Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Two national Indigenous organizations are demanding an explanation from Prime Minister Justin Trudeau after they were excluded from a discussion on the role of Indigenous people in tackling climate change in Vancouver last week.

Both the Congress of Aboriginal Peoples (CAP) and the Native Women’s Association of Canada (NWAC) were not invited to a meeting on March 2 between aboriginal leaders, premiers, and the Liberal leader.

“What this action of excluding us translates into is third-class treatment,” said National Chief Dwight Dorey of CAP. “We’ve just passed the 100-day milestone with our new government, and already Indigenous peoples are being left out of federal negotiations.”

Dorey was invited by the federal government to attend COP21 negotiations on climate change in Paris, but didn't get an invitation to the exclusive meeting in Vancouver. Both CAP and NWAC have been considered among the five major organizations representing Indigenous people in Canada since the days of the Kelowna Accord, along with the Assembly of First Nations (AFN), the Métis National Council (MNC), and the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK).

The latter three groups were included in the meeting, but the paper trail offers very little explanation as to why the first two were not.

On Feb. 10, CAP sent a letter to Trudeau’s office expressing “extreme disappointment” with its exclusion from the climate change meeting scheduled on March 2. The organization represents more than 1 million Indigenous people living off-reserve, including status and non-status aboriginal people.

“… You committed to including all of the five National Indigenous organizations in high-level discussions when the issue impacted Indigenous people,” the letter stated, referencing a December 2015 meeting between the prime minister and Indigenous leaders. “Undoubtedly, climate change is one of those issues that will affect our Peoples for generations to come.”

The organization asked for an immediate invitation to the discussion, and nine days later, the prime minister responded. His letter, however warm, did not extend an invitation or provide an explanation as to why CAP was excluded:

Although NWAC did not issue its own request for invitation, it has still not heard from the federal government about its exclusion from the meeting, despite media coverage detailing its disappointment. When questioned by National Observer as to why NWAC and CAP were intentionally left out, the Prime Minister’s Office forwarded the question to the Office of Indigenous and Northern Affairs, which issued the following statement:

“The Government of Canada is committed to a renewed, Nation-to-Nation relationship with Indigenous Peoples, based on recognition of rights, respect, co-operation and partnership. This meeting does not in any way preclude ongoing discussions, as committed to by the Prime Minister in December 2015, with all five National Aboriginal Organizations. Over the coming months there will be additional opportunities for further dialogue for all Canadians, including Indigenous and non-Indigenous organizations to share their comments and engage in this issue that affects all Canadians.”

On March 1 — one day before the meeting would be held in Vancouver — the Aboriginal Affairs Working Group, whose membership includes the provincial and territorial governments along with the five major National Aboriginal Organizations (NAO), reached out to CAP and NWAC.

Their letter of support indicated that the premiers had not been consulted on the decision to exclude them, and reiterated their importance of having their voices at the table in advancing Indigenous issues:

“We didn’t have a chance to defend ourselves.”

When the meeting between premiers, the prime minister, AFN, ITK and MNC finally occurred last Wednesday, Dorey was barred from entering. The president of NWAC however, Dawn Lavell-Harvard, did manage to attend by personal invitation from the Ontario government.

Still, she said she was not able to speak, “relegated to the back row” as a 'guest' rather than a participant.

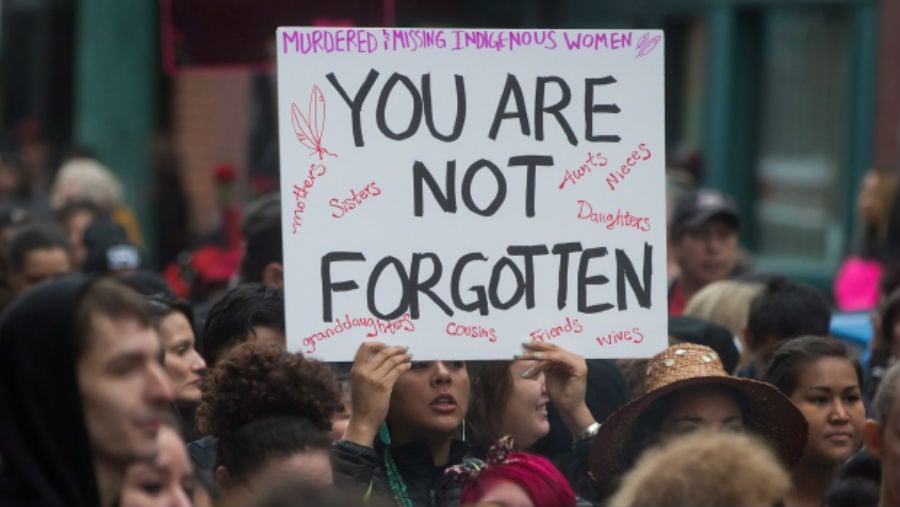

“They’ve all been talking about ending violence against women and girls, but to be unilaterally excluded from this meeting — to have our voices sidelined on an issue that is in fact very important and very much impacts aboriginal women is symbolic violence,” she told National Observer.

“We didn’t have a chance to defend ourselves or make a case for why we should be there.”

Other provinces brought Indigenous leaders to meeting as well, including British Columbia. Dallas Smith, president of the Nanwakolas Council, came as part of B.C.’s delegation and said no one outside of AFN, ITK and MNC was permitted to speak, despite the best efforts of Premier Christy Clark.

“We understood how it played out, but we were pleased that she at least stood up and tried to give us her opportunity.”

