Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

A grave intelligence failure marked multiple catastrophic terrorist attacks in recent weeks in Egypt, Beirut and Paris. Brussels is in lockdown, braced for a Paris-style attack, while a firestorm of controversy blazes over social media's encrypted instant messaging apps. And a Canadian technology company is caught in the crossfire.

Whether those responsible for the ISIS attacks actually used communication by untrackable encrypted instant messaging remains unclear. We know that at least some in Paris didn't. Data on a discarded cell-phone found in a trash-bin outside the Bataclan led authorities directly to the safe-house where attack leader Abdelhamid Abaaoud met his doom.

Oddly, supporters of blanket encryption apps consider this evidence in their favour, when it actually points to the opposite conclusion. Had the attackers encrypted all their communications, per standard ISIS instructions, Abaaoud and his co-conspirators would still be at large instead of chilling at the morgue.

ISIS won't make that mistake again.

Encryption robs investigators of indispensable wiretap powers

Encryption technology is now so powerful that it can't be unlocked even by the host under court order, and is freely available on a number of smartphone apps that all the kids use. Messenger platforms such as WhatsApp, Snapchat, and Telegram sprouted up following the well-worn Facebook path of making their owners rich by designing hook-up apps.

The thing is, these apps also inadvertently immunize malicious users like ISIS and child predators from lawful investigation. Authorities have now been robbed of indispensable wiretap powers that they've possessed since the invention of the telephone.

That's not a good thing, because we have nothing to replace it. There's simply no investigative substitute for the ability to intercept extremist communications in real-time as attacks are planned. Increasingly, authorities are seeing subjects "go dark," meaning they've accessed encryption messaging software and their communications can no longer be tracked.

What authorities seek is that encrypted messaging apps code in a "key" that allows police (operating under warrant) to intercept communications and track militant extremists and terrorists in a manner similar to tapping a phone.

If we don't master this, we'll turn police into 19th century London bobbies, while ISIS roams the Internet virtually at will.

Kik: the Canadian connection

Terrorists also love Kik, Canada's sparkling billion-dollar messaging baby incubated at the University of Waterloo that boasts over 240 million users worldwide. The FBI has identified Kik as among the Internet's top jihadi social media recruiting and fundraising tools, although no evidence ties it to recent attacks.

In one now depressingly familiar example, three American teenagers, two brothers and a sister aged 16 to 19, were recently caught by the FBI at O'Hare International Airport in Chicago attempting to travel to Syria via Turkey, after being radicalized and groomed on Twitter and Kik.

Pictured below, another recruit coming to join ISIS in Syria through Turkey seeks border crossing advice, providing his Kik handle for direct, encrypted messages.

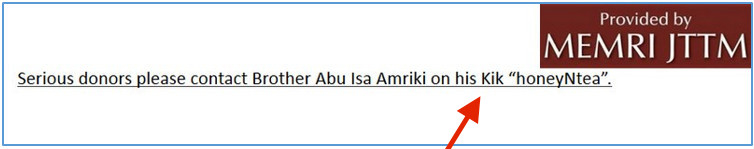

And less than a month ago, an enterprising reporter for the Mail on Sunday set up a sting operation and captured ISIS in the act, using Kik to coordinate a donation pick-up. Below, another ISIS Twitter account solicits donations through Kik. (All images care of MEMRI.org, altered for emphasis by National Observer).

Kik's special offering goes beyond encryption technology; designed to target teens without their own mobile account, and doesn't require registration to a cell-phone number. No registration is required beyond setting up a user name in a manner similar to an email account. The Middle East Media Research Institute reports,

Anyone can now communicate securely via an untraceable throwaway smartphone, purchased online, including on Amazon. Installing an encrypted messaging app such as Kik... takes a few moments, and after that, chatting securely and secretly with an Islamic State (ISIS) fighter... is one click away.

Reached for comment on the above, Kik media representative Rod McLeod said that Kik cooperates with law enforcement, and is able to assist authorities identify the most recent location of a specific user. Further, Kik will de-activate accounts when appropriate.

Disagreeing that the username model creates a system vulnerability, Mcleod said "A lot of people look at that as kind of a bad feature, especially law enforcement, but we’ve received a lot of feedback saying that having a username instead of giving a phone number makes you feel safer."

Especially if you're a terrorist.

McLeod says the app's vulnerability to terrorists affects all the social media apps that offer encrypted communications. This, however, seems to be the "everyone else is doing it" defence. How useful the law enforcement cooperation can be if users can't be identified and messages aren't stored is doubtful.

The problem with the Internet's get-rich-quick world is that, like Kik, Google and Facebook, social media apps are generally created by young middle-class "geeks" with no real-world experience of threat or insecurity. Kik's market differentiator makes it a perfect design for unlawful uses, like terrorism.

Putting it bluntly, in terms of safety and security, most software designers are wet-behind-the ears amateurs. As McLeod said of Kik founder Ted Livingston and the Waterloo cohort,

"Kik is kind of built in a way where the people that built the technology and the people that founded it—they wouldn’t want people to be able to read their messages so that’s one of the reasons why messages are encrypted and they aren’t stored on our servers."

And so a new ISIS weapon was born.

