Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

The other day, I received an email from the US National Council for Science and the Environment, calling for “evidence-based policymaking” to support “high-functioning” societies. “Unbiased and apolitical science,” they argued, “is critical to a healthy and stable democracy.”

Until recently, such a declaration will have been unremarkable. But when “post-truth” and “alternative facts” become the norm in socio-political discourse, the NCSE’s point becomes particularly noteworthy. As we lose faith in the word of politicians, there is growing mistrust in institutional and societal stability. Social media’s “homophilous sorting” ensures that information is distributed to like-minded clusters as contemporary scientific realities are shaped, distorted, manipulated and disbelieved.

In that setting, the NCSE’s message serves as a pointed reminder of the importance of providing compelling reasons and justifiable, scientific evidence in support of decision making around the common good.

Yet, the problem remains: how do we ensure that high-integrity scientific truths genuinely inform public policy? In fact, what constitutes compelling evidence-based knowledge today? As governments are pressured to make decisions around huge issues, from the construction and expansion of pipelines to carbon taxes, how do we enable scientifically-knowledgeable policy decisions?

There is good reason to turn to universities for help. In 2014 alone, universities supported $13 billion in research and development, educating more than 1.7 million students and driving innovation. Universities serve as our most reputable centres of in-depth, high-integrity peer-reviewed research. The expertise is there; governments should use it.

To enable better connections, universities themselves need to identify those academics who are stellar researchers who also have the capacity to translate their work into non-specialist language. (Not all do.)

As a dean, I have a good idea as to who those researchers might be in the built and natural environment fields. If a Minister were to ask me to suggest someone who can speak to energy or transportation or science policy in a lucid, compelling manner, I would know who to suggest, both within my university as well as elsewhere across the country in some cases. Designing a searchable research database – a project in progress within my own Faculty – will only help to facilitate that identification process.

