Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Canada’s environment and health ministers leap into action, wielding giant pens the size of their bodies.

“We need stronger laws to protect Canadians,” declares Environment Minister Catherine McKenna, after hearing from a concerned mom.

“We’ve got this!” adds Health Minister Jane Philpott.

No, this isn’t a Liberal Party television commercial.

It’s a bit of comic book fiction, promoted at an Ottawa reception on Monday night by a coalition of five environmental groups.

Environmental Defence, Ecojustice, Équiterre, the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment and Tides Canada released the comic to highlight the “historic opportunity” facing Canadians on ridding the country of what they consider to be dangerous toxins in consumer products.

The government currently allows small concentrations in health products, cosmetics, drugs and toys of three substances that the environmental groups say McKenna and Philpott have the power to ban.

After the fictional ministers ban the substances, the comic's narrator states: "not all heroes wear capes!"

National Observer asked both ministers about their reaction to the use of their images to promote this cause, and whether they agreed the substances should be banned.

Neither answered either question directly. McKenna's spokeswoman Marie-Pascale Des Rosiers said in a statement that the government takes the health and safety of Canadians and the environment "very seriously."

Philpott's spokesman Andrew MacKendrick said: "our government is committed to protecting the health and safety of Canadians, and to evidence-based decision making to ensure we uphold this commitment."

Getting the Tories on board

The House of Commons environment committee has been reviewing Canada's legislation governing toxic substances, the Canadian Environmental Protection Act (CEPA), since March 2016 and is expected to issue recommendations on changes before MPs rise for the summer.

The environmental groups say that law is outdated and are pushing the government to strengthen its public health provisions. They want a review of substances to be mandatory when new science or data emerge or when bans occur in foreign jurisdictions, for example.

They also want the government to ban substances "of very high concern" from use "unless they can be proven safe for the proposed use," and require mandatory labelling of consumer products with substances "suspected of causing adverse health effects."

The law is "one of the most important pieces of legislation in this country,” said Bruce Lourie, president of the Ivey Foundation, in comments to the crowd gathered at Ottawa’s Sir John A MacDonald building.

Will Amos, Liberal member of Parliament for the Ottawa-area riding of Pontiac and a member of the environment committee, told the crowd that the committee was in the “thick” of negotiating different elements.

He said coming to an agreement with opposition members on the committee on recommendations would lead to more resilient rules in government.

"It's a lot harder for a department to ignore recommendations the Conservatives actually agree to,” said Amos.

Marginalized communities bear 'toxic burden'

Wendy Cooper, program lead for Ontario and national watersheds at TIDES Canada, said the current review of CEPA and another upcoming review of the Pest Control Products Act provide a “historic opportunity” to rid Canada of toxins, despite it being "certainly under the radar for a lot of environmental groups."

The group also showed a short video with testimonials by such analysts as Dayna Nadine Scott, a professor at Osgoode Hall Law School and editor of a book on gender and toxic substances.

"Some privileged communities and consumers can shop their way out" of a toxin-filled life, said Scott in the video, but "marginalized communities" and others are "left to bear the toxic burden."

