Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Only a few days into his new job as an executive at Canada’s energy regulator Sylvain Bédard asked for help.

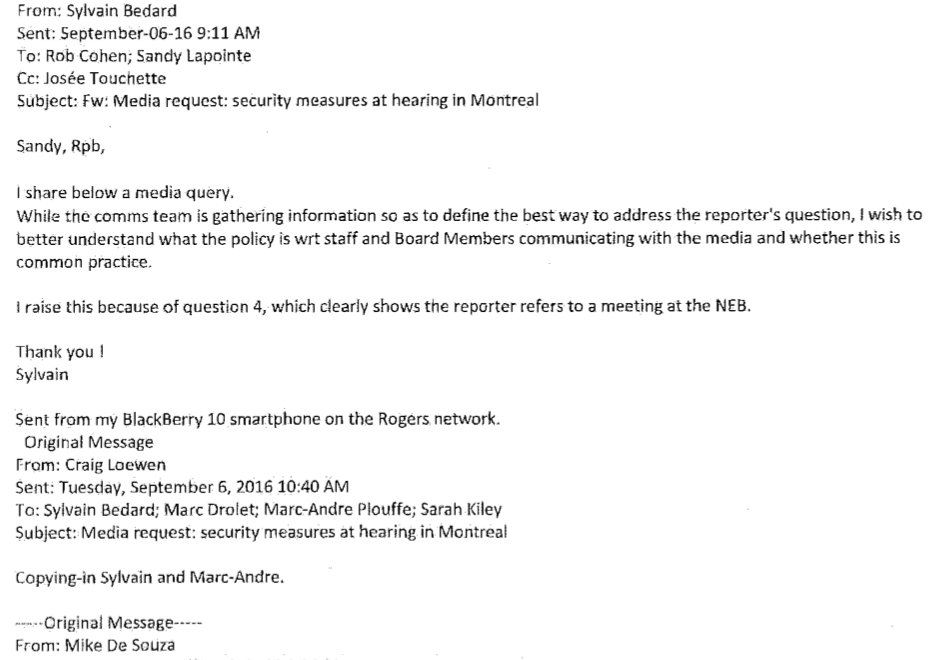

A list of six questions from National Observer had arrived in his email inbox.

Most of the questions were about botched security arrangements for a National Energy Board (NEB) pipeline hearing in Montreal.

One of the questions described a verbal blunder by Bédard's new boss, Josée Touchette. The gaffe had occurred during an Aug. 30 town hall meeting at the NEB's Calgary headquarters, staged to brief NEB employees after a protest had disrupted the Montreal hearing. Touchette had joked about tasering environmental activists.

National Observer's reporter — this reporter — wanted to know why.

What followed was an investigation by the NEB into who told National Observer about Touchette's joke. This investigation will cost the federal government $24,150.

"It's a witch hunt," Ian Bron said. Bron, a former whistleblower who denounced wrongdoing several years ago in an unrelated case at Transport Canada about marine security, is familiar with how this works.

All of this was triggered in early September 2016 with the pipeline regulator engulfed in a conflict-of-interest scandal. The NEB was also battling criticism that it was too cozy with the oil and gas industry and could not be trusted to protect public safety and the environment.

The regulator told National Observer it launched the investigation to defend against a "security risk." But the evidence emerging indicates something else entirely.

Former whistleblowers like Bron interviewed by National Observer for this story said they recognized a pattern of intimidation. They said it appeared the regulator was trying to impose a code of silence on employees to discourage them from questioning misconduct by management.

Mobster mentality at the NEB

Bron, is an advisor at Canadians for Accountability, an organization whose mission is to support whistleblowers. He didn't mince his words when asked to describe what was happening.

“The real message they want to send out is, 'if this happens again, we’re coming for you'. It’s a kind of mobster mentality," Bron said.

“Criminal enterprises can’t survive if there’s transparency... and this (is an) idea that you have to shut up people who are speaking out and do it in a way that sends a clear message of intimidation…It (the message from NEB management) is not as far on the spectrum of course, but it’s in the same ballpark.”

After Bédard reviewed the six questions from National Observer, sent on Sept. 6, 2016, he fired off an email to three executive colleagues, including Touchette, the chief operating officer and top bureaucrat at the NEB.

