Meet the young scientists working to get rid of animal testing around the world

At first glance, their experiments look like they belong in a horrific, modern-day Mary Shelley novel.

Five scientists created miniature organs, virtual tissue, human lungs on a microchip and other stunning but gruesome breakthroughs.

But make no mistake. These aren't mad scientists mixing chemical compounds to recreate Frankenstein's monster. They are actually aiming to improve what we know about how human body parts react to different toxins, chemicals and drugs, some of which treat the most common and deadly illnesses, such as heart disease or asthma.

And while the research of these scientists — Shrike Zhang, Kambez Benam, Daria Filonov, Kimberly Norman, and Nicole Kleinstreuer — could eventually mean miracles in the search for cures, they have also made major steps toward lab experiments that are free from animal testing. If these scientists can perfect the models they're working on, they can eventually prove that replicated human systems produce more reliable and valuable results, rendering the use of mice, fish, birds and other species obsolete in experiments around the world.

All five were honoured in Vancouver with the Lush Prize for Young Researchers, and for these animal lovers, it's like having your cake and eating it too.

A 3D printer for human body parts

"I’ve always been interested in creating technologies that can be used for improving human welfare, including how to better heal human tissues that are injured or diseased and how to make better models for more efficient of drugs and organs," said Zhang, an instructor and associate bioengineer at Harvard Medical School in Boston, and recipient of one of Lush's five US$15,000-prizes.

"And of course, I'm an animal lover, so I want to develop technology that will eventually be able to reduce or eliminate animal testing."

Zhang and his partners are creating tiny human organs like livers and hearts, exposing them to different chemicals, and cataloging their responses. While his particular field of science is still "emerging," he said he's already used it in a project for the U.S. Department of Defense, studying which environmental toxins could harm soldiers.

With his prize money, he intends to build an advanced multi-material 3D 'bioprinter' that can produce these miniature organs quickly, and perhaps one day, even cheaply.

"I expect that in the years to come, we can probably create a system that fully mimics human functionality, so we can test anything within the system without using any other kind of models," he told National Observer. "One of the ultimate goals is to be able to produce personalized systems, cells or different components from patients... then you can actually use the miniaturized models to do testing for different individuals."

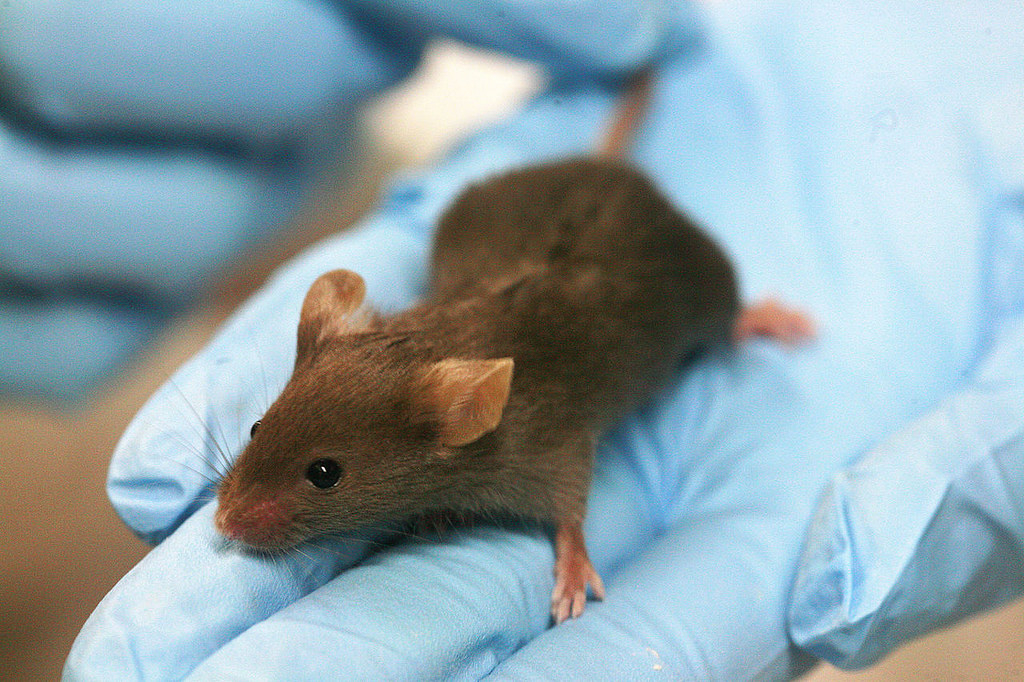

The medical wonder of printing replicates of human organs aside, the research of the young scientists could not have come at a better time for the tiny creatures that usually find themselves under the knife for these kinds of experiments. The use of animals in tests — particularly fish, mice and birds — is increasing across North America.

Animal testing on the rise in North America

According to the Canadian Council on Animal Care (CCAC), animal use in education, medicine, regulatory testing and research at more than 200 certified institutions in Canada spiked 24 per cent from 2013 to 2014, the latest years for which data is available. That's roughly 3.75 million animals, at least 29 of which were subjected to "procedures which cause severe pain near, at, or above the pain tolerance threshold of unanesthetized conscious animals" for the purposes of education alone.

In the U.S., a study conducted by PETA (People for the Treatment of Ethical Animals) and published in the renowned Journal of Medical Ethics also found that use of animals in testing at government-funded facilities grew by nearly 73 per cent over 15 years, from 1997 to 2012. The study estimated that 17 million to 100 million animals are still used in laboratories today, despite scientific advances that are widely considered to produce more effective results.

While Lush, a U.K.-born cosmetics retailer famous for its stance against animal testing and emphasis on organic, ethically-purchased materials, opposes the use of animals for cruelty concerns, they also believe it's practical. As award recipient Kambez Benam explained, animals have different organs and body systems than humans do, which means tests on animals can rarely be relied upon to predict the way a human would respond to the stimulus in question.

In many cases, animal testing "irrelevant"

Benam's research at Harvard uses a tiny human lung airway built onto a microchip to understand how electronic cigarettes affect human lungs and identify the unique genes that distinguish those responses, particularly for patients of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), the third-leading cause of death in the world. Mice don't develop COPD as much as they develop a different strain of emphysema, he said, which means research on the ailment using mice would be "irrelevant."

The same rule would apply for tuberculosis and influenza, he added, just to name a few examples.

"COPD has been around for more than 40 or 50 years, but we have no drug that can stop progression of it," he told National Observer. "If animal models had worked, we would have had a good translation of findings from animals for drug development."

With his prize money, Benam plans to travel to stakeholder meetings, conferences, and lectures in his field worldwide, not only to share his findings but to receive feedback from leading experts.

"They are changing the world," said Hilary Jones, ethical director for Lush. "The older generation are the people handing out the funding for projects, and they're used to doing it a different way.

"This new, non-animal vocabulary is a different science, and these guys that are coming through are starting something different from the start of their career. They really are forging a new frontier."

Globally, Lush will award more than $400,000 in prize money to researchers seeking an alternative to animals used in chemical testing. Scientists are also being honoured in England and South Korea.

Comments

Great news on the one hand but frightening on the other, especially given the fact that much of this increase in animal torture and testing is related to vanity products with absolutely no authentic value, profoundly shameful.

The figures here are a fraction of the world wide "animal studies" business. Stats are not collected in all countries, are greatly underestimated where they are, and animal welfare laws are very lax in most countries.

Raising the animals for testing is yet another way these tragic creatures are mistreated.

Wonderful news that scientists may be able to end this horrific and wasteful treatment of live creatures.