Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Years after a major oil sands spill struck the Michigan town of Marshall in 2010, the company behind the disaster, Enbridge, was still struggling to show it was addressing one of the root causes of its failure.

At least, this is what the company's watchdog, the National Energy Board (NEB), said in a newly-released draft version of a comprehensive federal audit.

The final audit report, released by the NEB last July, concluded that the Calgary-based energy giant wasn't addressing threats to public safety from its pipelines and failing to adequately protect whistleblowers.

Both the company and its watchdog delivered positive messages about the published audit, explaining it showed how much Enbridge was improving.

But two things were happening behind the scenes before the public ever got wind of the report. Enbridge initially responded to the draft report by denying there were major problems. Secondly, the final report is different from the draft version that was privately shared with Enbridge in February 2015. The NEB, which is also based in Calgary, changed the conclusions in response to 28 pages of recommendations from Enbridge.

These recommendations are now coming to light for the first time in response to a request by National Observer through federal access to information legislation. They show that Enbridge disputed the NEB’s conclusions that it was violating a number of pipeline safety rules and urged the regulator to soften its final report.

The NEB rejected some of these requests by confirming that Enbridge — despite the company's objections — was breaking a "significant" number of rules. But the watchdog agreed to withhold some sensitive information about Enbridge’s operations when it released the final audit report, a few months later.

While both the NEB and Enbridge maintained there were no immediate threats to public safety, two engineering experts told National Observer that they disagreed.

These critics said that the public should be alarmed about how the final report was edited, because the changes show that the regulator doesn’t know how to prevent disastrous spills from happening or how to respond when a catastrophe strikes.

“They don't even understand their limitations and the NEB has no idea what the issues are,” said Don Deaver, a former Exxon pipeline engineer from Texas, who now works as a private consultant after a career that lasted decades.

Enbridge asked NEB to remove sensitive information from audit

Overall, the audit was the result of a 15-month investigation by the NEB, including interviews with more than 200 Enbridge employees, inspections at 20 different field locations and a review of more than 65,000 pages of documents, Enbridge told National Observer.

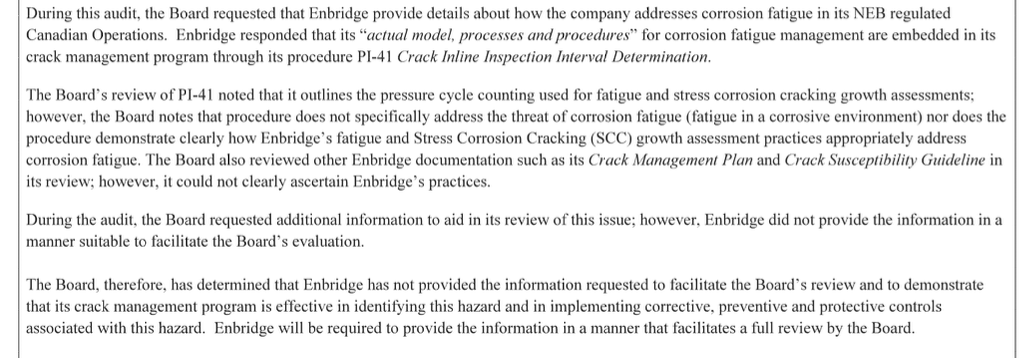

At the end of that process, the draft NEB report included four paragraphs that explained how the company was having trouble proving that it knew how to monitor and repair pipeline cracks forming from corrosion - a key factor that had led to two major Enbridge oil spill disasters in 2007 and 2010 in Glenavon, Saskatchewan and Marshall, Michigan.

These paragraphs said that Enbridge had responded to the NEB’s request for information about “corrosion fatigue” on its pipelines with a document that failed to demonstrate how the company was addressing this threat.

Corrosion fatigue is a chronic industry problem that causes fatal cracks to grow on pipelines, often leading to leaks or ruptures. The problem was flagged in two separate Canadian and American investigation reports into the 2007 spill of nearly one million litres of crude oil in Glenavon, Saskatchewan on Enbridge’s aging Line 3 pipeline - infrastructure that the company now wants to replace and expand - as well as on Enbridge’s Line 6B pipeline, which ruptured and spilled more than 3 million litres of crude into the Kalamazoo River in Marshall, Michigan in 2010.

But Enbridge alleged that the NEB never asked for the information until the end of the audit process when the company said it provided the information.

"As such, based upon the additional information provided and the sensitivity of this matter, we request that all wording in regards to this issue be removed from the final Report," said another section of the 28-page response.

So the NEB wound up deleting those four paragraphs in its final report.

The draft version of another section of the audit, describing how Enbridge protects natural ecosystems, included references to two secret environmental reports. But Enbridge said it didn't want the public to know about those reports and managed to convince the NEB to keep them hidden.

“These reports are confidential, internal Enbridge documents,” the company wrote in its 28-page response to the draft audit report, attached to a letter signed by its president of liquid pipelines, Guy Jarvis, on March 6, 2015. “As such, Enbridge requests that the reference to them be removed from the report, or referred to in a more generic fashion.”