The questions revealed that the reporter knew what took place behind closed doors, Bédard wrote in the email.

Bédard was new to the scene at the NEB. He had just been recruited over the summer, leaving a position at Quebec transportation company Bombardier. He accepted a newly-created position at the pipeline regulator as executive vice-president of transparency and strategic engagement. This followed his previous role in the public affairs division at the Department of National Defence where Bédard had worked with Touchette.

Bédard explained, in the email he wrote to his executive colleagues, that he wanted to “better understand” what the NEB’s policy was regarding staff and Board members who speak to the media. He asked whether it was "common practice" for employees to speak to reporters.

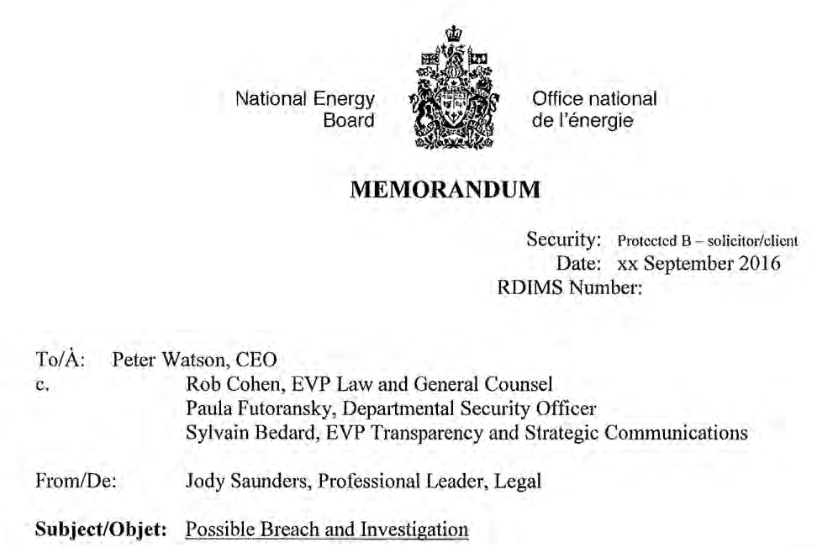

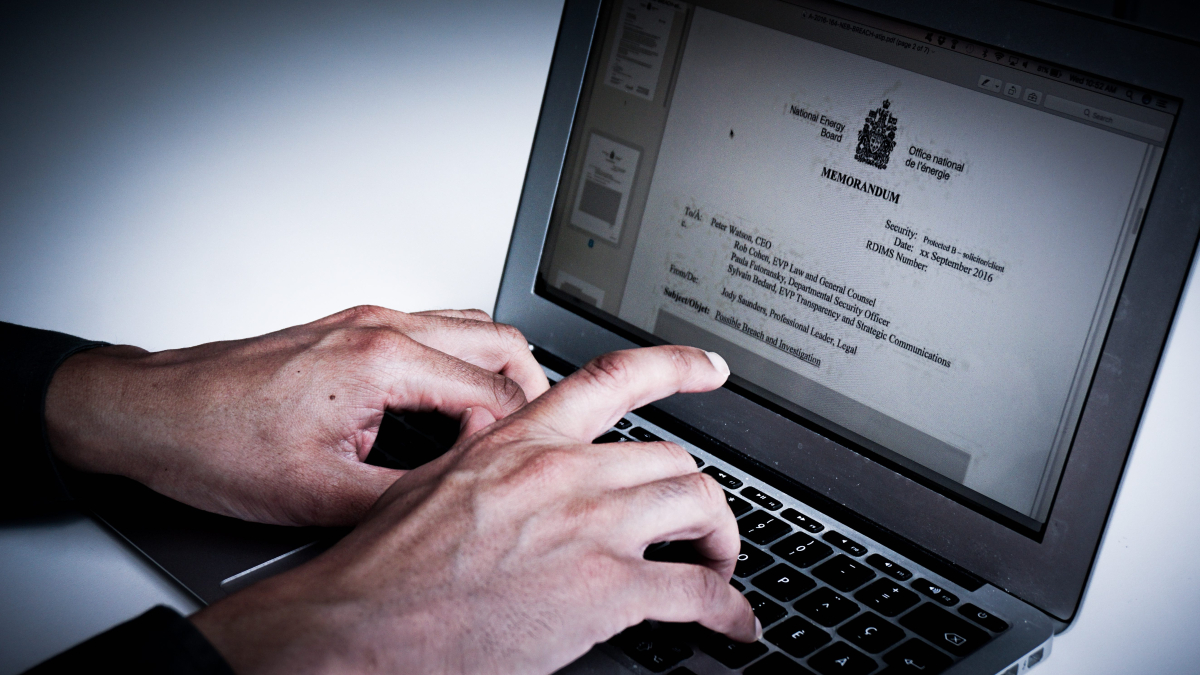

Three days later, on Sept. 9, the regulator's lawyers sent a draft memo to NEB chairman and chief executive Peter Watson about a "possible breach and investigation."

This was no ordinary day at the NEB.

Several high-ranking members of the Board, including Watson, announced on that same day they were recusing themselves from involvement in the review of the Energy East pipeline proposal. Energy East is a 4,500 kilometre crude oil pipeline proposed by Calgary-based energy company, TransCanada Corp.

The recusals were unprecedented. After admitting to an appearance of bias, four NEB members removed themselves from participation in any decision-making about Energy East. Evidence that was also revealed by National Observer in a series of reports in July and August had triggered the recusals. At the same time, the investigative reports also forced the NEB to apologize for making false and misleading statements about a private meeting that its high-ranking officials had with a TransCanada consultant, former Quebec premier Jean Charest.

A few days after those recusals, on Sept. 12, the NEB said the memo from the legal department about the "possible breach and investigation" had been discussed internally at the regulator.

This memo was later released to National Observer through access to information legislation, but the NEB censored the entire contents, apart from the subject line that read "possible breach and investigation," along with a few names of the executives such as Watson, general counsel Rob Cohen and vice-president of transparency Bédard.

By Sept. 20, the NEB had signed the $24,150 agreement with Ottawa-based Presidia Security Consulting to assess the situation and investigate whether any of the regulator's employees were speaking with reporters. Bédard was listed as the "responsible authority" for the contract.

