Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

This investigation was reported by Trevor Jang for Discourse Media. It is the second part of an ongoing investigation into how government negotiates with First Nations for major resource development projects. Read the first part here.

Nestled in the forests of northwestern British Columbia, Richard Wright hauls a 30-pound moose chest out of a smokehouse. He shot the animal a few days ago, just a few kilometres north of camp.

“You want your wood to smoulder, not flame or get too warm. So you either get some alder or some cottonwood, which changes the flavour that you’re adding to the meat,” Wright says, after placing the chest in the back of his trunk, followed by the legs, rump, backbone and spine.

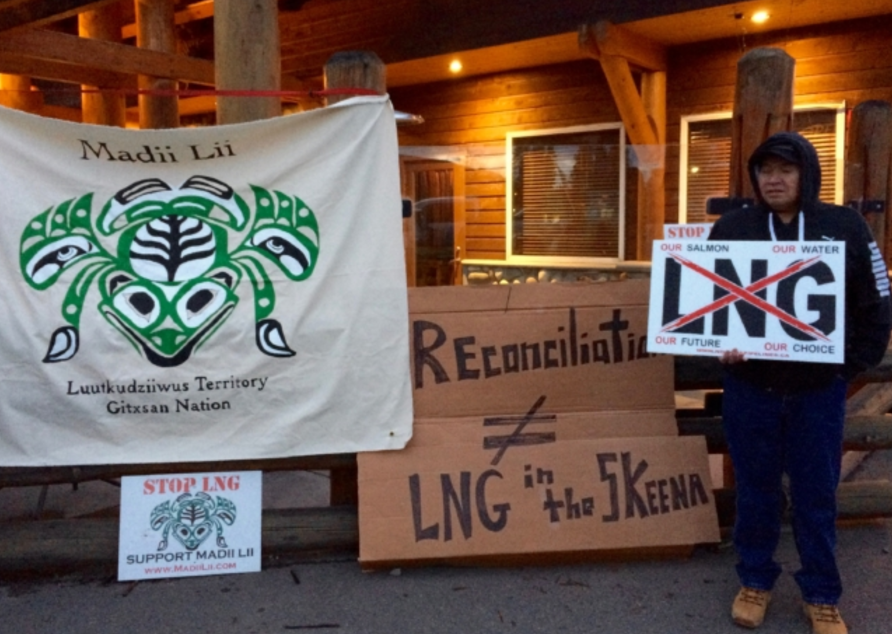

Wright is preserving food in the way the Gitxsan people here have for many generations. The act also has a deeper purpose; this camp, where he and others are living off the land for the past two years, is a form of protest, an occupation of a sort. The Madii Lii camp, which includes a cabin, smokehouse, greenhouse and garden, strategically blocks the path of the proposed Prince Rupert Gas Transmission (PRGT) pipeline. The 900-kilometre pipeline is proposed to carry natural gas from northeastern B.C. to the Pacific NorthWest LNG (PNW LNG) export terminal proposed for Lelu Island on the province’s north coast.

Wright is a member of the Luutkudziiwus, a traditional “wilp,” or house group, of the Gitxsan Nation. The nation is made up of more than 50 wilps, organized into four clans. The wilp is the central and most important social unit in Gitxsan culture. But these traditional wilp groups aren’t just symbolic — they carry political and legal weight too. Led by a hereditary chief, each group has authority over a specific chunk of “lax yip,” or traditional territory.

Wright is opposed to the LNG pipeline because he’s concerned about the environment, especially the risks the project poses to the region’s salmon population. But not all First Nations or Gitxsan people are against the project.