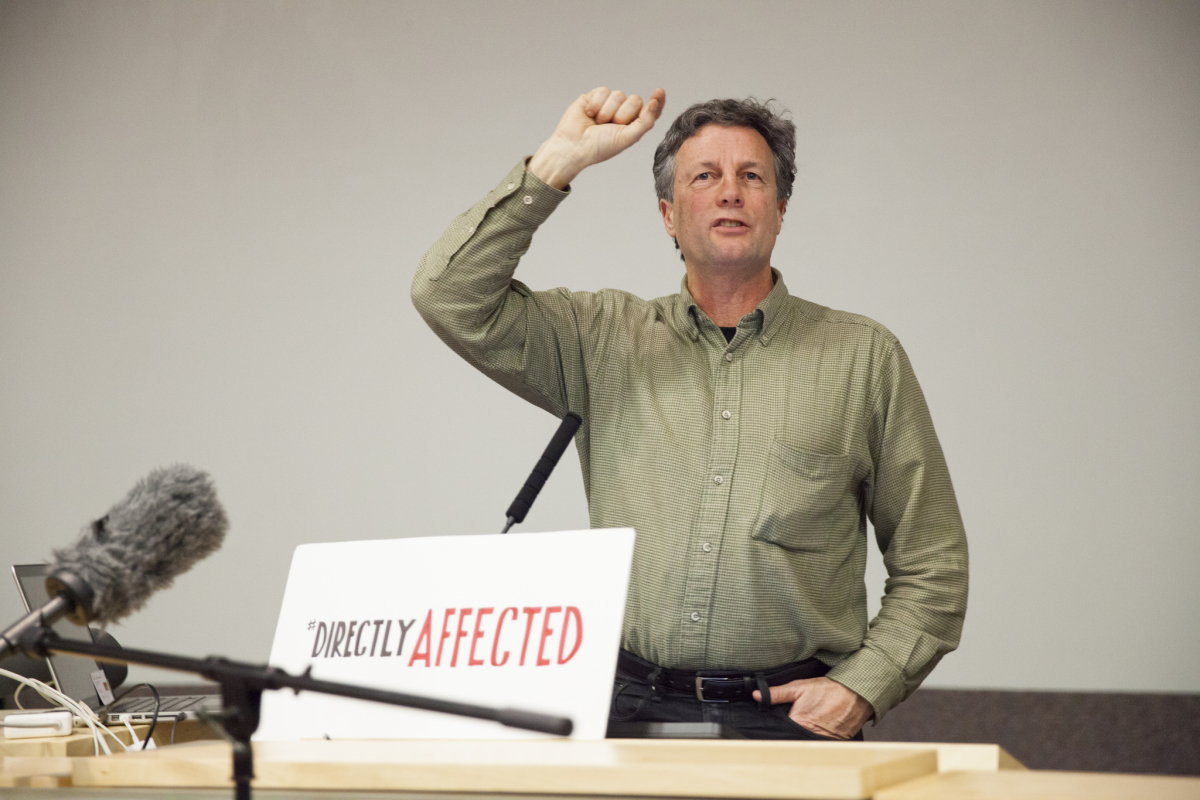

Government themselves should turn to universities to identify members of specialized advisory groups. The now-defunct National Round Table on the Environment and Economy (NRTEE) is a case in point. Their mandate was to bring together intellectual leaders to recommend “constructive policy actions and enable changes in our communities.” Former NRTEE member Mark Jaccard reflects how “the reality of public policy-making in today’s polarized and partisan politics is that the real action is behind closed doors, not in public hearings and advisory body reports.” Yet, if policy making is to be transparent and scientifically justified, an advisory council on the environment and the economy should be reconstituted. The power of expert advice is exemplified when 96 per cent of participating scientists collectively conclude that climate change is anthropogenically-caused, as happens through the work of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. As Jaccard points out, ““if the government really does want open public input – perhaps to justify something that is difficult – then a body like the NRTEE can be valuable.”

Even when apparently objective, scientific “truth” seems to be available, there are other human factors that complicate a simple linear process that easily moves from science to policy. Life is messier than such a linear process allows. Much contemporary decision making – particularly around such “wicked” issues as environmental challenges – is imbued with complexities and plural narratives. The construction of a pipeline, for instance, will impact multiple community interests. From indigenous to corporate to ecological concerns, scientific analysis of environmental impacts will not necessarily guarantee “the truth” in any absolute sense.

But it is high-integrity academics – particularly interdisciplinary groups – who can bring clarity and intellectual insight to the table, ensuring that pollsters do not have the freedom to distort and discredit growing scientific consensus around issues like climate change in an age of “post-truth politics.”

Other collaborative models exist to bring government and universities into a closer working relationship. In the United States, collaborative research institutes bring together government scientists, policy makers and academics within shared labs and office space. In my faculty, such an institute is home to scientists from the Department of Fisheries and Oceans who supervise graduate students and interact with them and other faculty members on a daily basis. The immediacy and regularity of such interaction opens the door to research that is informed by government priorities as much as by intellectual curiosity.

Finally, universities should be urged to include not only discovery research but high-integrity, community-engaged research as well. Multiple stakeholders - municipalities, provinces, the federal government, indigenous groups, NGOs, corporations, industry and other community members – may themselves identify priorities that inspire new academic research. Within our Faculty, innovative studies have emerged directly from community workshops and dialogue sessions which help to identify academic priorities, from the scientific study of sea lice on juvenile salmon to the production of raingardens to control for flooding in cities.

To be sure, it is universities themselves who need to position themselves to move out of their ivory towers and they are already doing so, sometimes more in some institutions than others. But we can all do more. Governments need to be regularly reminded to take advantage of the enormous research expertise that defines the academic mission.

And universities need to be reminded that genuine intellectual curiosity can be inspired and aroused through projects that are ultimately policy-relevant.

Ingrid Leman Stefanovic is a professor and dean from Simon Fraser University's Faculty of Environment.

Comments

I applaud the idea of multi-disciplinary group doing science research. One area that could benefit is marijuana consumption and the legal, medical, social consequences all impact on the laws and understanding of this plant. A medicinal plant for thousands of years and only in the last 70 or so has it been a pariah and forbidden. Since pharmaceutical companies cannot patent it, they are working on teasing it apart so they can tweak something and then patent the tweak. It would be great to have research on the effects of the many constituents of the whole plant on pets and humans. Currently, there is both an epidemic of health issues that might be treatable by it and an epidemic of self-users trying it out blindly on their own as they seek a way to stop pain or cure/reduce impact on them of incurable diseases.

Any research would need to be funded by resources other than mega companies who often like to skew the experiments and results to findings conducive to their bottom line.