Three substances in the crosshairs

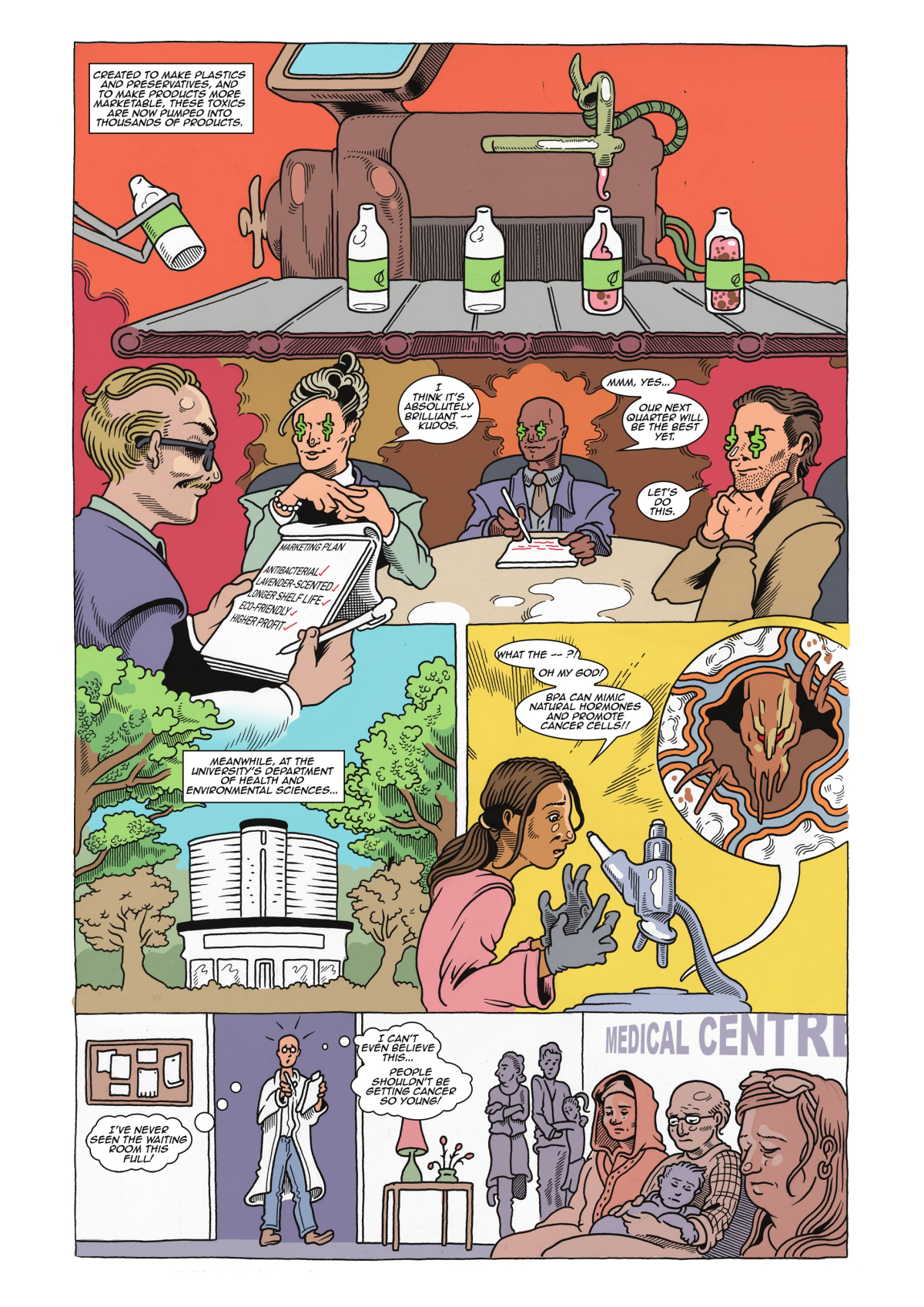

The group’s comic book, called “Uncanny Toxics: Vanquishing an Invisible Enemy,” highlights three substances: Bisphenol A, triclosan and phthalates.

Bisphenol A, also known as BPA, is a substance used to make plastics that was banned from baby bottles, while triclosan, which can be found in toothpaste and soap, poses a risk to plants and fish, according to the federal government.

Phthalates, a group of chemicals, may pose a risk to reproductive and developmental health, the government says.

Canada already acknowledges that triclosan “poses a risk to the environment,” that newborns and infants are “most vulnerable” to BPA, and that some phthalate substances “may have common health effects of concern.”

More legal changes could be coming

The review of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act is one of several environmentally-focused reviews that the federal Liberal government has committed to carrying out.

This month, a Trudeau government-appointed panel of experts recommended the replacement of the national pipeline regulator with a new federal agency. In April, another federal expert panel proposed an overhaul of how environmental assessments are conducted in Canada.

In March, the Commons transport committee also tabled recommendations on the Navigation Protection Act, and in February the Commons fisheries committee released a Fisheries Act review report.

Jonathan Wilkinson, parliamentary secretary to the environment minister and an associate member of the environment committee, also called the implementation of Canada’s Species at Risk Act a "big issue."

The act, which aims to protect endangered species from going extinct, has been targeted by environmental groups who say the government hasn't followed through on requirements to assess threatened woodland caribou every six months.

Editor's note: This story has been updated at 7:10 p.m. ET to include a new comment from Philpott's office.

Comments