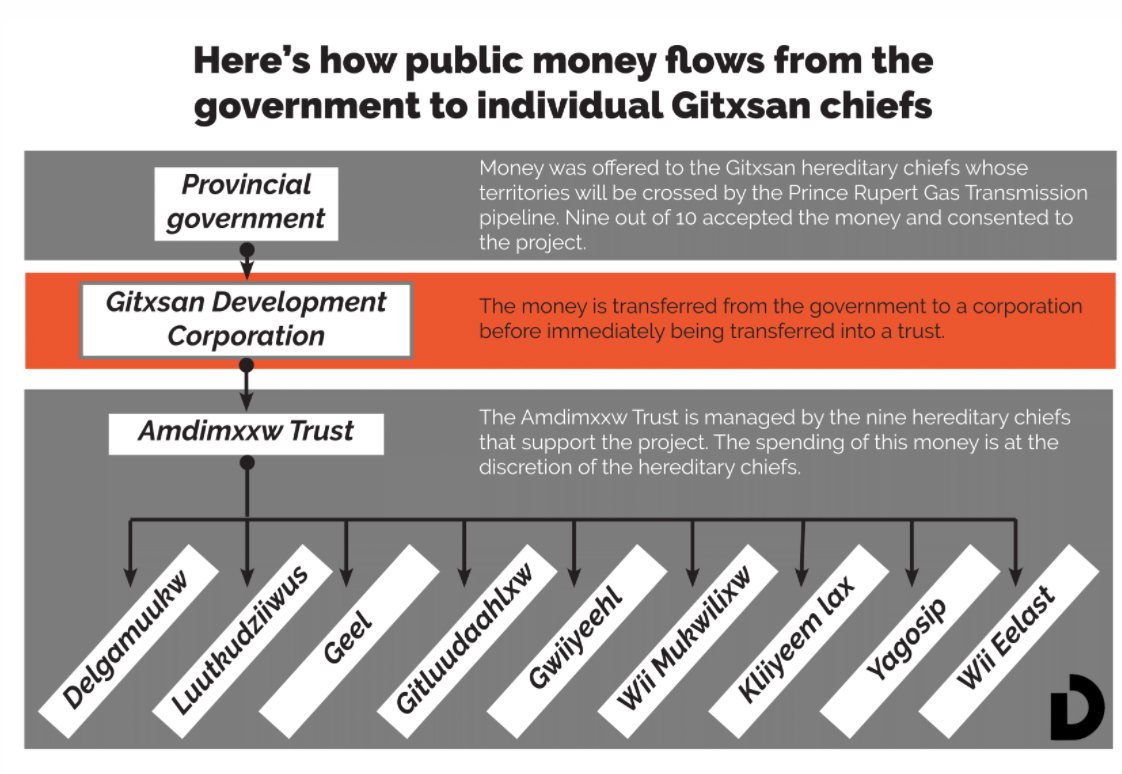

In the fall of 2016, a small group of Gitxsan hereditary chiefs secretly signed an agreement approving the project on behalf of the entire Gitxsan Nation. The group is made up of chiefs whose lax yip is directly crossed by the proposed pipeline route. They accepted millions of dollars in exchange for their support of the project. Since the deal was made public when documentation was leaked to the community late last year, the chiefs have stated publicly and in interviews that the money would help support development in a region plagued with unemployment and poverty.

Wright’s main concern is that a man named Gordon Sebastian signed as a hereditary chief on behalf of the Luutkudziiwus wilp. Wright claims Sebastian did so without consulting the wilp members. He also says Sebastian shouldn’t have been signing in the first place because he’s not their chief at all. Wright is now attempting to stop the project in court. He says the provincial government and PRGT have been negotiating with the wrong people and sparking conflict in the community.

Internal conflict over who has the authority to speak for the entire nation when it comes to considering resource deals is not unique to the Gitxsan. Some critics say that the B.C. government, which has a legal obligation to consult First Nations when developing deals, fuels and benefits from internal division by negotiating behind closed doors only with those individuals who are likely to say yes. They argue that the government appears afraid to seek informed consent from the nation through a consultation process that is inclusive of all members.

How this conflict unfolds will not only influence the fate of one major LNG project — it could forever impact the way the Gitxsan Nation governs itself.

Traditional values versus economic needs

Wright and Sebastian agree on at least one thing. Many Gitxsan people live in poverty. According to a report from the Gitxsan Treaty Society (GTS), unemployment rates on Gitxsan reserves are between 60 and 90 per cent. For Sebastian, executive director of the GTS, addressing this immediate economic need trumps the potential environmental risks of the LNG project.

