Thunder in the air

Kitasoo Band Council Chief Councillor Doug Neasloss speaks about the rise of ecotourism in his home community of Klemtu and how Coast Opportunity funding has helped protect local wildlife from trophy hunting at the Telus World of Science in Vancouver, B.C. Photo by Elizabeth McSheffrey.

The air itself seemed to thunder as drummers marched stakeholders, the B.C. Premier and Indigenous leaders into the Great Bear Rainforest ceremony earlier this month.

First Nations drumming has become common at official events as a welcome symbol of their power in the province. But this was no mere symbolism — in the Great Bear Rainforest, First Nations are a force to be reckoned with.

The two-decade story of the Great Bear Rainforest agreement is a fascinating window into the ongoing efforts of Indigenous people to reclaim power over their traditional lands.

At one point or another, federal and provincial governments, industry and environmentalists have all been humbled by the Indigenous leaders who built capacity for their communities and asserted authority over their territories.

For First Nations, protecting the Great Bear Rainforest was about more than just land, it was about rebuilding a livelihood for people who have lived in what many describe as “Third World” conditions for generations. Filthy drinking water, dilapidated homes, illness and poverty are rampant in many reserves across the country, and they wanted better lives for their people.

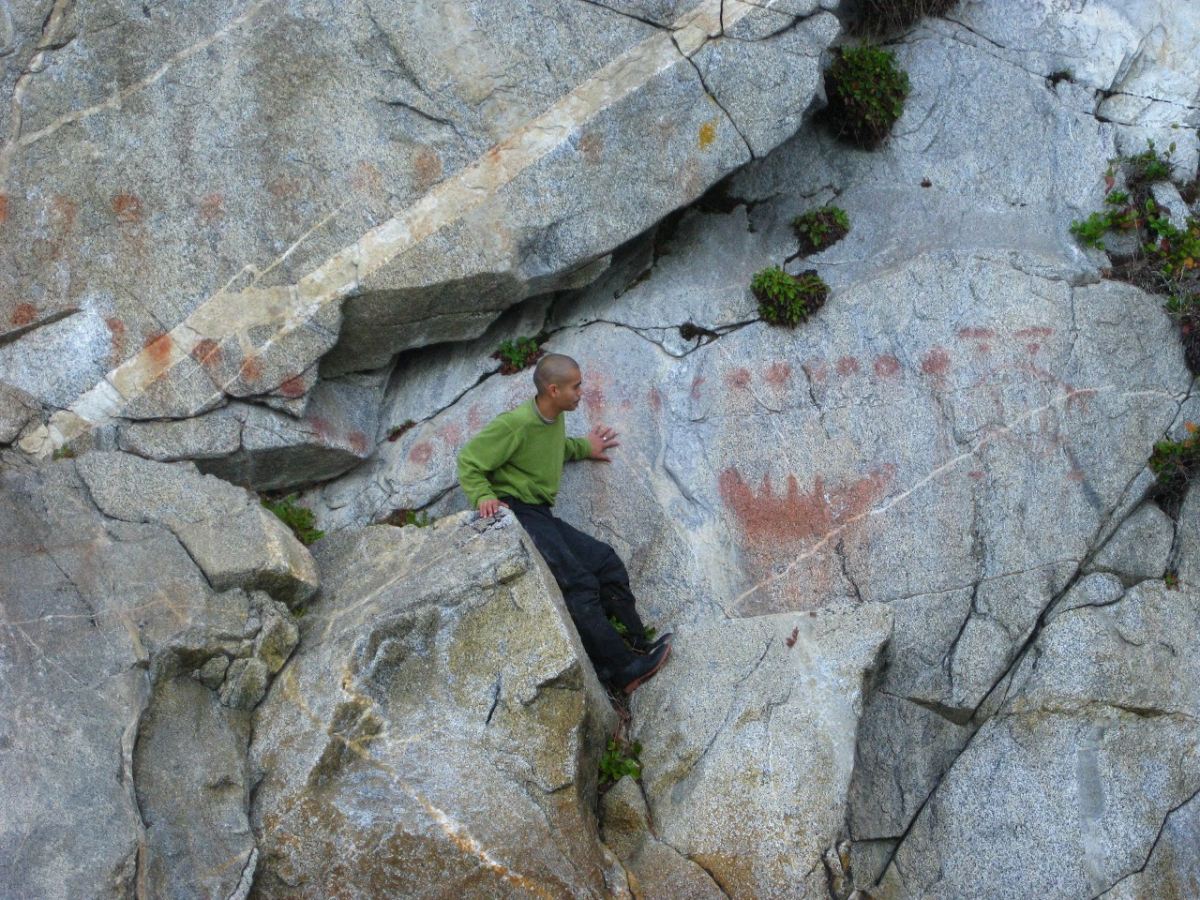

Indigenous leaders were open to new partnerships, new economic opportunities and new methods of managing their land with only one condition: they would steward the territory moving forward, just as they had for thousands of years before environmentalists ever painted ‘Great Bear Rainforest’ on a banner.

Irresistable

An eagle carving overlooks the waters in Campbell River, home of the Nanwakolas Council. Photo by Elizabeth McSheffrey.

The Great Bear Rainforest — incorporating traditional areas known as Txalgiu, Tsee-Motsa, Waglisla, Klemdulxk, Aweenak’ola and more to local First Nations — is a rare and remarkable ecosystem stretching 64,000 square kilometres from the northern tip of Vancouver Island to Alaska. It is the largest coastal temperate rainforest left on Earth, home to robust populations of vulnerable wildlife including grizzly bears, sea wolves, orcas, and northern goshawks.

When First Nations led stakeholders and the B.C. government in hailing a conservation deal for 85 per cent of it, it was momentous occasion in ways that only First Nations could fully appreciate:

“By the time we got to the end of this, we were actually writing legislation that was being passed by the Government of British Columbia,” said Art Sterritt, executive director of Coastal First Nations from 2004 to 2015. “That’s the kind of monumental change we were able to make.”

It was a far cry from the early days of the War in the Woods, when sparring environmental groups and timber companies had anointed themselves the primary protagonists in the battle for the region’s future.

The B.C. government had already characterized First Nations as “stakeholders” rather than decision-makers in early land-use planning for the region, a pattern governments have yet to jettison despite a string of court victories following the landmark 1997 Delgamuukw court case confirming Indigenous rights and title.

