Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

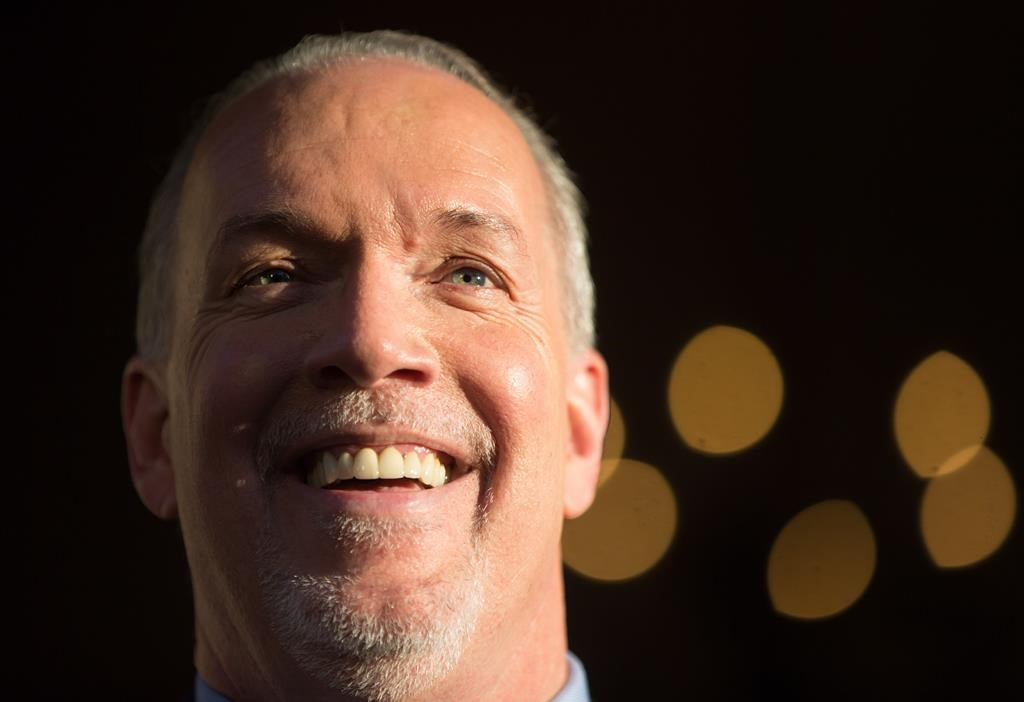

John Horgan's fight for society's underdogs started early in life.

His father died from a brain aneurysm when he was 18 months old. Money was tight for his mother who struggled to raise four children alone and there were times food hampers were delivered to the Horgan home.

British Columbia's next premier said in an interview earlier this year those personal struggles opened his heart.

"My mom taught me if there was someone who needed help you should step in and help them,'' said Horgan, 57, who grew up wanting to be a social worker. "I was raised to be kind to people.''

Those principles emerged in the election campaign as Horgan promised $10-a-day child care, as well as more spending on health care and education.

On Thursday, he got the chance to turn those promises into government policy as he became the province's premier-designate after the Liberals were defeated in a non-confidence vote.

"I look forward to working harder than I've ever worked before to make sure that this great province continues to grow and that the prosperity that we all want to see for ourselves, we can make sure that we share that prosperity with others," he said in Victoria after meeting with the lieutenant-governor to accept the responsibility of governing.

Horgan said he tried to reach his wife Ellie with the news, but had to leave a voicemail because she was outside.

"I said, 'It's the premier calling, I will get back to you,' so I've made the most important call I had to make."

Horgan wasn't always on the path to becoming a political leader. As a teenager, he skipped school and played the role of troublemaker.

But when a high school basketball coach took him by the collar and told him to report to the gym, Horgan turned things around and devoted himself to sports and academics.

Horgan, who fought bladder cancer a decade ago, has said he has no memories of his father.

"My brothers, my mom and my sister would always tell me the stories," he said in an interview before the campaign began. "My brothers would tell me stories about how he was a basketball fanatic."

At 6-2 tall, 250 pounds, playing team sports taught Horgan he could make points without resorting to goon tactics. He worked on staying out of the penalty box and scoring points instead.

Those tactics haven't stopped his imposing presence and verbal skills from coming across as angry or confrontational, as it did on the campaign trail.

The first leaders debate was largely remembered for a testy exchange between Horgan and Liberal Leader Christy Clark after she touched his arm and told him to calm down.

In the second televised debate, the moderator also singled out Horgan, asking him if he had an anger-management problem.

Horgan said he gets angry when he sees government inaction on a range of issues from underfunding of schools to a lack of support for children in care, which has resulted in suicides.

"I'm passionate. I got involved in public life because I wanted to make life better for people,'' he said at the debate.

Horgan met his wife while they were students at Trent University in Peterborough, Ont. They have two grown sons, Nate and Evan.

Horgan was acclaimed NDP leader in 2014 after the party's demoralizing 2013 election defeat, a campaign they were widely expected to win but it ended with Clark leading a remarkable comeback for the Liberals.

Comments