Deletions hide inconvenient truth, says former Exxon engineer

Deaver said these disappearing paragraphs show that the NEB was hiding some inconvenient truth about the pipeline industry: Enbridge is struggling to figure out how to stop leaks on aging pipelines, and officials still don't know the best way to completely clean up after a catastrophic spill, such as what happended in Marshall.

“They (the industry and the watchdog) are using the wrong methods to analyze the growth of these cracking areas that they find along the pipe,” said Deaver.

Deaver added that if the two secret environmental reports refer to the aftermath of spills, they would expose one of the “dirtiest, darkest secrets of the pipeline industry" regarding the challenges of cleaning up after a major leak.

“Whenever there’s a lawsuit on a spill or something like that, the agencies allow the companies to hold back the reports until there’s a settlement,” Deaver said. “It could be embarrassing to the regulatory people (to reveal what’s in these company reports) because it could show that they (regulators) failed to take action.”

The NEB refused a request - through federal access to information legislation - to release copies of the environmental reports that it reviewed in the audit, explaining that it had only reviewed them at Enbridge offices and left them behind, without making any copies.

This is the second time in recent months that the NEB has done something like this: In December, it declined to release an internal corporate investigation report into a damaged pipeline buried by TransCanada Corp - Canada’s second largest pipeline company - because the NEB said its staff left that report behind at the company office in the middle of a separate investigation into serious safety allegations that were raised by a whistleblower.

It's not clear why the NEB would leave documents behind since it has full powers of inquiry and full powers of a federal court to investigate pipeline safety matters. These powers allow the NEB, under Canadian law, to take any evidence it needs to complete its investigations.

But the regulator, governed by a board that currently has 13 members - 12 of whom were appointed by the Conservative government of former prime minister Stephen Harper - wasn’t willing to provide a detailed explanation about any of the unusual decisions made in its recent investigations.

It declined to answer 10 out of 11 questions raised by National Observer about the changes it made to the Enbridge audit report. Instead, it sent a short email with a web link to its audit protocol - which requires it to send draft audit reports to companies for review - and a web link to the final 654-page report that it published on Enbridge.

“NEB audits are conducted to the highest standards of fairness and integrity,” Darin Barter, the NEB spokesman, wrote in the email. “We will not compromise public safety or the protection of Canada’s natural environment during our oversight of Canada’s network of pipelines.”

The NEB also failed to respond to follow up questions asking for clarification. But Barter's comments are part of the main message that the NEB wants the public to hear. This message - that safety is a top priority for the NEB - is a key component of a communications strategy that the regulator adopted in 2014 to boost its public image.

The NEB launched that charm offensive following criticism from environmentalists and other leaders, including from federal Liberals when they were in opposition in the House of Commons at a time when the former Conservative government overhauled Canada's environmental laws, reducing its oversight of industry.

The critics said the regulator was too cozy with industry and needed to be more transparent about its operations. Now in government, the Liberals have pledged to “modernize” the regulator and proceed with longer-term “reforms” to federal environmental oversight in Canada.

Enbridge says its pipelines are safe, but still sees room to improve

Enbridge told National Observer in a statement that the final audit determined that it was successfully protecting the safety of people, the environment and its pipelines. But the company recognizes that it still could do “even better," said spokesman Graham White in the statement.

“We continually strive to make our operations safer because we believe that every incident can be prevented,” White said. “The cleanup of any spill is conducted in compliance with all government regulations and Enbridge’s own stringent and scientific standards for safety and the environment.”

He added that the company consented to the NEB’s release of its 28-page response to the draft audit.

“The only information Enbridge requested to be redacted were the specific references to two environmental reviews bound under law to solicitor-client privilege,” White said. “Any changes made were only to correct factual inaccuracies or to provide clarity. For example, the NEB mistakenly stated that Enbridge had failed to provide the requested information on corrosion fatigue, and Enbridge pointed that out.”

After reviewing what was changed in the audit report, Evan Vokes, a former pipeline engineer who worked for TransCanada, said he was skeptical about the claims made by both the industry and its regulator. He believes pipelines would be safer if the regulators did a better job enforcing the rules.

“I think they’re trying to hide a safety risk,” Vokes said in an interview. “They continue to promise better and better performance on corrosion-related failures and they never manage to stop corrosion-related failures.”

U.S. officials blamed Enbridge for having a “culture of deviance” that contributed to the Michigan spill, which traveled about 50 km downstream on the river that leads to Lake Michigan. But the company and its regulators said that they were taking steps after the 2010 spill to prevent future disasters. Industry and federal officials had made similar statements after the Saskatchewan spill of 2007.

Some critics have also expressed concerns that a another disaster may be looming on Enbridge’s Line 9 pipeline, that is now sending about 300,000 barrels of oil from the West to the East through the Toronto and Montreal regions. But both the company and the NEB have said this line faces stringent operating conditions.

White added that Enbridge, which is still hoping to proceed with plans to build its Northern Gateway pipeline from Alberta to the Northwestern coast of British Columbia, continues to improve its safety performance. It spent nearly $1 billion last year on efforts to “maintain the fitness” of its systems and “detect leaks” in its pipeline infrastructure across North America, he said. Overall, it has made nearly $5 billion of these types of investments in the past four years he added.

Enbridge’s goal, White added, is to provide ongoing and long-term monitoring to ensure it restores the site of any spill to a state that is acceptable to local communities.

Comments