Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Canada’s money-laundering agency is refusing to name the bank hit with an unprecedented penalty for failing to report a suspicious transaction and committing hundreds of other violations in its dealings with clients, including a convicted felon. Details of the failures — including one the agency described as “very serious” — were revealed in documents obtained by National Observer and the Toronto Star.

For nearly two years, the bank failed to report a series of unusual transactions, including some suspicious activity in a controversial client’s account, despite news reports at the time revealing he was under criminal investigation in the U.S. The transactions, involving a number of different clients, included dozens of large cash deposits and hundreds of international transfers worth more than $12 million, reveal the newly-released documents.

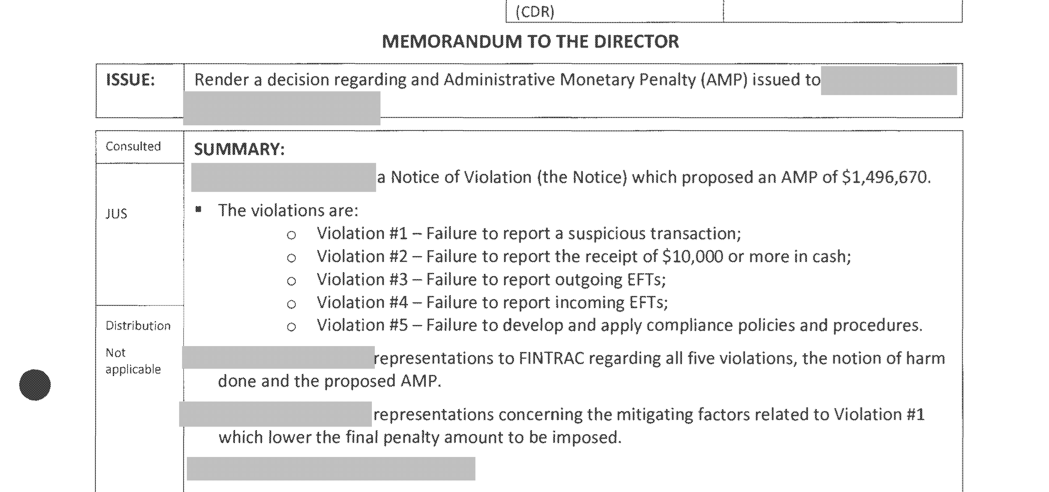

The records, released by the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada (FINTRAC) through access to information legislation, are heavily censored but provide new details about FINTRAC’s first-ever penalty on a bank — $1.15 million, disclosed last April.

Bank identity still a secret

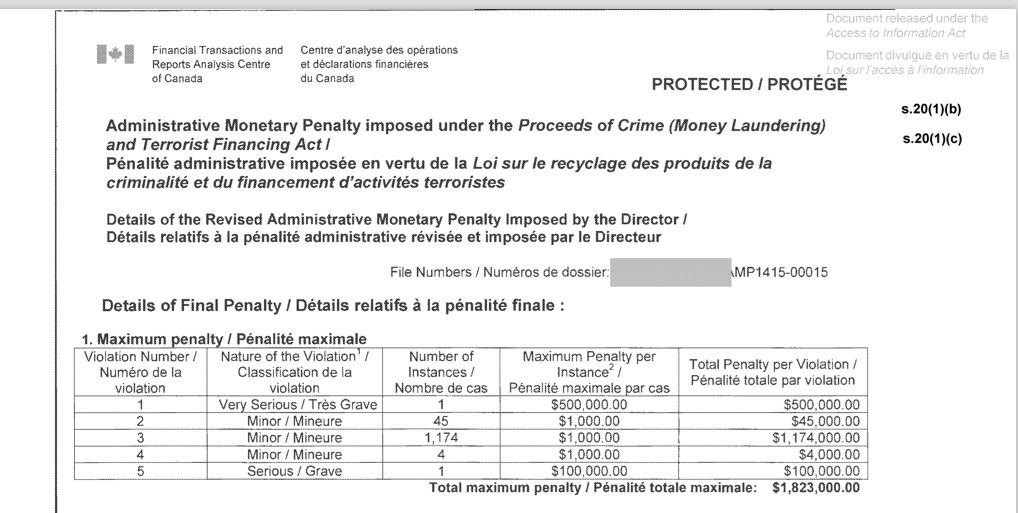

The documents revealed that the bank broke the rules 1,225 times, but the institution’s identity remains undisclosed.

