Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Globally influential climate activist Yeb Saño has just returned home to the Philippines disappointed, having recently trekked 1,500km from Rome to Paris only to see the COP21 climate change summit reach a spectacularly bad result last weekend, he says.

Saño and those in his multi-faith and environmental entourage —called the “People’s Pilgrimage" — had marched for two months across Europe, praying for a miracle.

They wanted greater protection for climate-ravaged poorer nations like his Pacific archipelago home. His long walk for climate action inspired marches and fasts around the planet, from Brooklyn to Toronto. But in his expert view, as his country's former chief climate negotiator, the Paris climate agreement failed to protect poor countries.

“We should guard our sense of jubilation,” he writes, post-Paris."The nations that agreed to this outcome cannot take sanctuary under a diplomatic resolution that risks trivializing the suffering of the world’s poorest and most vulnerable."

The National Observer caught up with Saño near the end of COP21. The 41-year-old first rocketed to worldwide attention at an earlier COP climate summit in Warsaw in 2013.

Typhoon Haiyan—the strongest recorded tropical cyclone ever to make landfall —had just slammed into his nation. Ten thousand were killed instantly with an almost biblical storm, leaving many children orphaned. On behalf of his country, he tearfully told the U.N. plenary two years ago:

“I struggle to find words for the images that we see on the news coverage."

“I struggle to find the words to describe how I feel about the losses. Up to this hour, I agonize, waiting for word of the fate of my very own relatives.”

"I speak for the countless people who will no longer be able to speak for themselves after perishing in the storm."

Saño soon became known globally as the man who cried in Warsaw.

He went on an immediate hunger strike to urge greater ambition in the climate talks. The Canadian Harper government didn’t appear to help. It won the ‘Lifetime Unachievement‘ Fossil award that year.

"In just a matter of minutes —all of them died."

News eventually trickled in at that summit that the super storm destroyed his ancestral house in Tacloban. But by the grace of God, he says, his brother survived. But a "handful" of his friends did not.

"My brother lost his best friend. His best friend’s wife. His best friend’s young boy. His best friend’s mother. And his best friend’s father. All three generations —in just a matter of minutes —all of them died.”

Unlike Canada, where global warming may seem an abstract threat, requiring one less layer of winter clothing for some, extreme weather and storms are ripping poor countries like his apart, he says.

So after Warsaw, he quit his job as a climate negotiator, and embarked on a global journey to speak for the poor and voiceless facing climate effects. He's traveled to India and Australia, looking for clean energy solutions too.

Rome to Paris pilgrimage begins

But his biggest action yet was this year. On foot, Saño departed Rome on Sept. 30 with an entourage of multi-faith pilgrims. Greenpeace was in their midst too. Many wore shirts that read: “Hear the cry of the Earth, hear the cry of the poor.” Lutherans, Muslims, Jews, Hindus, Sikhs and Indigenous, and people from eight different countries, were among his following.

By November, they crossed the Alps, giving talks in small towns and places of worship along the way. The 1,500 km trek hurt Saño’s legs, joints and feet. But he, his brother and others kept going.

“That’s the miracle of the journey. Every evening, before we retired to bed, we are just painful all over," he says. "You think the next day will be a nightmare, just walking with the pain all over your body. Every morning… it just amazes us to no end that we are even able to stand up. Then when we start walking, we feel no pain.”Saño is a Catholic, and was inspired by Pope Francis’ climate speeches to the U.S. Congress and the United Nations General Assembly this year. He sees connections between his pain, his mission, and the suffering of his saviour.

“When we reflect on the life of Christ and how he had to suffer in order to save the world, our journey has a lot of parallels with his life, including being with the ordinary people, and convincing others to be part of this struggle.”

“Also carrying our own cross, carrying our own suffering in order to translate that suffering into courage. I call it activism, in being able to speak for others who can’t speak for themselves. That’s one of the main themes of our journey — carrying the memory of our friends who died in the typhoon.”

Avarice, arrogance and apathy

Saño says the climate crisis is a deeply moral problem, stemming from three things. Interestingly, he says, they all begin with the letter "A" whether spoken in English, Italian or French.

"The first is avarice, which is extreme greed," he says. "The second thing is arrogance, which is a exaggerated sense of one’s importance. The third is apathy, or the belief that someone else will save the world.”

By mid-November, Saño’s march entered Switzerland then France. He was then just 300 km from Paris when tragedy struck.

Islamic State terrorists claimed responsibility for murdering 130 people in the French capital with six coordinated suicide bombings and shootings. The first hit the Stade de France soccer stadium in Paris's northern Paris suburb of St. Denis — just a train stop from the COP21 climate summit, which would soon receive 147 world leaders. France declared a state of emergency, and closed off borders.

"We were really worried if we would be able to complete the journey with a lot of security measures," Saño recalled. "Martial law was declared, and no actions in the street [were permitted] —not even a group of people could walk into Paris. So we had to split up into smaller groups, and walk into Paris silently.”