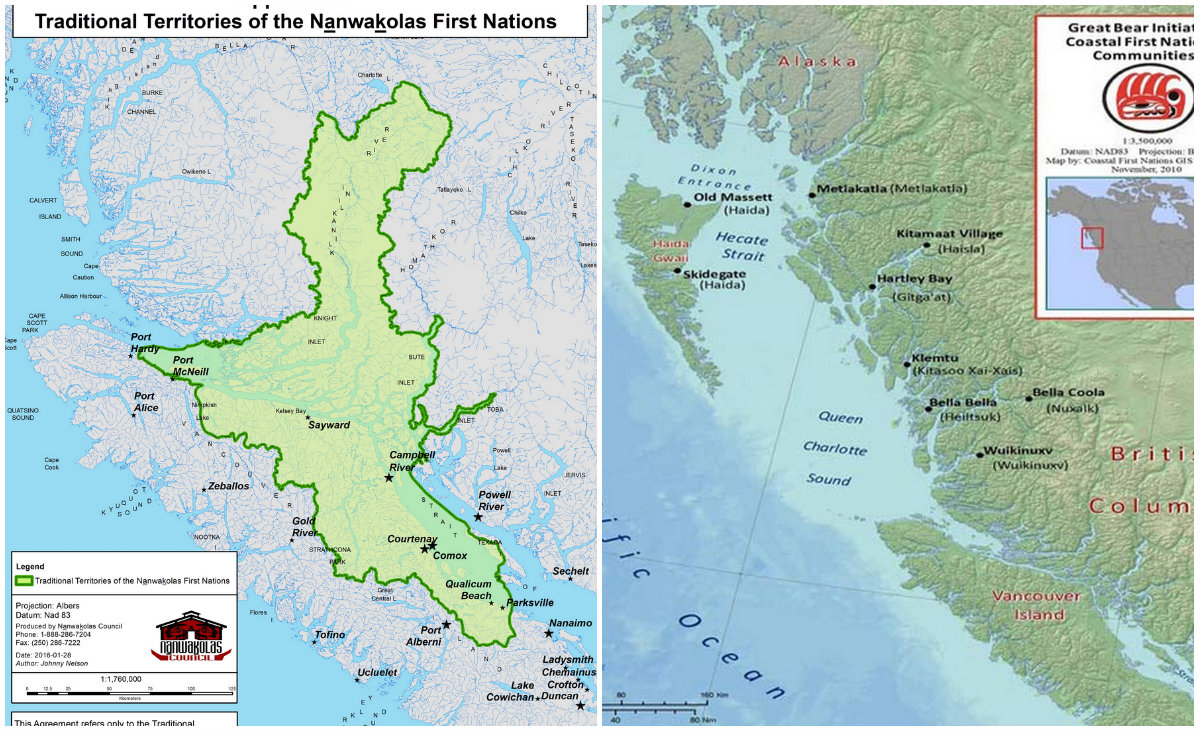

“We had to live with hundreds of land use designations and zoning decisions that got applied to our territory without our consideration,” explained Dallas Smith, president of the Nanwakolas Council, representing six of the 26 First Nations that have traditional territory in the Great Bear Rainforest.

“So when they finally came to us and asked us if we were prepared to participate in the planning, we couldn’t allow another process to happen under our noses.”

For many years, First Nations had mostly operated community by community, often in isolation from one another. Facing the enormous political and financial power of industry in the late 1990s however, they realized they were stronger together.

The nations formed two governing bodies to represent them in negotiation: Coastal First Nations for those in Haida Gwaii and the Northern and Central Coast, and the Nanwakolas Council for nations on northern Vancouver Island and the South-Central Coast.

They became an irresistible force, using their combined power directly in negotiation with government and industry, and indirectly by leveraging effective environmental campaigns. It forced the timber companies to the table to talk.

“First Nations came together at a time in their history when they knew if they did not save the region at this point in time, that all that was precious to them would be gone,” said Sterritt. “That really is the story from the First Nations side.”

Power

Nuxalk Nation members join Greenpeace activists in blocking a logging road on King Island on their traditional territory on June 1, 1997. The RCMP arrested 24 activists and by October 1998, Interfor successfully cut down the majority of trees in Ista, the sacred land of the Nuxalk Nation. Photo by Greenpeace, Greg King.

The stakes on the table were very high. The scars of colonization ran deep, and the abundant natural resources of the ocean and rainforest that had once sustained thriving cultures had been appropriated by heavy-handed logging and commercial fishing along the B.C. coast.

The fate of their culture, language, and livelihood rested inextricably with the fate of the rainforest, and the goals of Indigenous leaders were straightforward: preserve the ecosystem by restoring sustainable resource management practices, and do it in a way that improved the quality of life for communities along the coast.

It was easier said than done, said Sterritt.