Although FINTRAC also censored the name of the client in the documents, the dates and descriptions of his activities line up with Manitoba online pharmacy entrepreneur Andrew Strempler, who pleaded guilty to mail fraud charges in the U.S. in October 2012 after his shipments were found to contain counterfeit medication.

FINTRAC can disclose to police cases of non-compliance with reporting requirements under money laundering law. But in this case, the bank didn’t face any criminal charges for breaking the rules.

“There… needs to be the criminal intent — we believe — on the part of the entity, so that a charge can be brought forward,” FINTRAC spokesman Darren Gibb said in an interview on Wednesday. “So in this case, we determined that an administrative monetary penalty was the most appropriate course of action.”

Anyone who knowingly fails to report a suspicious transaction to FINTRAC can face a $2 million fine and up to five years in prison, under Canadian legislation on money laundering and terrorism financing. The maximum administrative monetary penalty for the bank's hundreds of violations would have been $1.8 million, the documents said.

FINTRAC reduced penalty from $1.5 million

FINTRAC originally imposed a penalty of $1.5 million, but the agency's director, Gérald Cossette, later approved a decision to reduce the penalty following representations from the bank, including an argument that the harm done was minimal.

The agency said the bank committed the “very serious” offence of failing to report “a suspicious transaction related to the commission or attempted commission of a money laundering offence,” on Feb. 21, 2012 according to the 109 pages of documents.

The facts and circumstances surrounding that incoming February 2012 transaction led FINTRAC to determine there were "reasonable grounds to suspect that the (electronic funds transfer) in question was related to the commission or attempted commission of a money laundering offence," said a FINTRAC analysis document. Therefore, the bank should have reported this suspicious transaction to authorities, the federal documents said. The analysis document also revealed that the transfer was later reversed with the funds returned to the sender.

Gibb said the bank mitigated the harm caused by its actions by reporting two other suspicious transactions, and also by its later co-operation with federal authorities investigating its client in the U.S. and in Canada. Although the FINTRAC penalty against a Canadian bank is unprecedented, it has prompted criticism from skeptics who wondered why the agency declined to name the financial institution.

FINTRAC said it was trying to be discreet.

“The process has concluded and FINTRAC exercised its discretion not to name the entity so that we could send a timely message of deterrence to the 31,000 businesses that are subject to the Proceeds of Crime, Money Laundering and Terrorism Financing Act,” Gibb said.

The documents noted that the bank’s client, who would later be convicted, had been featured in news reports that said he was under investigation in the U.S. related to drug offences. Further, a U.S. Food and Drug Administration investigator confirmed to the bank that an active investigation was underway in 2011.

Because of the timelines involved, at least some of the unreported transactions occurred while Strempler was incarcerated. According to U.S. court transcripts, the U.S. district attorney was able to determine that Strempler made $95 million (U.S.) from his mail order pharmaceuticals business in 2005 and 2006 alone, $20 million (U.S.) of which was put in his wife’s name.

Since FINTRAC only oversees financial institutions, its findings against the bank have no bearing on Strempler.

From early 2012 to the end of 2013, the unnamed bank processed 1,178 international electronic transfers of $10,000 or more. It also accepted 45 cash deposits of $10,000 or more, all without ever reporting the transactions to FINTRAC. The documents also say that the mystery client "used a potential shell company" and operated out of an unnamed country associated with money laundering.

The agency also penalized the bank for failing to ensure adequate oversight and compliance policies. The documents said the bank’s failure to report outgoing and incoming electronic funds transfers has a high impact on FINTRAC’s ability to fulfill its mandate “to detect and deter money laundering and terrorism financing.”

The sheer volume of unreported transactions is “shocking,” said financial expert Richard Leblanc, a professor of corporate governance at York University. It pointed to the possibility of bank employees conspiring with the client to hide the money from authorities, he said in an interview.

