Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

"I mean no disrespect when I say this, but here's my offer: I'll invest $1-million in Canadian energy companies if, out of grace and for the absolute good of Canada, the premier of Alberta resigns. She’s gotta go, she’s gotta go... I wouldn't touch them now, because she doesn't know what she's doing... Please step down, please. Do it for the sake of Canadians.” - Kevin O'Leary on Toronto radio station NEWSTALK 1010, January 11.

When business TV personality Kevin O’Leary – one of the stars of the ABC hit show Shark Tank – made these comments last month, they triggered a mini-media squall, ratcheted up when he said he was considering running for the leadership of the federal Tory party.

If O’Leary was not jesting about investing in Alberta’s beleaguered oil patch – now reeling from crude falling to about $30 a barrel – should it accept his money? After all, one of the less well-publicized charges leveled against O’Leary is that he once helped destroy an entire industry.

In this case it was the educational software sector of the 1990s and early 2000s.

Back in those days, O’Leary was president of the world’s second-largest consumer software company, The Learning Company (TLC) Inc., before he helped sell it to Mattel, Inc. in 1999 for (US) $3.6-billion – where it immediately crashed and burned, devastating this once-flourishing business. “It killed the educational software industry,” says Bernard Stolar, a legendary figure in the video game industry with leadership roles at Atari, Sony and Sega before Mattel hired him to try and rescue TLC after O’Leary was fired. “It basically killed it. It killed it because there was so much product out there and all of the product was crap.”

Doug Carlston, co-founder and former CEO of Brøderbund Software Inc., a major, San Rafael, CA-based educational software and gaming company during the ‘80s and ‘90s, says the demise of TLC accelerated the collapse of the entire sector. “Most of the rest of the (educational software) industry went away,” he says, “pretty quickly.”

Charles Tyros, who worked at TLC as a reseller in Boston, MA, says there were more than 200 companies selling educational software products prior to TLC’s collapse. Afterwards, he says, “there were not many left after two or three years: there were very very few of those same companies.”

So how much was O’Leary and his controversial business methods responsible for the industry's collapse? And what does it say about his judgment if it's true?

O'Leary storms the educational software industry

For those people still producing educational software, Kevin O’Leary remains an unpopular figure. “In a world such as Kevin O’Leary plays in, it’s all about buy and sell,” says Art Willer, president of Bytes of Learning Inc., an educational software company based in Fort Erie, Ont. "Buy something and sell it for another dollar and I've made money. It's not about 'Did I actually contribute something or build something in the process?'. It's only about my bank account."

In telling his origin story, O’Leary points to founding and running SoftKey Software Products Inc. as one of his proudest business achievements. With help from $10,000 borrowed from his mother, he operated SoftKey out of the basement of his Toronto home in the early ‘80s, selling business and office productivity software. Eventually he moved the company to Boston.

Although the company grew, it struggled and by the early ‘90s was losing money. By then O’Leary had noticed the burgeoning field of educational software, which had emerged in the 1980s, wedding computer technology with teaching math, reading, geography and other subjects to children. O’Leary steered SoftKey towards this sector.

One of the pioneers in educational software industry was Ann McCormick, who co-founded The Learning Company (TLC) in California in the early ‘80s, helping create groundbreaking products like Reader Rabbit, which eventually sold 14 million copies. “My games were for fun and kids liked them,” recalls McCormick. “We had $1-million in sales our first year.”

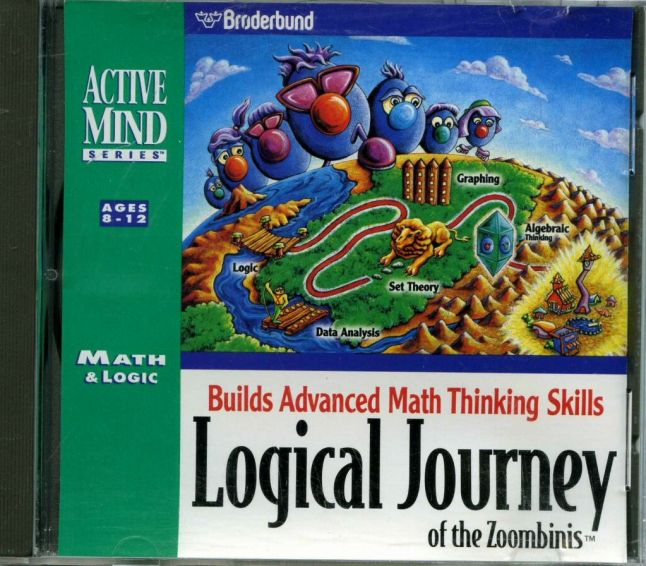

In fact, driven by the boom in personal computers, by the mid-‘90s, dozens of educational software companies were selling titles such as The Logical Journey of the Zoombinis, Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? and The Oregon Trail to parents and school boards. Many of these outfits were established by people who had educational backgrounds – such as Art Willer, who worked at Toronto’s board of education before founding Bytes at Learning in 1984. “(The market) took off through the 1990s because computers became more capable with graphics, audio, and multimedia," he explains. "Creative people and investors alike saw a great opportunity."

