Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

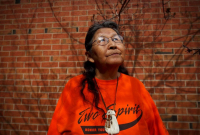

For 16 years, Maggy Gisle thought her lot in life was to be a "junkie, a prostitute and a drug dealer."

Now, Gisle — once known as "Crazy Jackie," a fixture on the Downtown Eastside who would inject cocaine to suppress her nightmares of childhood sexual abuse — has returned to her old Vancouver haunts, this time with a nobler mission.

Gisle spends her own time and money collecting stories and information from others on the notorious strip, hoping to provide the material to the forthcoming national public inquiry into missing and murdered indigenous women.

She counts herself among the growing ranks of aboriginal Canadians, advocates and family members who are growing frustrated and despondent about a lack of a clear timeline on when they're going to be able to share their testimony.

While the commission is set to hold its first public hearing on May 29 in Whitehorse, other community meetings won't take place until later this fall at the earliest.

No other dates have been confirmed for additional hearings, an inquiry spokesperson said in a statement, and the commission has yet to develop a database comprising the names of the victims.

Ensuring voices don't fall through cracks

"There are now about 294 families who have reached out to the national inquiry and identified as wishing to participate," said communications director Bernee Bolton.

"There is an extensive community engagement and communications plan to connect to families and survivors."

Gisle has spent about $1,300 of her own savings to travel to Vancouver from her home in Lund, B.C. — a meandering, five-hour trip by car — to ensure the voices of women like her, many still living on the streets, do not fall through the cracks.

"The inquiry is all very well and good, but the public won't get a full picture if they don't know what is actually going on on the streets right now," said Gisle, who plans to gather material by videotaping interviews with the women.

"All this time, they could have been compiling information and getting statements or at least doing an updated list for the missing women and everything is on hold ... the public is frustrated, too."

Timelines needed

Susan Vella, the inquiry's lead legal counsel, said it will be critical to build relationships in order to gain the trust of survivors.

One way to do so, she said, would be to ask individuals or organizations to reach out to their networks of friends, family and acquaintances in order to encourage them to take part — precisely what Gisle is trying to do.

"It is to build on a pre-existing relationship of trust and respect and facilitate a connection with us directly — having an intermediary, if you will," Vella said in a recent interview.

But earning trust — and keeping it — will be increasingly difficult without clear timelines, experts say.

Dave Dickson, a former police constable who spent 28 years working on the Downtown Eastside and forging trust with women like Gisle, said he isn't particularly optimistic about the work of the inquiry or the recommendations that will flow from it.

The federal government has earmarked $53.8 million for the two-year national public inquiry; the commission must produce an interim report by November.

The root causes of violence against indigenous women are already well-known, said Dickson, describing deep-seated issues like endemic sexual abuse in communities as an unspoken taboo.

Undercurrent of abuse

"I'll write them a letter and tell them what the issues are — why the women ended up on the farm (of serial killer Robert Pickton)," Dickson said in an interview.

"There's a huge problem with people running away from (abuse on) the reserves and they come down here, down to the Downtown Eastside, and they get hooked."

Gisle, who watched friends disappear during the Pickton years, said there's an unacknowledged undercurrent of abuse, linked to the residential school system, that is often tolerated in indigenous communities.

She said her own experience of being sexually abused as a child by a birth father who himself was in residential school is why she became an addict, a story shared by countless others who struggle with similar demons.

"I have never, ever met anybody (on the Downtown Eastside) that had not been abused ... from varying degrees, from incest, rape, being abused by their brother, being abused by an uncle," she said.

Gisle once wanted to die on the streets of Vancouver. Today, she wants Canadians to know that the people there now are in desperate need of a way out.

"Underneath the dirt, the grime, the addiction and the prostitution, there is a human being that is suffering," Gisle said.

"We don't know their story ... I don't want to die today; I want to live ... I don't think my good life is only for me."

Comments