“This is a remarkable failure of governance at a major financial institution,” said Leblanc. “It's shocking that this would occur.”

Bankers decline to comment on new information

The Canadian Bankers Association, an industry lobby group that represents Canada's banks, declined to comment on the new information, referring National Observer and the Star to what it said eight months earlier when the $1.15 million penalty was first announced. That statement said that banks in Canada had a "strong track record" of complying with money laundering and terrorism financing legislation.

The lobby group is now in the midst of running an ad campaign that encourages Canadians to trust their banks.

Adam Ross, who authored a recent report on money laundering in Canada for Transparency International, said the case highlighted the total lack of due diligence.

“It’s either systematic collapse of a monitoring system or employees of the bank were aiding and abetting this guy.”

FINTRAC could not respond to whether Strempler was the bank’s client, citing the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorism Financing Act. However, the dates and descriptions in the documents line up with Strempler’s activities:

- The FINTRAC documents say the client was arrested in June 2012, “following his deportation from (censored).” Strempler, according to news reports, was arrested in Miami in June 2012, during a stop over on his deportation flight from Panama back to Canada.

- The FINTRAC documents say the client pleaded guilty in October 2012, “related to the commission or attempted commission of a money laundering offence.” Strempler, according to court documents, pleaded guilty in a Southern District of Florida court on Oct. 4, 2012, to “conspiracy to commit mail fraud and wire fraud.”

- The FINTRAC documents say the bank was aware of an FDA investigation into the client in 2011. On Sept. 8, 2011, a FDA investigator “confirmed” to the bank that, “there was an active investigation of (censored).” Strempler’s factual proffer, signed Oct. 8, 2012, states the FDA sent him a letter as early as 2001 saying, “it would be illegal for RxNorth to ship drugs that were not FDA approved into the United States.”

- The FINTRAC documents say the client was sentenced in January 2013. Court documents show Strempler was sentenced to 48 months in jail and fined $25,000 by Judge Jose E. Martinez on Jan. 9, 2013.

Strempler was transferred to a minimum security prison in Manitoba in July 2015 and was released in October last year. His name now appears on a consultancy firm based outside of Winnipeg. Strempler did not respond to repeated requests this week for comment.

In addition to the secrecy surrounding Strempler, FINTRAC has refused to name the bank. Sergeant Harold Pfleiderer, an RCMP spokesman, told National Observer and the Star in an email that the police force could only comment on an investigation if charges were laid.

In the documents obtained by the Star and National Observer, FINTRAC lays out three criteria for public naming, saying it will disclose names if one of the conditions are met. The unknown bank appeared to meet at least two of the three criteria — it committed a “very serious violation,” and its penalty was greater than $250,000. The third criteria would also be met if FINTRAC concluded there was "repeat significant non-compliance on the part of the person or entity."

The documents released by FINTRAC also confirm that the agency determined that the entity qualified for public naming.

However, in its response to the access to information request, which took eight months to produce, FINTRAC censored information about the bank citing sections of the Access to Information Act that allow government organizations to withhold information that could harm the reputation or business interests of a third party.

National Observer has asked Canada's information commissioner, Suzanne Legault, to investigate FINTRAC's censorship of the documents that were released through access to information legislation.

Leblanc: Bank anonymity is 'un-Canadian'

Ongoing anonymity around the bank involving such a large-scale financial breach is “un-Canadian,” said York University’s Leblanc.

“Normally, in a country like ours, there's disclosure and transparency,” he said. “You can't have deterrence without names. That's the most important thing — the name of the institution and individuals involved… There's a public right to know.”

Richard Powers, director of governance programs at the Rotman School of Management at University of Toronto, added that corporations found guilty of wrongdoing should face the same public accountability as individuals.

“If it were me, the name would be on the front page,” he said. “Any person would be identified. Why should a corporation not face the same? To act as a deterrent, there should be full disclosure.”

The bank’s infractions — which included failing to develop and apply compliance policies and procedures — did not prompt criminal charges because FINTRAC determined, “an administrative monetary penalty was the most appropriate course of action.”