“We have people 50, 60 years old that are still living with their parents. They’re pretty hard to employ. They have a hard time passing basic little exams to determine whether or not they could be employed,” says Sebastian. “But we cannot ignore them.”

In a region that struggles with economic development, the PNW LNG and PRGT projects promise to bring thousands of jobs to northern B.C., including at least 200 jobs for Gitxsan members. Sebastian says those jobs will mainly be clearing bush and trees for the pipeline, working in work camps, and providing safety and security services. In addition, he says the hereditary chief's business arm, the Gitxsan Development Corporation (GDC), has already provided skills training for 160 people.

GDC director Rick Connors says the corporation has become the largest employer in the entire area, employing more than 110 people at peak times this past year. He estimates they’ll gross more than $20 million in 2017.

“We heard testimony from some of our staff ... that the suicide rate has come down in the area. We’ve made a tremendous difference in the area because we’ve now brought some economic hope,” says Connors.

But the occupiers of the Madii Lii camp don’t believe the economic benefits of the projects are worth the environmental and cultural risks they pose. They are focused on protecting the salmon that swim through a series of rivers in Gitxsan territory and eventually end near the proposed site of the PNW LNG terminal on the coast.

“We are in an economically challenged area where we’re primarily more focused on protecting our environment and way of life [than on] joining a huge industrial development that could potentially leave lasting negative impacts to our land,” says Wright. “Our nation relies upon the salmon to subsidize our food and sustain us.”

How was the pipeline decision made?

The PNW LNG project received conditional approval from the federal government in September 2016, with 16 First Nations along the PRGT pipeline signalling their support for the project. These communities are positioning themselves to receive millions of dollars in financial benefits. At the time, the Gitxsan were not publicly among them.

Less than a month later, however, a pair of confidential documents were leaked into the community, revealing that, much to the surprise of many Gitxsan people, they were included among the First Nations supporting the pipeline.

One document, the “Prince Rupert Gas Transmission Project Natural Gas Benefits Agreement,” says the B.C. government will provide the Gitxsan Nation with nearly $6 million at various stages of construction in exchange for the nation’s support of the project. The other document, the “Trustee Resolution of the Amdimxxw Trust,” states how much each individual chief who signed on is distributed.

Sebastian’s share? More than $500,000. But that money, he says, is for all Luutkudziiwus wilp members.

“If we divided the funding up per person, each person would be entitled to about $1,100. So I asked each members that I speak to, ‘Do you want that? Or do you want to keep it together so we can invest or do something valuable?’ And they would rather keep it in an account until we all decide how to disburse the money,” he says.

However, some Luutkudziiwus wilp members are upset Sebastian didn’t consult with them before signing on their behalf.

The leaked agreements were left on the doorstep of Richard Wright’s sister Pansy Wright-Simms, who is also a Luutkudziiwus member. She immediately uploaded photos of the documents to Facebook, sparking over 100 comments and shares from people expressing shock and disapproval.

“The information was just mind-blowing to me,” Wright-Simms says. “People were clearly upset that nine individuals could speak on behalf of our entire nation. “We clearly haven’t consented to this.”

Shortly after the documents were leaked, the chiefs who signed the agreement released an information package to members. It outlines the benefits of the agreement and explains how the chiefs came to their decision. It describes a four-year process that included more than 45 meetings with PRGT, the provincial government, industry experts, and those opposed to the project. But that process doesn’t mean that chiefs had a mandate from their communities or the Gitxsan Nation to sign the agreements.

'Why do I have to consult with them?'

Darwin Hanna is an Aboriginal lawyer with expertise in First Nations land rights. While not speaking specifically about the Gitxsan, he stresses that First Nations leaders have a duty to inform their own people.

“First Nations generally have a fiduciary duty to make sure the membership is fully engaged and provided with full information prior to making any decisions that may affect the way of life,” he says. This duty was confirmed in the landmark 1997 Delgamuukw court case, where the Gitxsan went all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada to fight for their legal right to the land — and won. The case also confirmed that Aboriginal land rights are held communally, which means that decisions regarding the land should be made communally.

“The issue here is: Has the leadership taken certain measures to provide for informed consent?” says Hanna.