According to the office of Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne, which brought Lavell-Harvard from NWAC, the decision on who would speak and which organizations would participate in the meeting belonged to the federal government as the host of the event.

Her senior press secretary Jean-Simon Farrah said the office felt it “was important for [Lavell-Harvard] to be there," but couldn’t comment further on the matter. Outside the meeting however, Wynne made the following statement to reporters:

“If we don’t find a way for the federal government, the provincial government and Indigenous leadership to work together better on something as fundamental as provision of clean water, then I think that we should be very ashamed of ourselves. So that’s one of the issues that I’ll certainly be pushing.”

A potential issue of rights and title

Though the Prime Minister's Office has not given a firm answer as to why NWAC and CAP were excluded from the climate change discussion, AFN National Chief Perry Bellegarde, who attended the meeting personally, offered his speculation to National Observer:

“My take on that is that the prime minister, when it comes to rights and title, in Canada’s constitution it refers to Indian, Metis and Inuit, and that’s who we had at the table,” he explained. “It doesn’t preclude him on meeting with CAP or NWAC on any issue in the future, but when it comes to rights and title, the rights and title holders have to be represented at the table and that’s who was there.”

His organization has specific youth, elder, and women’s councils that form part of the executive council team, and Bellegarde said AFN strives to represent them to the fullest at all times.

But AFN doesn’t —and can’t —represent everyone, Dorey insisted, given the special focus of both CAP, which includes non-status Indians and Indigenous people living off-reserve, and NWAC, which represents thirteen native women's organizations from across Canada.

“There are still thousands and thousands of people who are not connected in any way to a First Nation that is represented by the AFN,” he explained. “Those are people represented by the congress, and those people need to heard — and I’m not talking about scattered individuals, I’m talking about whole communities of people.”

He further rejected the notion his exclusion boiled down to “rights and title,” as rights to hunting, fishing, culture, and traditional ways of sustaining are accessible to all Indigenous people. Section 35 of the Constitution Act, which recognizes and affirms the rights of aboriginal Canadians including “the Indian, Inuit and Métis peoples of Canada," does not discriminate, he explained, having been present himself at the time the words were negotiated in 1982.

“It doesn’t matter if you’re living in a First Nations community in the northern part of the country or in downtown Vancouver, you have those rights,” he said. “I’ve seen the ups and downs of governments dealing with us in an effective way and then excluding us in another, and it’s something that’s been going on far too long."

Even if it were a matter of “rights and title,” both Dorey and Lavell-Harvard wondered what harm it could have done to invite them. Lavell-Harvard was particularly upset that only male Indigenous leaders participated in the meeting, when Trudeau himself made a gender-neutral cabinet in the fall. It's even more baffling, she added, when you consider the fact that Indigenous women are arguably the most marginalized and vulnerable population in Canada.

A specific stake in the climate change discussion

According to a recent report by Health Canada, some Canadians are more exposed than others to the health risks posed by climate change. Cancer, respiratory disease, heart attack — people who are chronically ill, homeless or have low income are most at risk are most vulnerable to these dangers, along with those who live off of the land, northern residents, children and seniors.

Indigenous women and girls fall into many of these categories, said Lavell-Harvard, and some even fall into all of them. Roughly 17 per cent of Indigenous women live in poverty, and have the fewest resources to deal with these challenges of both aboriginal men and non-aboriginal women. Many already face food insecurity living on reserves, she continued, and struggle to access the public services that could help them.

“You can see how being in every single one of these categories Indigenous women and girls are facing increased risk because there’s a compounding of all of these circumstances,” she explained. “So to not even be allowed at the table was shocking really.”

Indigenous women are also the traditional carriers of water and bearers of children in aboriginal culture, which means changes to the environment — air and water-borne toxins specifically — will disproportionately affect them both in terms of health and their ability to live according to their customs.

“These are things that allow us to see the impacts of climate change upfront, to be more aware,” Lavell-Harvard insisted. “There’s a lot of traditional knowledge that can be brought forward, a lot of practical knowledge about how climate change is impacting our families and communities that was summarily dismissed.”

Indigenous women can't afford to be excluded from a conversation about aboriginal people and climate change, she argued, and joined Dorey in calling on the prime minister to keep NWAC and CAP at the table from here on in.

Working against a pattern of exclusion

Speaking with reporters outside the meeting on Wednesday, Trudeau defended his decision not to invite Dorey or Lavell-Harvard to participate in the discussion:

"I have had over the past months many meetings both with the national aboriginal organizations together but also individually with leaders and communities and the activists from the Indigenous community to talk about the issues facing them," he told reporters.

Both the CAP and NWAC representatives hope their exclusion doesn’t form a pattern, but Dorey isn’t optimistic. Earlier this year, both he and Lavell-Harvard were left out of a health accord discussion in Vancouver with the federal, territorial, and provincial health ministers, and other three NAOs.

They have not received an explanation for that exclusion either.

“I had a lot of hopes with this prime minister when he first got elected and the things he was saying and committing to in the campaign,” he said. “I see it all unraveling now.”

In December, Trudeau committed to including all five NAO groups at the table. In the months leading up to that, his government vowed to renew relationships with Indigenous people. Given these promises, Lavell-Harvard called on the other groups in the NAO to speak up when any of its members are excluded.

“It’s the classic united we stand, divided we fall [scenario],” she said. “I’m really disappointed to see that sneaking into politics. It’s supposed to be about people, about making sure our voices are heard.”

Comments

A man running for office puts me in mind of a dog that's lost--he smells everybody he meets, and wags himself all over.

When you want to test the depths of a stream, don't use both feet.