National Observer obtained a copy of the contract through access to information legislation. It said that Presidia was required to discuss its initial findings with Bédard and prepare a preliminary assessment for Watson, the chief executive. Following that, Watson could direct Presidia to launch a full-blown investigation to identify the whistleblower. Such an investigation would also require Presidia to gather names of "witnesses," interview them and provide an explanation if anyone who was named as a witness, could not be interviewed.

Less than two months later, Bédard warned employees that whistleblowers were a "security risk" and said an investigation was underway.

“Earlier this year, it came to the attention of the NEB’s leadership team that an individual or individuals within our organization may be inappropriately sharing internal information with media representatives,” Bédard wrote in the message dated Nov. 9, 2016.

“With these concerns in mind, the senior leadership team retained an external expert organization to conduct a preliminary assessment around the circumstances of these breaches of our Code of Conduct.

“Their assessment has made plain to us that we need to take further steps to investigate this situation… I feel confident that all employees will cooperate as required during the pending investigation."

'Mistakes are being made at the NEB'

Presidia started its investigation after getting a sole-source contract. The NEB avoided a competitive process by keeping the price of the contract at $24,150, just below the $25,000 threshold. Any amount higher than that would have forced the government to stage an open competition for the contract. And so the deal went to Presidia, with whom the NEB had been working already.

The firm also received a $47,250 contract from the NEB last summer to provide “hearing security” for the initial federal panel sessions on the Energy East pipeline in different Canadian cities.

These were the sessions that would later go off the rails in Montreal on Aug. 29 with video footage appearing to show that private security agents initiated a violent altercation with a protester.

National Observer learned about Bédard’s warning to all staff after receiving a copy of his message. It was sent with an expression of despair from an unknown source or sources.

“Mistakes are being made at the NEB,” said the source or sources in a separate note accompanying the copy of Bédard's message. “Senior executives (are) spending their time and money trying to find out who’s leaking information. This is not very transparent... Staff are scared and unhappy.”