When asked about consultation with wilp members, Sebastian says, “I indicate to the people what I’m doing. They know that I’m involved with this pipeline. Nothing happens on Gitxsan territory without people knowing.”

Sebastian believes that the hereditary chiefs have the authority to make decisions regarding the land on behalf of their members. “If somebody wants to cross the territory, they speak to the head chief. If you want to camp there, you speak to the head chief. If you want to build a pipeline, you speak to the head chief.”

So did Sebastian consult with his members? He says, “Consultation has happened. We did it from the point of view of our ayook [traditional Gitxsan law]. And we felt we did a very good job.”

The Luutkudziiwus have approximately 600 wilp members. When pressed about exactly how many of those members Sebastian consulted before signing the agreement, he says, “Probably around 10.”

And what did consultation with those 10 look like? Sebastian responded, “I don’t understand what you mean. Why do I have to consult with them? It’s the government’s obligation to consult, and they consult with me as a representative of the 600 people.”

Expert says government scared of informed consent

Jacob Beaton is a former communications consultant who spent more than 15 years assisting B.C. First Nations with engaging their members leading up to difficult decisions. He says uninformed membership is a common problem in pipeline negotiations. He places blame primarily on the pipeline companies and the provincial government.

“The problem is that there’s a lot of opposition from proponents and governments to inform people because they’re terrified of a possible ‘no.’ So rather than do any effort to inform people, they just say, ‘Let’s do a confidential agreement and forget about informed consent,’” he says.

Beaton has been trying to help the community make sense of the agreements since they’ve been leaked. He’s Tsimshian, not Gitxsan, but he grew up and resides locally in Hazelton, B.C., which is in Gitxsan territory. He says the B.C. government continues to create community backlash by pressuring leaders into signing agreements without first gaining a mandate from their members to do so.

“I’ve been in the room where First Nations have been saying, ‘We need some money so we can inform our people.’ And the government representatives have said, ‘No, just sign, then take the money and inform your people.’ How backwards is that?”

A representative from the provincial government responded to these claims in an email, writing that “government provided the opportunity for consultation on the Prince Rupert Gas Transmission project to Gitxsan hereditary chiefs whose house territories could potentially be directly affected by the project, as well as any other interested Gitxsan hereditary chiefs — and many expressed support for LNG development.”

The response did not directly address the claim that government representatives advocate confidentiality with individual First Nations leaders out of fear of getting a “no” from the community at large.

As for PRGT, when asked how they consulted with the Gitxsan on the project, a representative wrote in an email, "TransCanada [of which PRGT is a subsidiary] has a robust engagement policy that guides all of our interactions with Indigenous communities. As a result of those interactions, PRGT has been able to sign benefits agreements with 13 First Nations along the route. This demonstrates that our approach works."

The traditional approach to business

Pansy Wright-Simms says that in Gitxsan tradition, a business decision of this magnitude would be decided communally in the feast hall. All chiefs and wilp members would gather and have their voices heard. The meeting would go all night, and the chiefs would walk away with a mandate from the people to either negotiate or oppose the project.

“If government or industry wanted to do any business on our territories, they should be doing the business in our feast halls. They have to remember they are visitors here. These agreements are happening because they know they need consent of the first peoples of these territories,” she says. “What’s said in our feast hall is our law.”

Wright-Simms says that didn’t happen with the PRGT decision. Instead, the agreement was negotiated through closed-room discussions. But GDC director Rick Connors, who led the negotiations on behalf of the chiefs, says draft agreements needed to be kept confidential in order to maintain leverage in negotiations.

“We had to have these very closed-room discussions about these sort of things because that’s just the way these negotiations are. You don’t disclose your position to the opposite party while you’re negotiating a contract and expect that you’re going to get success if you do do that,” he says.

His view clashes with that of Wright-Simms, who says she is fighting for the Gitxsan to return to the way previous generations did business, which was communally. “I really feel sick that we’re falling into their system and their way of doing business. Because our business is traditional,” she says.

George Muldoe is an elder from the Delgamuukw wilp. He sees the recent conflict as a sign that the Gitxsan are losing touch with their traditions. “Personally, I think we’re in dire straits because every time I go to a feast, I look down the table and there’s nobody there you could trust,” he says.