One early initiative was ensuring that the B.C. government, conservationists, and logging companies were working from the same set of scientific understandings. Beginning in 1999, each group had approached First Nations with its own information about the rainforest ecosystem, that they, as residents of the region, deemed outdated and factually incorrect.

The leaders challenged everyone to put resources on the table for First Nations to commission research that would eventually define ecosystem-based management practices and land-use planning in the Great Bear Rainforest.

Several of the communities, including the Kitasoo/Xai’xais and Gitga’at had already been developing their own land-use plans for their territories, and in the early 2000s, shared them with stakeholders and the provincial government.

Dallas Smith served as a member on the new Coast Information Team and Sterritt co-chaired.

“We were holding the pen to make sure that was all getting done,” Sterritt explained. “That’s a very important thing because that got away from all that arguing that was going on at the table.”

By 2001, First Nations had led the process to a new five-part framework for conflict resolution based on the principles of ecosystem-based management, independent science, strategic logging deferrals during negotiation, and economic diversification in the region.

Perhaps the most significant part, however, was the signing of a true government-to-government General Protocol Agreement between eight coastal First Nations and the province.

“It was quite the evolution,” said Smith. “Instead of being used as pawns in the overall discussion about the War in the Woods, we became the important players and started to build partnerships.”

But the work was far from over — more than a decade of emotionally-exhausting and occasionally infuriating negotiation followed. At times, Smith felt that for every step First Nations took forward, something pushed them three steps backwards.

Insanity

A beautifully-carved totem pole in the Klemtu Big House. Photo by Jens Wieting of Sierra Club BC.

One of the challenges least understood in non-native circles is the crippling issue of capacity for First Nations bands facing a barrage of industry and development proposals. Many of them lack the financial resources, experience, staff and technical expertise that allow meaningful evaluation and consultation with politicians, conservationists and loggers.

