Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

"Freedom."

A young Syrian newcomer to Canada blinks her large brown eyes and cocks her head to the side. "What's this word? Can you explain?"

Fatima Sua'ifan, 13, sits on the carpet of her home in Surrey, British Columbia, translating English and Arabic for her family. Her father, Bassam, holds her baby brother and fields my questions.

For girls like Fatima, freedom in Canada is the option to become something that may have been out of reach before.

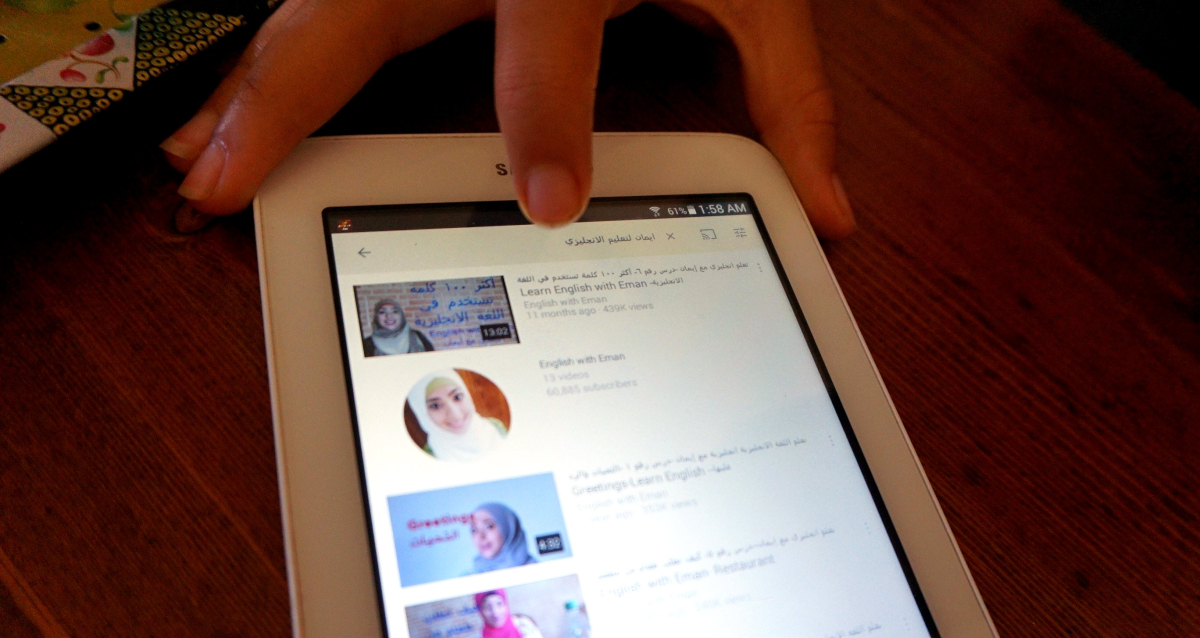

In the span of just eight months, she's become fluent in English by studying with the help of the YouTube series "Learn English With Eman," in which a Muslim woman posts weekly videos teaching students how to greet people, talk about their jobs, and identify family members.

Although it's been five years since she's seen the conflict in Syria, she's glad that her family found safety in Canada. Her brother Yousef, she says, was so fearful of the aerial bombings in their home city of Daraa that he changed his sleeping habits to start dozing off at noon, so that he'd be unconscious while the attacks were happening.

Things are generally going well at school, she says. She's the star of the home economics class — "I cook at home every day," she says.

I've met with the Sua'ifan family a few times since they helped initiate a "Thank You Canada" event on behalf of refugees over the summer. Fatima was selected by the community as a spokesperson to represent Syrian youth, and she made a vivid impression with her optimism and language skills. She'd arrived in February and was already conversing in English. Her English has improved considerably since September. She understands most questions and her vocabulary has grown.

Around 30,000 refugees from Syria have settled in Canada and of those living in Metro Vancouver and Fraser Valley, around 44 per cent — over 3,000 — have settled in Surrey, a major multicultural hub and the fastest-growing city in Metro Vancouver.

Recently, I interviewed her father Bassam, whose story is told here. He and his wife, Yousra Alqablawi, are raising seven children: Mariana, 15, Fatima, 13, Yusra, 11, Yousef, 6, Mohamed, 4, Rahaf, 3, and Karam, 10 months.

When I explain the meaning of freedom — or hurriyah حرية — in Arabic, Fatima nods in complete understanding.

"Freedom" stirs mixed feelings for some refugees.

One Syrian father told me over the summer that he's nervous about the freedom Canadian kids seem to have. He wonders if his own teenage daughters might be influenced by bad behaviour.

Walking through a Surrey neighbourhood with a high Syrian refugee population, I overhear a woman bellowing, "Selling sex is a crime, you turkeys!" to no one in particular.

An hour before my conversation with Fatima, her father Bassam and the volunteer team at the Refugee and Immigrant Welcome Centre, a new facility which Bassam and others worked to establish in August, had organized a seminar for Syrian refugee families about how to successfully raise their children in Canada.