But producing good educational software meant spending money on research and development and hiring artists and computer animators. Michelle Bushneff, who worked at Brøderbund as a vice-president and creative director, recalls that the corporate environment was loose, pleasant and dynamic. “It was a super amazing place with super amazing people that cared about the quality of the products,” she remarks.

But to pay for that kind of overhead and talent meant pricing software at a premium – at least $40 per CD-ROM and often much more. And as computers grew faster with better graphics, companies had to keep abreast with dramatic-looking software. “The costs were just unreal,” says Brøderbund’s former CEO, Doug Carlston. “They were beginning to climb up to the cost of making movies. They were in that range.”

What changed everything was when Kevin O’Leary’s SoftKey entered the industry with a different model. While many of the educational software companies sold through specialty outlets with runs of 100,000 units, SoftKey introduced the idea of selling millions of copies through big-box retailers like Walmart and Costco.

In his 2011 autobiography, “Cold Hard Truth”, O’Leary recalls arranging a meeting in the early ‘90s with Walmart after the retailing giant said they wanted to sell consumer software. Walmart is famous for forcing suppliers to cut their prices drastically. In this meeting, when the Walmart buyer learned that SoftKey products sold for $39.95 on average, he bluntly told O’Leary, “Here, y’all gonna sell your computer stuff for $19.99.”

O’Leary said this meeting led him to the conclusion that SoftKey had to sell its software at bargain-basement prices in order to boost sales. “The days of $79.99 software were over” he told employees at SoftKey.

In retrospect, this strategy was responsible for sowing the seeds of destruction for the entire educational software sector. “You couldn’t invest the kinds of (R&D) budgets and still sell the software for what you needed to sell them for to make any money,” explains Bushneff.

Indeed, in an interview last year with Gamasutra, a gaming industry magazine, Ken Goldstein, the former vice president of entertainment at Brøderbund, said when educational software began selling through big-box retailers, and companies were trying to hit volumes in the millions “the idea of a retail price point like $49.95 to $59.99 doesn’t work,” he told the magazine. “You need to sell at $29.95… Then competitive retail dropped to $19.95 and wholesale slipped to $12.”

But dropping prices meant lower profit margins. In fact, Softkey began selling CD-ROMs for as low as $9.95 thanks to mail-in rebates. That meant only $1-$2 profit margins on every individual copy, which undermined their ability to finance the cost of developing new software. “The new pricing model, driven by both Softkey and every other developer in the business selling CD-ROMs at such low prices, destroyed the economic viability of the… production cycle,” said Gamasutra.

Brøderbund’s Carlston recalls that Softkey was, in effect, often giving away their software. “Our best-selling product was called Print Shop,” he recalls. “They had a competing product called PrintMaster. They offered it for $29.95 and ours was selling for $59.95. (But) theirs were selling with a $30 rebate so basically they were selling it for free.”

In order to sell software so cheaply, O’Leary had to slash Softkey’s R&D budget, from 24 down to 11 percent of expenses. Carlston recalls that after Brøderbund was sold to O’Leary’s outfit in 1998, “they dropped our entire development team.” In fact, Brøderbund went from 1,700 employees at the time it was purchased – down to under 100 within a year, he says. O’Leary would also take old software, update the code a little, stick it in new boxes before selling it.

By not investing in product development in the rapidly evolving software market, many feel O’Leary doomed his companies. “Price-cutting and slashing R&D are never good for the long term,” says Willer. “In fact, those actions sell the long-term value of the company in return for short-term gains.” Willer remembers sitting across from O’Leary at an Ontario software developers’ conference. “He looked at me and said ‘Put it in a box and sell it’ and that essentially characterizes the approach I witnessed. I never knew SoftKey for producing anything worth buying. As O’Leary professed, it was a throw-it-in-a-box-and-sell-it strategy.”

O’Leary and his defenders have said that lowering the retail price of educational software meant it was now affordable to greater numbers of parents and schools. “Kevin, I think, was a visionary with commodification of the consumer channel to make software available for everybody – every Mom, every Dad, every child getting it in the schools,” says Scott Murray, SoftKey’s former CFO.

O'Leary goes on a buying binge — to disastrous result

The second controversial method O’Leary embraced was growing SoftKey by buying other software companies. In his book, O’Leary says it was a way of snatching up the latest products in the pipeline.