The separation from his friends was discouraging after such a long walk. But when he arrived at Saint Mary’s Basilica in France's capital, he was surprised to see hundreds of pilgrims from all over Europe converging.

"There was singing, celebration, speeches, food. It was an amazing celebration of all the journeys. The next day we were welcomed in a more formal way by the executive secretary of the UN climate convention," Saño says. "We turned over a petition with 1.8 million signatures calling or urgent action and ambition in the Paris talks.”

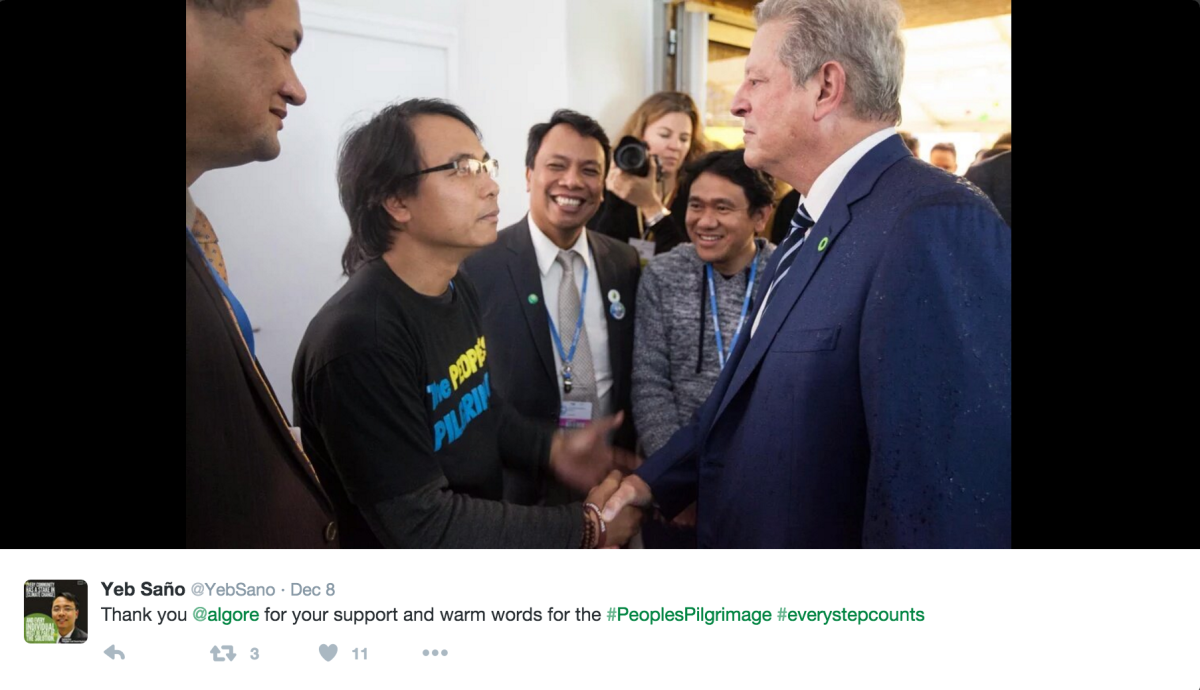

Saño was then greeted everywhere he went at the summit —by journalists, to well-wishers to Al Gore.

But in the days that followed, the skilled negotiator with an eye for legal detail quickly saw his hopes for COP21 die.

"The word 'commitment' does not appear on the Paris Agreement," he wrote. "This is so because the most powerful nations on earth, developed and developing alike, refused to use this word in order to achieve a political compromise that would be expedient for governments.”

He says the Paris Agreement is even weaker than the 1992 Climate Change Convention and the 1997 Kyoto Protocol.

"What this agreement represents is the sheer avoidance of rich countries to be accountable for the climate crisis, and the acquiescence of others to the weakening of the climate regime — again gravely ignoring the importance of equity, fairness, adequacy and ambition.”

"The issue of 'loss and damage' was clearly a lost cause, when rich countries treated it with perfunctory interest," he says. "And was even further lost with the brutal qualifier that the issue 'does not involve or provide a basis for any liability or compensation.'”

Even the much lauded goal to "pursue efforts" to limit global temperature rise to 1.5°C —an action Canada supported —was mere "diplomatic sleight of hand,” he asserts, without the presence of words like "commitment" to back it up.

The People's Pilgrimage marches on

By summit’s end, Saño looked tired as he looked to his phone to figure out where to meet his friend in downtown Paris.

“It’s hard to be happy,” he sighed.

"What we see is that the text will not avert the climate crisis. It will not even keep global warming within safe levels. It’s a text with a bunch of words which are just a combination of false promises, political compromises, and just a very weak indication the seriousness with which countries should be looking at this problem,” he says.

Saño flew home to his two kids, aged eight and 11. He vows his climate pilgrimage will continue.

“Our collective message has been we cannot confront the climate crisis if we do not stand together as a human family."

Comments