Anxious-looking Syrian parents and a man in his twenties who has no kids but simply wants to learn English assemble. According to the seminar, Canadian youth tend to prioritize their peers after 11 years of age.

Most anyone who has grown up in an immigrant (which is around 40 per cent of Metro Vancouver residents, according to a 2011 census) knows the delicate tug-of-war between adapting to Canada , particularly if the values of one's birthplace collide with Canadian norms.

But spending time with Fatima and her sisters, it's hard to imagine any parent would being concerned. They diligently clean, cook, and take turns looking after their younger siblings. When Mohammad starts playing with a small fruit knife that his mother used to cut up an apple, Fatima gently pulls it away.

"Here in Canada, there's no problem," Fatima said. "We have some rules. We know we can't drink alcohol, or..." she points to the headscarf covering her shoulders and chest, gesturing that they know they have to dress modestly.

"Acceptable" clothing is subjective and many girls from Muslim families choose to leave their hair uncovered, but Fatima covers her hair and neck, and wears long sleeves and pants. While their mother wears the more traditional abaya (a flowing long-sleeved robe), the girls opt for jeans and flowing cardigans. Modesty in moderation.

She asks about Halloween; this strange North American holiday where fake cobwebs spontaneously appear on doors and plastic rats infest bookshelves.

"I'm so scared!" she says, with a mix of amusement and horror as she shows me Google images of party-goers in their mid-twenties, dressed up as corpses, men with dyed hair and Heath Ledger's Joker-style makeup. "Why do people like this?"

Right now, Fatima admits she’s not able to concentrate on the studies she'd prefer. She identifies as a STEM (Science, technology, engineering and mathematics) girl, and boasts that she scored 99 per cent math scores at her last school, in Jordan. She was the top student at her grade level; in Syria, they put the photo of the student with the highest grade in front of the class, and her photo often graced that coveted spot.

If she were a Harry Potter character, she'd be Hermione Granger. Her lowest score, she confesses, was 80 per cent. "It's so bad, for me," she shudders, mortified.

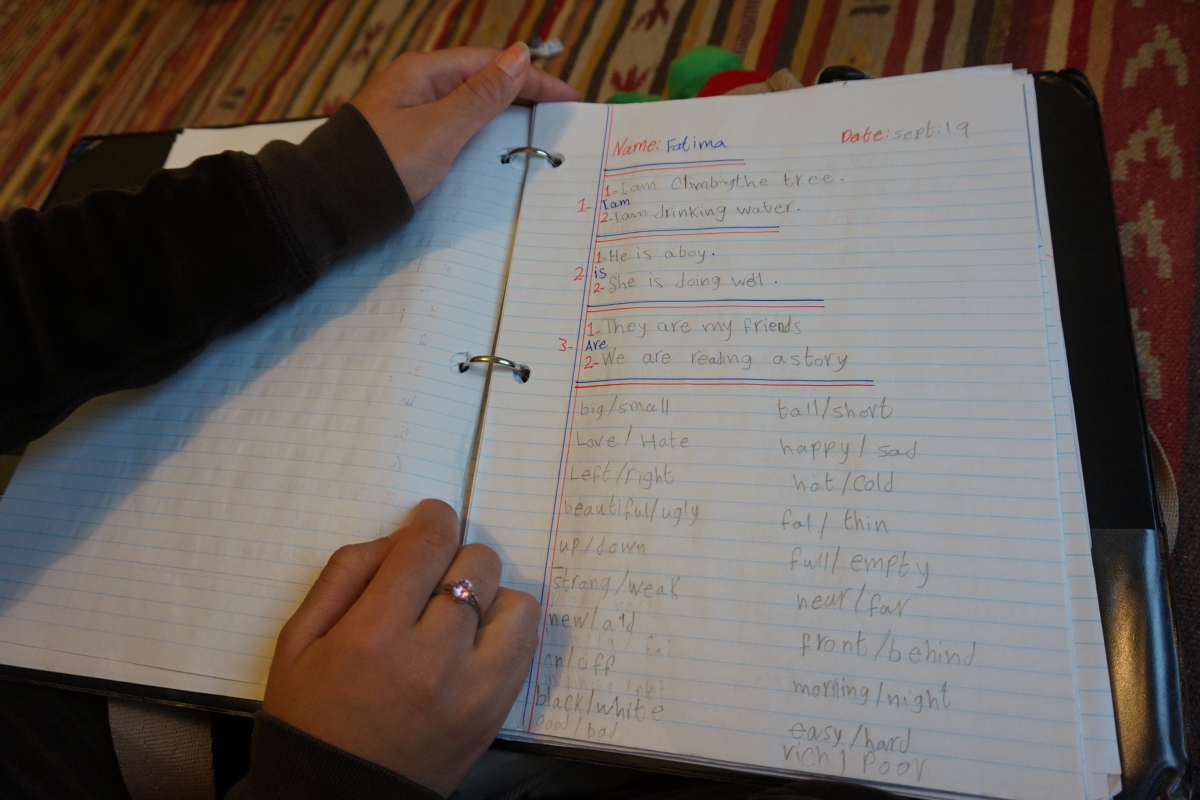

But for now, both math and science have been cut out of her curriculum entirely as she catches up on basic English. Even though she speaks clearly enough, writing is still a challenge.