In total, SoftKey bought more than 20 companies, eventually acquiring industry leaders such as TLC, Minnesota Educational Computing Corp., Mindscape and Brøderbund, soon emerging as the second largest consumer software company in the world after Microsoft with 3,000 employees. Their product sold in 15,000 retail outlets in 47 companies and had sales of (US) $840-million by 1998 (and a net loss of US$105-million).

But this buying spree also raised concerns – that it was merely masking real financial problems. Experts who study this acquisition model say it’s risky because you incur high debt, or you purchase firms by issuing shares, which dilutes their value. “It’s not organic growth but acquired growth,” explains Alan Mak, a Toronto-based forensic accountant.

This became an issue in 1995 when SoftKey made a play for TLC. Other companies were wooing TLC too, notably Brøderbund. Doug Carlston, Brøderbund’s CEO, began looking at SoftKey’s methodology – and was unimpressed. “It’s pretty straightforward,” he relates. “You run pretty good quarter to quarter results and then you buy three companies and you take a huge loss and attribute it to goodwill write offs. And then you go right back to showing nice steady quarter to quarter gains. So most of time you’re showing good gains and then suddenly you drop hundreds of millions of dollars at a quarter as a result of acquisitions of three or four companies – which is very hard for people to untangle.”

But Carlston said that if you looked at the value of SoftKey’s shares over a longer period of time, “it’s going down pretty substantially.”

In fact, video gaming executive Bernard Stolar says no one was paying attention to whether real profits were being generated. “They were buying companies and didn’t give a shit about the bottom line,” he says. “Wall Street was looking at the top-line number (revenues) and was not looking at the bottom-line number… It’s almost like a Ponzi scheme.”

Another outfit that examined Softkey at that time was the Center for Financial Research and Analysis, Inc. (CFRA), a Rockville, MD-based forensic accounting firm. In a 1996 report on SoftKey, CFRA found numerous problems, including overstated earnings, excessive debt load, suspicious firing of its auditors, and conflicts of interest with people on its audit committee. CFRA’s report so alarmed TLC’s board that instead of agreeing to take SoftKey shares as a form of payment for TLC, they took cash instead, “because TLC was concerned about owning stock in SoftKey,” recalls Howard Schilit, CFRA’s former president.

With the (US) $606-million purchase of TLC in 1996, SoftKey took TLC’s name. And the new TLC, with O’Leary as its president, continued to gobble up competitors.

Two years later, good fortune rained down on O’Leary and his fellow TLC executives. It was the peak of the dot.com bubble and O’Leary was poised to take advantage of it. They had a suitor, too. Stolar believes this was always O’Leary’s end game. “(O’Leary) didn’t care about the reality of what was happening,” he argues. “He cared about focusing on building the company to sell it. End of story.”

Yet, by 1998, TLC was considered an emperor with no clothes by people such as Sean McGowan, one of Wall Street’s leading consumer brands analysts, most recently with Oppenheimer & Co. Inc., a New York-based investment bank. In an interview with this reporter in 2012, McGowan said that by the late ‘90s, TLC was “stripping out R&D expenses to puff up sales. A lot of their brands were getting old and tired. Their customer base denigrated to convenience stores and drugstores. It wasn’t like they were the best-selling product in the software channel. They had exhausted the expansion of the channel to the point where there was a lot of inventory out there that was not moving very well. And then on top of that are these stories that couldn’t be proven: that they were double booking and that their sales were not what they said they were.”

McGowan said that cutting R&D, which he called the “lifeblood” of the software industry, was also catching up to TLC. “So they’re milking (the old brands) and you can’t do that forever.”

The collapse of TLC and its fallout

TLC’s buyer was toy giant Mattel, Inc., maker of Barbie and Hot Wheels. Mattel was in big trouble and was betting that leaping into the world of educational software would revive its fortunes.

Mattel’s timing was horrible: the industry was facing a looming threat, namely from the Internet. As Carlston says: “(Customers) were changing their attention from buying packages retail to browsing the Internet and finding lots of stuff. So it was changing people’s behavior radically.”

The educational software industry was poised for downsizing. But did O’Leary hasten its demise?

In 1999, Mattel bought TLC for (US) $3.6-billion. O’Leary was made president of Mattel’s TLC division. Six months later he was fired when it was discovered that TLC was a money-losing pit, blowing a hole in Mattel’s stock and its bottom line. Mattel’s stock lost (US) $2-billion in value in one day when TLC’s woes were finally revealed. The CEO of Mattel, Jill Barad, was axed and TLC was sold off for (US) $27-million in late 2000.