Organized psychopaths have weaponized social media designed for teenagers

In something as powerful as Internet software, security should never be the afterthought it almost invariably is. Rather, it should be built into the design protocol from the get-go. Organized psychopaths so easily co-opted and weaponized a social media industry designed for teens and gamers, it was like stealing candy from a baby.

Speaking of babies, how come you can't sell a crib in this country without proving it's safe, but you can build a secure end-to-end encryption system that lets ISIS jihadists chat with teens in their rooms, easy-peasy?

In ISIS we face an entirely new kind of foe and this is a new kind of war. Violent conflict could be transformed as radically as military aviation revolutionized war in the 20th century.

If that sounds like an exaggeration, picture ISIS drones.

So now, after way too many horses have left the barn, we're finally having the civil rights debate over encryption we should have had years ago in calmer times. Because in this debate, we can finally confront the intractable inner contradictions underpinning the foundations of the Internet itself.

In the founding utopian myth of the Internet, cyberspace is the New World dream made manifest at last; its constitution a Declaration of Independence from nasty earthbound laws and regulatory tentacles.

But cyberspace isn't an imaginary Neverland (where boys never have to grow up). It's right here, in the room where you're reading this. It's in Brussels, Paris, Beirut and Cairo. It's on your bus and in your car and your children's classrooms and bedrooms. It dominates your life.

And those nasty laws and regulations? They brought us safe cars and planes, safe medicine, buildings and food. It's called the rule of law, and it's the bedrock of modern civilization.

Should anyone—whether it's the police, Apple, Snapchat, Kik, or ISIS—be above the law just because they're on-line?

That's the Internet's kryptonite question.

Make no mistake: what's shaping up is a titanic power struggle between the state and the technology sector, now the world's largest and most powerful industry.

Tim Cook rights talk hews absolutist line close to the NRA

“Like many of you,” Apple CEO Tim Cook told an industry audience last summer, "we at Apple reject the idea that our customers should have to make tradeoffs between privacy and security. We can, and we must provide both in equal measure. We believe that people have a fundamental right to privacy. The American people demand it, the constitution demands it and morality demands it.”

Yet for all Cook's rhetoric about privacy rights, his absolutism hews much closer to the NRA than to Thomas Jefferson. And it was no coincidence that he mentioned customers first.

In a free and democratic society, no rights are absolute. All are circumscribed by reasonable limitations in the interests of the greater good. Determining the delicate balance in protecting both belongs to the judiciary, not corporate CEOs.

Of course, the spectre hovering over all the sound and fury is the off-stage presence of Edward Snowden. Almost to a person (including the New York Times editorial board), opponents of government efforts to break encryption mistakenly equate it with mass surveillance and a police state.

NSA can't keep their hands off the data cookie jar

As Snowden heroically demonstrated at enormous personal risk and sacrifice, the NSA couldn't keep its hands off the data cookie jar.

By engaging in profoundly intrusive and arbitrary mass data collection, and then lying about it, U.S. authorities poisoned the debate and destroyed public trust. Every reasonable person is or should be suspicious of the NSA's ultimate aims.

Yet police access to encryption keys, granted under warrant based on reasonable and probable grounds, permitting targeted surveillance of suspected criminals is the very antithesis of indiscriminate warrantless mass surveillance.

Stripped of all the high-falutin' jargon, the argument against government access to encryption is really an argument for placing the tech sector, including all the starry-eyed youngsters coding next year's whiz-bang app, above the law.

In that bargain with the devil, the price will be paid in souls.

In this debate, the deep and undisclosed hypocrisy and conflict of interest of tech libertarians must not be ignored.

For all its present hyperventilation, it was the tech industry itself that created the security risk that now threatens us, and they got richer than kings doing it.

Tech industry has built a massive uncontrolled surveillance state of its own

Apple, Google, and Facebook, the biggest dogs in the tech yard, all offer encrypted messaging and have a combined value of almost $1.5 trillion dollars.

All of them purport to "protect" the public from government scrutiny, yet profit spectacularly from the market in highly invasive private information in the form of "meta-data." This information is sold to undisclosed data brokers for unknown uses—mainly marketing.

According to Marc Goodman, technology expert and author of Future Crimes, the private sector has constructed its own for-profit invisible surveillance state, which generates $156 billion a year in revenues, more than double the annual U.S. intelligence budget. Every site we visit, every page we click, they silently track us and sell us.

They track our facial recognition data, our children's facial data, our movements and location. Google even scans and monetizes email content, claiming in a recent lawsuit that “a person has no legitimate expectation of privacy in information he voluntarily turns over to third parties." Meaning Google.

If we're talking about warrantless mass surveillance, the NSA can't hold a candle to private enterprise.

Brussels in lockdown needs answers now

Brussels is at a standstill, while the world converges on Paris in a week.

The tech sector needs to climb down from its over-the-top sense of entitlement and step up. Something's seriously wrong when a business sector that indiscriminately hosts terrorist accounts lectures democratically elected leaders about public safety, then shovels its own cash to off-shore tax havens.

We've got a problem here and we've got to fix it fast. There's an urgent global imperative to solve this crisis and find a middle ground between a police state of mass surveillance and giving ISIS killers their own private communications network.

In fact we already have the solution. Like Dorothy's red shoes, we've always had it. It's called a wiretap warrant. Law enforcement has to be given the time-tested powers it needs to protect the public.

Give them the keys.

Comments