Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

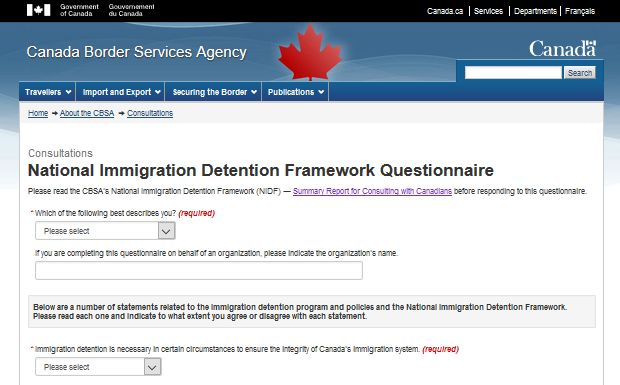

Consultation is good… until it isn’t. At least, that’s a conclusion one could reach on an online survey recently published on a federal government website about Canada’s immigration detention system.

The government can and should be consulting Canadians about a whole host of issues. But one thing is certain – human rights should not be up for negotiation in the court of public opinion.

Canada has, unequivocally, violated international law on immigration detention. The UN Human Rights Committee has pointed out practices contrary to Canada's human rights obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights in its last report and advocacy groups have pointed this out in other instances. In the past few years, several significant human rights abuses relating to immigration detention have come to light.

More than 60 immigration detainees held a hunger strike last year to protest indefinite detentions in maximum security prisons and prison conditions that include lockdowns and solitary confinement. At least 13 people are known to have died since 2000 while in immigration detention. A University of Toronto study found that migrants with mental health issues were routinely detained in maximum-security jails — sometimes for years.

In February, researchers revealed further findings that the rights of dozens of children being held in immigration detention centres were violated. Last year, the University of Toronto found that a 16-year-old Syrian refugee, sent to Canada by parents hoping that he would find safety here, was left in solitary confinement for three weeks and ordered deported, even though he had committed no crime and posed no danger.

And last month, the Toronto Star reported that Canada Border Services Agency officers, responsible for sending some immigrant detainees to maximum-security provincial jails, receive no training and, by their own estimation, note that their assessments should “not be construed as an accurate representation of the subject’s risk or mental health status.” Exactly like convicted inmates, these immigrants must wear orange jump suits, submit themselves to strip searches and remain in their cells 18 to 24 hours a day.

International law is clear

Regardless, the government still wants to hedge its bets by evaluating public support for such (slightly leading) statements as: “Immigration detention is necessary in certain circumstances to ensure the integrity of Canada's immigration system” and “Immigration detention is necessary in certain circumstances to ensure public safety and security.” Should children should be held in detention? Should there be a limit on how long a person could be detained? Gee, it’s as if a United Nations body hasn’t just strongly urged us to get our act together on these very issues.

Rules on immigration detention are already clear in international law, including the 1951 Refugee Convention. International law holds that detention must be lawful and justified (meaning that detention cannot be indefinite). Moreover, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) discourages the routine detention of asylum seekers, even those who arrive irregularly.

Meanwhile, the Convention on the Rights of the Child implies that the best interests of the child must be paramount in addressing their asylum claims, and the New York Declaration adopted by the UN General Assembly last September urges countries to “end the practice of detaining children for the purposes of determining their migration status.”

The disconnect between conditions of immigration detention in Canada and international norms can be measured against the bigger picture of Canada’s respect for humanitarianism and human rights. When Prime Minister Justin Trudeau attended the Women in the World Summit in New York last week, he was asked how it feels to be the “new big liberal superhero.” Beneath the fanfare, however, Canada’s support for international multilateralism has wavered.

The Trudeau government refused to close a loophole in Canada’s law to ratify the United Nations treaty banning cluster bombs; a controversial clause in the bill allows Canada to use cluster munitions in joint missions with the United States. Ditto for Canada’s arms sales to Saudi Arabia. “If Canada leads, the world will follow,” Malala Yousafzai said in her address to Parliament last Wednesday. This record of half-measures and equivocating surely doesn’t stand up to the aspirations she has set out for us.

So far, the government’s new framework on immigration detention moves in a promising direction – but sets out a general, non-committal set of intentions rather than a solid plan. The government is likely concerned about potential unpopularity of aligning Canada’s practices on immigration detention with international norms. After all, candidates in the Conservative leadership contest are in a race to the bottom to take the most hard-line position on the issue of asylum-seekers crossing the U.S.-Canada border. And a new Angus Reid poll shows that most Canadians prefer tighter border controls over assistance for asylum seekers.

Any federal policies on Canada’s immigration and refugee system rolled out in coming years are likely to become a wedge issue in the 2019 election campaign. And if the government were to use the results of a public survey to abscond on serious human rights obligations – that would be cowardice.

Comments