In his 2011 book, O’Leary claims that Mattel’s plodding bureaucracy prevented him from putting his plans into action to make Mattel’s characters like Barbie interactive. Barad, he claimed, wouldn’t take his calls either. “The top of my head would blow off,” he writes. “Then I’d hang up. And so it went.” He said Mattel had a slothful and arrogant culture that could not accommodate the hard-charging, entrepreneurial and workaholic disposition of TLC.

But had O’Leary sold Mattel an empty suit? Analysts like McGowan had counseled Barad not to buy TLC, calling it a “house of cards.” Howard Schilit of CFRA, which had examined O’Leary’s operation, says he was not surprised by TLC’s collapse. “I had concluded that Softkey/TLC had a very weak foundation built on a series of roll-ups and would be a huge risk for any buyer of the company,” he says.

And when forensic accountant Alan Mak, a partner of Ferguson + Mak LLP, examined TLC’s financial statements for the Observer, he explained that a lot of the high tech companies of the 1990s abused accounting rules. “TLC and other companies are precisely why the rules were changed," he says. Indeed, the SEC issued a letter in 1998 warning software companies about their tendency to overestimate the value of software and unfinished technology.

Video game industry veteran Bernard Stolar was hired in January of 2000 to try and revive TLC. But after he brought in a forensic accountant, he discovered the division was losing $1-million a day. “Jill (Barad) got a sick company,” he says. “She didn’t get great guidance.”

And then there are allegations made in a series of shareholders’ lawsuits launched against Mattel in the wake of the TLC debacle. In one drafted by the San Diego, CA-based law firm Milberg Weiss Bershad Hynes & Lerach LLP in 2002, they paint a dark picture of O’Leary’s involvement in the catastrophe.

The lawsuit claims that at TLC, O’Leary and the company’s CEO, Michael Perik, prior to the sale to Mattel, allegedly inflated the company’s numbers via a number of methods. It says they knew that the company had large uncollectible accounts receivable, that they had secret return obligations with major customers (whereby they didn’t have to return unsold products), and that they delayed reporting returned merchandise to make quarterly numbers look better. It also says they parked product with distributors and liquidators, sent excessive product to customers far beyond their needs in order to record them as sales, and even rented excessive floor space with retailers to give the appearance of increased market share.

These allegations were never tested in court, however: this and other lawsuits were rolled into a (US) $122-million settlement paid by Mattel in 2003 – the 12th largest shareholders’ settlement in US corporate history at the time. Mattel’s lawyers, meanwhile, say the settlement admits no wrongdoing and did not cost the company anything because it was covered by its insurers.

O’Leary, in his book, devotes a couple of pages to his firing and the lawsuits, omitting the serious allegations leveled against him, and the enormous sums of money lost by shareholders with TLC’s demise.

Scott Murray, who was CFO of SoftKey/TLC from 1994 until 1999, remains an O’Leary loyalist, calling him “the Mark Zuckerberg of the ‘80s and early 90s" by introducing the idea of selling low-price software.

And like O’Leary, Murray says TLC was a perfectly sound company when it was sold to Mattel – in a deal he says enriched TLC’s shareholders. “It was doing great, yup. It was doing great,” he says.

Murray also denies the charges that they were artificially boosting TLC’s sales, or that TLC wounded the educational software industry fatally by under pricing its wares. And like O’Leary, he blames Mattel's management for TLC's demise. “They bungled it,” he remarks. “Software companies are not like apartment buildings… If you don't develop new product and only milk what you have and don’t integrate properly, they can decline very quickly. Unfortunately, that's a life cycle of the software company.”

The Observer made efforts to reach O'Leary through his book publisher and former investment firm, O'Leary Funds, to ask him about these allegations, but did not hear from him.

Educational software market implodes

What was the impact of the collapse of TLC on the educational software industry? After all, it was the biggest company in the market at that time.

For one thing, most of the design talent went elsewhere. “Yeah, a lot of people migrated over to the gaming industry, the console gaming world and the online gaming stuff,” says Michelle Bushneff, the former creative director at Brøderbund. “A lot of the creative talent from my team migrated over to the film industry.”

Stolar says the collapse of TLC, “killed what was, or what could have been, a wonderful marketplace. You have Scholastic, Pearson – a number of companies that are in the educational area, they don’t touch this area. They are afraid to and this is 15 years later.”

O’Leary may not have single-handedly destroyed the educational software sector of the '90s. The Internet was destined to knock a big hole in it. But those who lived through that era feel he put a nail in its coffin that didn’t have to be hammered. “It was a quick hit and wham bam, thank you ma’am and he was gone as a well off guy,” says Art Willer.

Indeed, observes Stolar, building a company that lasts for a long time, “that’s not what he’s good at. It means you have to work with people, you have to be more careful about what you do and that’s not him.”

Comments