NEB spokesman Craig Loewen told National Observer on March 6 that the investigation of NEB staff by Presidia was still ongoing. He has declined to provide a status update since then. Like Bédard, Loewen defended the contract and stated that employees were "inappropriately sharing internal information."

"This activity poses a security risk and is a violation of our organizational and federal Codes of Conduct and Public Service Values," Loewen said in an email to National Observer. "In addition, the inappropriate sharing of information was damaging and hurtful to many NEB employees who come to work each day in service of Canadians and exemplify integrity and professionalism in their conduct."

The 'Values and Ethics Code for the Public Sector' outlines five values, the NEB wrote in the contract: respect for democracy, respect for people, integrity, stewardship and excellence.

When informed by National Observer about this investigation, the president of the union representing NEB employees said the case sounded like many others she has heard about in the public service.

"Whistleblowers are criminalized and I think Canadians would expect exactly the opposite: that they would be champions; that these people would be heroes to the Canadian public because they do put themselves at risk to blow the whistle," Debi Daviau, president of the Professional Institute of the Public Service of Canada told National Observer following the Earth Day March for Science rally on Parliament Hill in Ottawa.

The revelations about the NEB’s investigation into leaks has also coincided with renewed calls from public sector unions for the federal government to introduce legislation to extend governmental protection of whistleblowers who denounce misconduct by management.

"There’s a lot of work to be done on the legislation and in terms of the powers of the office of the integrity commissioner, if we’re going to ensure that people feel safe to blow the whistle," Daviau said. "As it stands now, it’s not safe. It’s 100 per cent unsafe and every single whistleblower has gone through 10 to 20 years of hardship as a result of standing up for what’s right for the Canadian people."

It's not uncommon for high-ranking executives to wish to silence whistleblowers. But efforts to punish people for denouncing misconduct are generally frowned upon in democratic countries like Canada.

Attempts to identify whistleblowers landed Montreal police in hot water recently after court documents revealed they were spying on journalists to get information. Those shocking revelations triggered a public inquiry in Quebec.

Presidia and NEB deny surveillance of journalists

After receiving confirmation that Bédard’s warning to the NEB staff was authentic, National Observer asked the NEB and Presidia repeatedly if their investigation included surveillance or monitoring of journalists. For more than a week, the NEB maintained that it didn’t approve of such tactics, without saying what the private investigators were doing. Throughout this period, Presidia, which has had numerous contracts with various federal organizations in recent years, also said it couldn’t comment on the contract or answer the simple question of whether the investigators were also spying on journalists.

It was only after National Observer journalists showed up in person on March 14 at Presidia’s Ottawa offices to ask questions that the NEB responded with a statement that the contractor “did not conduct any of those activities (surveillance of a journalist or journalists) on their own accord and we have confirmed that with them.”

When asked about that NEB statement, Presidia president Stephen Moore told National Observer in an email: “I can confirm that Presidia did not surveil you or any other journalist.”

Regardless of how the NEB describes Presidia's activities, the contractor's actions on behalf of the NEB may take place without public scrutiny.

While details of an internal federal investigation would be subject to full disclosure through Canada’s Access to Information Act, the NEB can use its contract with Presidia to get around this since the company isn’t bound by this law.

Canada's Access to Information Act is an accountability law that requires federal government organizations, such as the NEB, to release records within 30 days to anyone who pays a $5 fee. The legislation also allows government organizations to censor information, prior to release, if they have a valid reason for doing so. The person who now signs off on those decisions at the NEB is Bédard, the VP of transparency and strategic engagement.

Government organizations can request exemptions and censor some portions of records if they have a valid reason. But Presidia has no obligations to make its records available under the Access to Information Act, so anything it does is shielded from the legislation, as long as it is not sharing details, in writing, with the NEB.

This has already kept some of Presidia's work hidden: Bédard told staff that management was proceeding with a full investigation following an “assessment” done by the firm regarding the leaks. But when asked formally through freedom of information legislation for a copy of this advice from the firm, the NEB said it had none.

Bédard’s message to employees also stated that all staff have access to human resources personnel and staff training programs to resolve issues of concern or allegations of misconduct in the workplace, and that there was “ample evidence” that employees won't "hesitate to take advantage" of these options when they need them.