In the early 2000s, Indigenous leaders needed scientific evidence for the conservation of their territories, complex cases for philanthropic funding, and proposals for the economic diversification of their communities. It was a task that many, like Tlowitsis Chief John Smith, found incredibly daunting.

“Forest companies at the table… would bring in a stack of maps and say, ‘Is this okay?’” he recalled. “I would say, ‘Why didn’t they bring us in when they were putting it together? Right now I don’t like it because I don’t know what the hell you’re doing except showing me a bunch of pictures.’”

First Nations needed cash to hire finance experts, forestry technicians, and conservation biologists to build up their stewardship offices and interpret the packages being placed before them.

Chief John — who is also Dallas Smith’s father — faced additional challenges caused by the colonization of his traditional Tlowitsis homeland on Turner Island. Having been forcibly moved onto designated reserves, his people were later forced to abandon their homes in the 1960s after the closure of government schools and medical centres.

Today, the Tlowitsis are spread out across reserves and major cities, which made collecting their opinions and representing them at the Great Bear Rainforest negotiating table an incredibly difficult task:“Our people are scattered all over the place, so you can’t get one big voice one way or another,” he explained from Campbell River, where the nation maintains a permanent band office.

It took extensive outreach through regional treaty meetings to finally gather all the voices of his nation members.

“It will drive you crazy,” Chief John chuckled. “It’s a real process to be involved in, but it controls the big companies to a degree that is helpful in protecting some resources for the future of our people.”

He is now proud to show visitors a set of buttons made by environmentalists saluting his “survival” through each of the major Great Bear Rainforest breakthroughs in 2001, 2006, and 2009.

They’re a tongue-and-cheek reference to the taxing nature of the deliberations, but at times, even his son, Dallas Smith, a man known for his sense of humour, struggled to find the silver lining. He admitted to spending tearful nights at his home during the many years of negotiations, and on several occasions, wanting to quit.

The pace of progress often seemed stagnant, he explained, and it was enough to make him lose his mind.

“This made me understand what depression truly is,” he said, sitting across the table from his father. “It seemed unending. It’s sort of the definition of insanity — I’ve been doing the same thing for 15 years and it’s only in the last few years that we’ve gotten over the hump.”

The crest of that hump came in 2007 when nebulous promises about “sustainable economies” were replaced by real financial investment. First Nations and the philanthropic community finally joined the politicians in announcing a Coast Opportunity Fund that would implement their original vision to combine rainforest conservation with human well-being.

Success

An ecotourism vessel floats casually through the Great Bear Rainforest. Photo by Esther Chetner.

The Coast Opportunity Fund was worth a whopping $120 million, pieced together by the provincial and federal government, and a handful of philanthropic organizations.

The cash was divided into two $60-million pots, an Economic Development Fund for creating diverse and sustainable business opportunities, and a Conservation Endowment Fund for helping First Nations effectively manage protected areas and protect their cultural resources.

But it didn’t land miraculously in their laps — it took years of relationship-building between First Nations, private funders and governments, and encouraging stakeholders to put their money where their mouths were.

“[The fund] has definitely been transformational,” said Chris Roberts, regional economic development coordinator for the Nanwakolas Council. “If it weren’t for this, I wouldn’t be back home working not just for my nation, but multiple nations in the region I live.”

Roberts, a Campbell River native and member of the We Wai Kum Nation, graduated from the University of Victoria in 2008 and completed a B.C. government’s Aboriginal Youth Internship Program. He had always wanted to return to his traditional territory, but knew there were no employment opportunities there for an economics major.

But when the Coast Opportunity Fund was announced in 2007, the Nanwakolas Council needed someone to manage the economic development process. Roberts was hired in 2009, and now helps local businesses apply for grants from the fund, and diversify their partnerships and opportunities in the region.

In the Nanwakolas membership alone, he has seen more than $500,000 from the Economic Development Fund turn a Tlowitsis shellfish farm into a profitable venture, launch successful tourism initiatives for the Mamalilikulla Qwe’Qwa’Sot’Em, and run youth-to-elder culture and language camps for the We Wai Kum, We Wai Kai, and Kwaikah.

Most importantly, he said, he can now tell his seven-year-old nephew who says he wants to be a conservation officer that there is an employment future for him in the Great Bear Rainforest.

“I just smile and grin and say he won’t be a conservation officer, he’ll be a guardian of his territory,” Roberts said. “By the time he’s of age, hopefully we’ll have achieved the establishment of these programs to the point where they’ve got good capacity, recognition and perhaps even authority over the management and stewardship of our lands.”