In the documents, Fintrac describes the STR reports as “the most significant report that Fintrac receives as it conveys information directly relevant to money laundering or terrorism financing.” Failing to file an STR constitutes a “violation with the most impact.”

The unreported deposits and transfers of sums $10,000 and beyond constitute a violation at the “foundation of the regime which is reporting of transactions to FINTRAC,” reads the reasons for decision.

Strempler was already facing fraud related charges in the U.S.. The bank had frozen his account, filed two previous “suspicious transaction reports” (or STRs) and placed him on “enhanced monitoring” which included filing to FINTRAC on a quarterly basis about his activities.

“High volumes of wire transfers were received in the client’s account and the transactions involved a potential shell company,” the FINTRAC analysis document reads. “The transactions involved (censored) which is known or suspected to be a country facilitating money laundering activities and a country where illicit drug production or exporting may be prevalent.”

The bank appears not to have challenged FINTRAC’s findings, according to the documents. FINTRAC’s list of reasons for its decision says, “FINTRAC’s determination that a violation occurred is not contested.”

At another point, the documents say, the bank “admitted to the violation by stating that it should have reported the (suspicious) transaction in question (from February 2012) as a suspicious transaction.”

In a letter to the bank on Dec. 15, 2015, an unnamed FINTRAC official wrote that the $1.5 million figure “was reviewed in light of the written representations you had submitted” and that “after full consideration…I impose a total administrative monetary penalty of $1,154,670.”

Those bank submissions, filed Sept. 30, 2015, argued the proposed penalty was, “too high in consideration of the nature and actual circumstances of the violations,” and that “the harm done … is minimal.”

FINTRAC imposed the penalty Dec. 15, 2015 but did not make its first-ever fine against a bank public for more than three months.

— with files from Juliet O'Neill

Editor's note: This article was updated on March 1, 2017 to correct details regarding some of the violations and clarify that not all were related to one individual client. This correction was made following comments made by the bank which publicly identified itself on Feb. 27 and provided additional information about the case.

Comments

Well, well, well...quelle surprise! A major Canadian bank repeatedly breaks the law and ends up with a quiet little slap on the wrist to reinforce the view that the worst that can happen is a paltry fine, just another cost of doing illegal business. It would be naive to believe that this was/is the sole example of knowing money laundering, it's just one that surfaced. In the pursuit of maximum profit the only gauge of success is maximum profit, not how it was achieved.

Even if the officials do not think that they could win a case involving "intent" in a court of law, they should still reveal the name of the bank to the public. The fact that they fined them over a million dollars suggests that they know there's culpability on the part of the bank - and publishing their name would at least bring about some well-deserved embarrassment and shame to it.

The fine is paltry compared to the offence. For it to be a deterrence, the fine should be much larger than the amount of the offence, but that requires a change in the rules. Meanwhile the bank should be named so that the public can let the bank know how it feels about such activity, perhaps by not dealing with it. Until then all banks are suspect, and the other banks should not like that.

I could not agree more with other comments posted about naming the institution involved, their methods and how they base their success. Further to this, I would add that corporations are seen as "persons". With this being the case, as stated in the article, a person would be named. So if corporations have the same rights as people, and banks are incorporated, then they need to be named. This is within FINTRAC's power. So if they are withholding the name, why? And can they be forced to name the bank?

How much did this bank donate to the Liberals over the last 10 years to buy such blatantly preferential treatment? This is just the laws broken for ONE client! The fine is probably less than their quarterly doughnut expenditure. Like KPMG, they are far too cozy with beaurocrats and are considered too big to punish, lest it rattle the ponzi banking scam.

Shareholders and potential investors need to know the name of the financial institution in question. The fine reduces the bottom line of financial performance. The mismanagement, or culpability if the activity was intentional, shows the management quality and reliability of the corporation. Name disclosure is required for the integrity of information for stable and reliable financial markets for Canadians and for international investors.

Some of these financial institutions should just have their entire operations, all their assets, seized as the "proceeds of crime" and then nationalized. Maybe that would make some of the others think twice about some of the nonsense they pull.