However, when asked to provide examples of this “ample" evidence, the NEB was unable to produce any proof that employees were able to denounce wrongdoing in the workplace and bring about change.

Instead, Bédard provided an alternative explanation for what he was talking about.

"I would like to point out that my use of the term 'ample evidence' was in respect to the fact employees of the NEB use the many resources in place to assist them," wrote Bédard in a letter responding to a formal National Observer request for access to information.

He said that employees could speak to supervisors, human resources specialists, an ombudsperson or an employee and family assistance program if they needed help.

He shared data showing how often NEB employees seek counseling from professionals at Homewood Health which runs the assistance program. There were 37 cases reported from April 1, 2016 until Dec. 1, 2016. This included nine cases of employees reporting depression, anxiety, self esteem or stress-related problems. Five cases in that period were reported to be related to workplace stress or a conflict in the workplace.

The NEB has about 450 full-time employees on staff.

Watson, Bédard and Touchette didn't respond to requests from National Observer for further comment.

Treated like a traitor, they turn your colleagues against you, says Sylvie Therrien

The whistleblower hunt by the NEB is familiar to Sylvie Therrien.

Therrien lost her federal government job in 2013 after denouncing a Conservative government crackdown to restrict access to employment insurance for Canadians in need.

According to Therrien, she was ostracized and bullied by management at the Human Resources Department after she went to the media with evidence that staff were being asked to target unemployed Canadians in search of work and to recover nearly $500,000 per year in federal employment insurance payments by demonstrating that the claims made were fraudulent.

Therrien said she hears the same story, over and over again, about people who expose wrongdoing in government.

“In a way, they are treating this individual or these individuals as traitors, like they (another federal department) did with me,” said Therrien, who reviewed a copy of Bédard’s message to all employees. “And they go to the point of turning your own colleagues against you, because the rest of the employees are afraid of losing their jobs, so they follow directions from senior management.”

It wasn’t fair for management to accuse whistleblowers of violating their employee code of conduct by going to the media instead of reporting wrongdoing to their supervisors, she added.

“We know that going internal doesn’t work,” Therrien said. “I’ve tried. This person or these people probably have tried and the people we’re supposed to go to internally are the people who are (approving) the deletion of emails and things like that.”

Whistleblowers inside and outside the NEB have helped to bring critical issues at the regulator into the public eye over the past year. These include:

Allegations that high-ranking officials ordered IT staff to delete evidence of what sources alleged were defamatory comments made by a senior NEB employee about one of its own employees in correspondence with a private investigator.

Allegations of excessive spending on public contracts, including evidence that the NEB spent about $1 million on new furniture for executives after spending millions to move its old furniture a few blocks across town in Calgary when the regulator relocated its head office.

Allegations about spending at new regional offices in Montreal and Vancouver. The revelations prompted questions which revealed the private meeting with Charest and the subsequent recusals from the review of the Energy East pipeline.

Cindy Blackstock, a member of the Gitxsan First Nation and long-time advocate for indigenous children’s rights, said the NEB simply went too far.

Blackstock, the executive director at the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada, was targeted by the Harper government after she denounced cuts to social services for indigenous youth. The NEB’s actions appear to her to violate Canada’s commitment to an international agreement that protects the right of people to criticize government organizations and defend human rights, the United Nations Declaration on Human Rights Defenders.

“At least in my situation, I was not an employee of the organization that was persecuting me,” Blackstock told National Observer. “For these employees, they are facing even more possibilities of direct harm to their career and to their families and to their personal livelihood than I would have experienced. So I think, particularly for federal government employees, that it’s vital that Canada observes the UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders.”

Blackstock encourages whistleblowers who are concerned about losing their jobs after denouncing wrongdoing to contact a support group such as Dublin-based Front Line Defenders.

The federal employees can then benefit from advice on how best to handle the situation, Blackstock said.

Comments

Bédard was new to the scene at the NEB. He had just been recruited over the summer, leaving a position at Quebec transportation company Bombardier. He accepted a newly-created position at the pipeline regulator as executive vice-president of transparency and strategic engagement. Only a few days into his new job as an executive at Canada’s energy regulator Sylvain Bédard asked for help.