Further north in the Great Bear Rainforest, a robust Coastal Guardian Watchmen program has already been developed for members of Coastal First Nations. It became an independent operation in 2009 thanks to $216,000 in funding from the Conservation Endowment Fund, and now monitors and protects the territories, cracking down on hunters hoping to kill grizzlies and other wildlife.

This helps ecotourism businesses in the area flourish, such as the Spirit Bear Lodge in Klemtu, a small community on Swindle Island in the heart of the Great Bear Rainforest. The wildlife-viewing venture is run by the Kitasoo/Xai’xais Nation and is now the second-largest employer in Klemtu.

With more than $1 million in grants from the Economic Development Fund between 2010 and 2015, the Kitasoo Development Corporation has doubled its occupancy, renovated, advertised internationally, and trained youth in bear-guiding.

“We knew we had to take it seriously and grow this unique opportunity,” said Doug Neasloss, Chief Councillor for Kitasoo Band Council and one of the founders of Spirit Bear Lodge. “We used to run our business out of a small float house and cram six people in this tiny space.”

Governance

Three-year-old Owen Duncan of the Da’naxda’xw and Campbell River First Nations celebrates the conservation announcement for the Great Bear Rainforest with his mother on Mon. Feb. 1, 2016. Photo by Andrew S. Wright.

But there is no silver bullet for overcoming the challenges facing First Nations communities.

As Roberts said, the Coast Opportunity Fund has been “transformational” for many individuals, but Smith said it could be years before substantial human well-being outcomes are reached across the board, like improved employment rates and education enrollment.

“There’s no textbook that says, ‘apply money and it works,’” he explained. “There are various policy barriers in place. You have to set up limited partnerships. You need directors to run those partnerships.

“With a First Nations community that has no capacity, you can’t just give them a $3-million business to run because they don’t know how.”

But there is light at the end of the tunnel, said Smith, who has been wrangling through the Great Bear Rainforest negotiations long enough to know that the progress made in First Nations governance will last forever.

“Before people just told us what to do, then they started telling us what they thought we wanted to hear. Now they’re asking us what to do.”

It’s shame that for the campaign to work, First Nations had to overcome racism and exclusion.

He still remembers the first stakeholder meeting he attended when an industry participant pointed to his chiefs coming through the doorway, and said he couldn’t believe someone “let those goddamn Indians into this process.”

But times have changed.

“It took us a while to realize the role we had as leaders and to do it properly,” he explained. “The concept of the Great Bear Rainforest has helped us gain momentum for what we’re trying to do in our part of the Great Bear Rainforest. We made it about more than just about the Kermode bear and the protected areas.”

Since then, both the Nanwakolas Council and Coastal First Nations have been approached by Indigenous people in Nunavut, First Nations in the Boreal Forest, and aboriginal groups in Hawaii, the South Pacific, and South America. All sought advice on how to build relationships with governments and stakeholders in the fight to protect their title, lands, and cultural resources.

This steady rise to power has been humbling to watch, said Ross McMillan of Tides Canada, who worked alongside Indigenous communities in the Great Bear Rainforest to help raise conservation capital.

“I was really struck by their generosity of spirit and also the absolute depth of resolve in terms of their visions for their territories. In spite of years of government neglect and heavy-handed companies in the region, the First Nations were remarkably open to new ways and new forms of partnership with the environmental community and beyond.”

Jody Holmes, director of the Rainforest Solutions Project and a lead environmental negotiator, further credited Indigenous leaders with being the first at the table to take “the long view,” and envision rainforest protection as encompassing the people who live there.

“That’s a huge part of this story,” she said. “From a basic social justice perspective, that’s a complete game changer, a complete shift.”

At an event in Vancouver earlier this year, Smith saw a satellite photo of North America snapped from space at night. The twinkling yellow lights of development dominated the majority of the Americas, but the Amazon, the Canadian Arctic, and the Great Bear Rainforest were completely dark.

It was a striking and validating image, he said.

This article is part of a series produced in partnership by National Observer, Tides Canada, Teck, and Vancity to highlight the stories, people, and history behind the Great Bear Rainforest conservation agreements. Tides Canada is supporting this partnership to foster integrated solutions for conservation and human well-being. National Observer has full editorial control and responsibility to ensure stories meet its editorial standards.