Muldoe, a residential school survivor, says Gitxsan culture isn’t being passed on to younger generations. “We’ve got four cabins and nobody goes out there. Nobody’s learning the territories. They don’t know our boundaries. I’m really afraid of it. There’s no interest,” he says.

As an outsider looking in, Beaton acknowledges that the governance issues facing the Gitxsan are complex. There are more than 100 chiefs at any given time, all trying to make decisions. Some support LNG development, some don’t, and some don’t know. Beaton says the divide and the complexity within the Gitxsan Nation have frustrated both government and industry who want to develop projects across Gitxsan land.

“The feedback I hear is that the Gitxsan government situation is a disaster. I’ve been in rooms where the Gitxsan are a bit of a joke, to be frank,” he says.

But what’s not funny is the result of this so-called disaster. With no clear communal decision-making process in place, Wright-Simms believes government and industry end up negotiating behind closed doors with whoever is most likely to say yes to development. And she points her finger squarely at the man who signed on behalf of the Luutkudziiwus wilp: Gordon Sebastian.

“He does not have the authority or the consent of our house group to represent our interests as he is not our chief,” she says.

Who speaks for Luutkudziiwus land?

In Gitxsan law and culture, a chief's name is passed on one year after the previous holder of the name dies. This is done in the feast hall with witnesses present.

But when the previous hereditary chief Luutkudziiwus passed away, both Charlie Wright and Gordon Sebastian held settlement feasts to take the Luutkudziiwus name. The Wrights say one feast was held for Charlie first, and that Sebastian held one shortly thereafter. The Wrights say the wilp elders chose Charlie to lead, while Sebastian says his uncles chose him.

“As a hereditary chief, I cannot put Charlie down. I respect him,” says Sebastian. “But you have to take a look at Charlie. He’s quiet. He never speaks up publicly. He never challenges me publicly. He never challenges me in the feast hall.”

But when asked, Charlie Wright says that Sebastian does not represent the wilp. “These names belong to the house. Gordy did this on his own. He does everything on his own.”

On Jan. 10, 2017, the Wrights, representing the Luutkudziiwus wilp, joined with members from the Gwininitxw wilp to file a court action in an effort to stop the project. They hope to have the federal government’s approval of PNW LNG overturned on the claim they were not properly consulted.

Meanwhile, Richard Wright, Charlie Wright's appointed spokesperson and a distant cousin, has been gathering signatures of wilp members who support Charlie Wright over Sebastian. So far, he says, he has gathered 30. He says what scares him the most about the pipeline agreements is the precedent they set: that a chief can make a decision regarding the land without consulting the wilp group.

“They are making it so that the chief is the only one that you need to talk with or pay off and that has never been the way it is. A chief takes his direction from the entire house group. The chief name belongs to the house group. The lands and resources are under the authority of the house group,” he says.

Restoring communal decision-making

Beaton believes that the Gitxsan have the ability to get their governance back on track.

“If Gitxsan really want to change things, they can do it. But the different factions need to stop ignoring people. [They] need to actually go and comprehensively have a conversation and find out what their people want and where the lines need to be drawn,” he says.

While the Luutkudziiwus wilp and the Gitxsan Nation are struggling to work through internal division over how decisions are made and who can speak for the people, the government has a signed agreement saying that the entire Gitxsan Nation consents to the project. The process has left many people in the community feeling ignored, and it remains unknown what Gitxsan members actually want.

Beaton calls this a “terrible process,” imposed by governments and industry when they want to build major projects across traditional territories. He says that if the province was willing to advocate for and support First Nations in establishing their communal decision-making processes, everyone might get what they want in the end, without backlash from members.

“The fact is, if most Gitxsan people were informed of the impacts and collective benefits to development, I believe a majority would say yes. Why? Because people here are economically destitute. There are a lot of empty fridges. It’s a real thing.” Beaton says.

“We have kids that show up to our door hungry, and we feed them. They come at the end of the day and they haven’t had a meal all day long. Most of my kids’ friends are Gitxsan, and most of their friends are hungry every single fricking bloody day.”

Comments