As she shows me her exercise book in English, many of the worksheets are close to perfect. On a quiz worth 20 points, she's scored 21, answering the bonus question correctly as well.

As a former top student, the idea of taking baby steps and learning beginner-level English, is agonizing. She said she's tried to look up what Canadian eight-graders are studying in science and math online, but found herself facing a a wall of unfamiliar English letters.

"You know, in math and science, in Arabic I know all the words," she says, with a bit of a huff. "I can speak English, but I can't write and read. With computers, you have to know how to write and read."

She estimates it will take around two years for her to catch up to the Canadian students, but in the long run, she may turn out to be very successful. Immigration and refugees minister John McCallum assured that regardless of Syrian refugees' struggles with language today, the young generation tends to outperform their local-born counterparts.

"The good news is that past waves of refugees have succeeded and the children of refugees actually do better than Canadians in terms of education and post-secondary," he told reporters last week. "And so if you take a longer term point of view, I think it’s a great investment for Canada."

Changing the topic, she picks up her Samsung tablet and shows me a low-res photo of a girl photographed from behind. The girl has long brown hair tumbling down to her waist, lustrous and curly. It almost looks like a Pantene shampoo-and-conditioner ad.

“That’s my hair,” she exclaims, a sparkle in her eye, as she points to the photo.

She shows me dozens and dozens of selfies she's taken on her tablet. Fatima experiments with her long hair, wearing it swept to one side, pulled back, and in cool urban fashion wearing a black baseball cap, posing with her a peace sign by her cheeks (Fatima listens to a lot of Arabic rap music). "Makeup and painting nails, for girls, it's just for fun inside the house, when we have nothing to do," she shrugs.

It's never expressed openly, but there's an undercurrent of anxiety in Fatima's expressions, as though she's uncertain whether Canadians will value her intelligence and individuality. Thankfully, she says she's never been bullied and no one ever made fun of her for wearing the hijab. Canadian kids are "nice," she says.

She mentions that her schoolmates often mistake her for her sisters, because they borrow each others's headscarves all the time. One day, she and Mariana deliberately dressed in similar headscarves and outfits, and her classmates reacted predictably.

"My schoolmates, they said, ‘Oh! You’re both so beautiful, like twins!’" Fatima laughs. But she seems a little surprised that her classmates fail to notice how different she is from her sister, since their personalities and appearance are very different.

Fatima elaborates that she prefers the natural, bare-faced look, for example, while her sister Mariana likes to experiment with makeup; she’s drawn to shoes with “big heels” while her sister abhors high heels and prefers flats.

Her older sister Mariana speaks more softly and haltingly than Fatima.

She's picked up a lot more English since the summer, when she relied on an interpreter.

Unlike Fatima, Mariana is not that keen on math and science and is glad to be focused on English.

Her prized possession is a massive, brick-like Arabic-English dictionary with intricate colour illustrations. It was a gift from a kind teacher in Jordan, who encouraged her to pursue her studies.

Mariana likes reading in English, and excelled at writing tests back home — "95 per cent," she says. She wants to become much better with the language so she master the words and become a pediatrician.

Asked what else she wants to do when she grows up, Mariana gets a far-away look in her eyes.

"My dream is to go to Paris one day," she shares. She wants to see the Eiffel tower, and see the city, which has been in her imagination for years while growing up in Syria. Fatima teases Mariana for being more of a romantic, who enjoys movies like Frozen and enjoys "girl stories," while Fatima loves books and magazines that appeal to both boys and girls.

Beside Mariana and Fatima's siblings, Yousef and Mohammad, play with plastic gadgets and show me a pink-framed photo of three girls.

"My sister! Her friend," Mohammad says, pointing at the girls' faces.

The boys spoke who exclusively in Arabic around each other in the summer, have already started conversing in the new language.

But even though she's learning English every day in school and finding her feet in Canadian culture, Fatima still thinks about the land they left behind in Syria.

After listening to some light-hearted songs by Lebanese singer Nancy Ajram and Arab Idol sensation Mohammad Assaf on her tablet, Fatima opens up a new video, featuring a young man — MC Twistar — rapping instensely about the destruction of Syria, his motherland.

She clicks on a related video, featuring young Syrian children belting out the same lyrics, shouting them out to the camera. For the whole duration of the song, Fatima’s eyes are fixated and unwavering from the screen. When Yusra pokes her sister on the arm to ask a question, the normally responsive Fatima doesn’t even seem to notice, and looks overcome with emotion when the song is over.

Later on, she says she has a dream for the future, once she finishes her studies in Syria and completes her studies.

"My dream is to study and become a surgeon, and help people," Fatima says. Her hardships in Syria and Jordan seem to inform her new career path in Canada. After her years-long journey from refugee to high school student, she aims to carve out a new identity for herself in Canada — hopefully as Dr. Fatima Suai'fan.

Editor's Note: This article is part of a series on Syrian refugees in Canada produced in partnership with United Way of Lower Mainland. National Observer has full editorial control and responsibility to ensure stories meet its editorial standards.

Comments