upholds its “high integrity standards during production” is a little hard to believe, he said.

“It’s laughable in my opinion. I think people who are using fur need to first determine and be quite transparent about what it means to ethically source fur.”

When the Kit and Ace whistleblower reached out to APFA about raccoon dog fur on the Berkeley toque, she had similar concerns, but would not consent to an interview or identification in order to protect her job. Lesley Fox, executive director for the organization, issued the following statement reflecting the employee's apprehension:

“I am alarmed by the jargon Kit and Ace is providing to their employees, who in turn spew this nonsense to their customers. Claiming to be confident in ‘the integrity of the process’ on a fur farm in China, a country that has no animal welfare legislation, is very concerning.

What standards of animal care and husbandry could they be possibly referencing? They also claim in their internal email that ‘the best we can do is be transparent about our sustainable sourcing and select certified partner’ – I would love to call them out on that.

I would be keen to know where the fur farm is in China that they source their fur from, and for them to post photos and videos of this farm on their website and social media feed. To be fully transparent about fur and fur trim is to be fully transparent about animal suffering. And as soon as consumers see those videos and photos of raccoon dogs trapped in tiny wire cages, they will leave in droves. So much for “integrity.”

No response from Kit and Ace

Kit and Ace would not respond to repeated interview requests from National Observer inquiring about the customer service agents who told a reporter that the hat was made strictly from raccoon.

Kit and Ace has also halted contact with APFA and Fox.

“It really is frustrating because it does leave consumers in the lurch and it manipulates employees,” said Fox.

“I think 'green-washing' is a really good word for it — how people manipulate names [like Asiatic raccoon] and use fancy codes and ethics. What codes? What ethics? It’s just the industry and us; there’s no third party.”

At a minimum, she said the fur and fashion industries should co-ordinate so that staff are better informed about their fur products, and able to effectively communicate their origins with customers.

Pro and anti-fur ethics aside, she added that it’s time for Canada to step up to the plate and tell consumers what they’re buying. If corporate 'integrity' policies won't do the job, then national labelling laws will need to be more explicit.