Was it any wonder?

botched security arrangements at an NEB Energy East/Eastern Mainline hearing;

probing questions from the media left unanswered;

survey of the Canadian public shows NEB not trusted;

the NEB exposed in conflict of interest with industry (too cozy with the oil and gas industry and could not be trusted to protect public safety and the environment), and resultant precedent-setting Board Member recusals in the Energy East/Eastern Mainline hearing;

NEB eating their previous statements and forced to apologize for making false and misleading statements about a private meeting that its high-ranking officials had with a TransCanada consultant, former Quebec premier Jean Charest; (congratulations to Mike De Souza for his journalism award for this exposé);

preposterous amounts of money spent on moving and re-furnishing the new NEB Calgary offices, yet the National Observer noted, “the NEB said it had cut its spending on safety oversight such as inspections and the development of regulations by about $17 million in 2014-2015.”;

NEB management threatening violence against environmentalists, then wasting time and money to witch hunt and identify witnesses and the NEB staffperson who leaked the threat, veiling management's own misconduct, and resultant (not open to competition) ongoing investigation to defend against a "security risk", "possible breach and investigation.";

hidden records and redacted (entire contents) of an NEB internal memo of investigation (contract) released after info requested by media - what was the "validity" of this censorship?;

former whistleblowers saying, it appeared the regulator was trying to impose a code of silence… and intimidate staff to discourage them from questioning misconduct by management;

whistleblowers deemed a "security risk", and guilty of breaches of our Code of Conduct (but it's OK for management to threaten to taser people with opposing views? Is this the NEB's modernization of Canadian democracy?);

'Values and Ethics Code for the Public Sector' - breaching it appears good for the goose but not for the gander? Management's behaviour has hardly exemplified, respect for democracy, respect for people, integrity, stewardship and excellence.

Bédard’s message to employees also stated that all staff have access to human resources personnel and staff training programs to resolve issues of concern or allegations of misconduct in the workplace, and that there was “ample evidence” that employees won't "hesitate to take advantage" of these options when they need them. …

He said that employees could speak to supervisors, human resources specialists, an ombudsperson or an employee and family assistance program if they needed help.…

The NEB has about 450 full-time employees on staff.

… He shared data showing how often NEB employees seek counseling from professionals at Homewood Health which runs the assistance program. There were 37 cases reported (> 8% of staff just using internal assistance) from April 1, 2016 until Dec. 1, 2016. This included nine cases of employees reporting depression, anxiety, self esteem or stress-related problems. Five cases in that period were reported to be related to workplace stress or a conflict in the workplace.

Is it any wonder that NEB staff are seeking assistance??? Wouldn't any employee need and seek support internally and externally, when working under the following conditions? :

Whistleblower hunt - Treated like a traitor, they turn your colleagues against you, because the rest of the employees are afraid of losing their jobs, so they follow directions from senior management.”... ostracized and bullied by management...This is not very transparent... Staff are scared and unhappy.”;

MORALE SO BAD THE NEB STOPPED ASKING March 28, 2016 National Observer- reported on the NEB's internal surveys of its 500 employees released under access to information requests, revealing collapsing morale and questionable NEB management choices; “Internal survey results show bad morale in the workplace and mounting frustrations with management,” …“NEB employees are losing faith in their bosses, and are increasingly frustrated and puzzled by decisions they are instructed to implement.” Barely one-third of employees surveyed agreed that they understood the “reasons for management decisions.”;

The National Observer reported, "The NEB began surveying its employees in 2011. “But the alarming results gathered in 2015 prompted management to cancel the quarterly surveys just as the federal election campaign was getting under way in Canada,”

What percentage of NEB staff don't answer the survey?

Does this behaviour by the NEB represent a Canada anyone wants to or should work under and live in?

The federal government MUST introduce legislation to extend governmental protection of whistleblowers who denounce misconduct by management, colleagues so they are safe to disclose, rather than being denounced, as the NEB is doing. In the absence of such protection, we need the National Observer as our champion, a journalistic hero to the Canadian public.

"Modernized" NEB Ethics Code: Do as I say, not as I do. Or else…

Hey. I sent a screenshot. Did you get it?