Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Leaders of the world's largest economies are expected to drag U.S. President Donald Trump into making some sort of a statement on climate change this weekend, but environmental groups say the negotiations are going down to the wire.

The 2017 G20 summit in Hamburg, Germany is the first major gathering of world leaders since Trump announced that the United States would pull out of the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change. Trump and members of his cabinet have expressed doubts about scientific evidence linking human activity to climate change, but have never provided proof for their own claims.

They have also announced plans to slash funding for environmental monitoring and enforcement, while loosening federal rules that were designed to crack down on harmful pollution from oil, gas and coal companies.

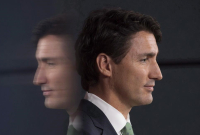

German Chancellor Angela Merkel has made it clear that fighting climate change will be firmly on the agenda. It’s an issue that has sucked in Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, who said after Trump’s rejection of Paris that he was “deeply disappointed” and has reached out to other allies on climate action.

Trudeau later admitted that he “impressed upon” Merkel the importance of standing “together” with the U.S. despite its rejection of the Paris accord.

“I think we can expect that something will be said on climate, and we can also expect [negotiations] to potentially go into the last night,” said Lutz Weischer, team leader for international climate policy at the non-profit Germanwatch, based in Bonn, Germany. “It’s going to be tricky and controversial.”

Weischer, who was speaking at a July 5 briefing organized by the international environmental group Climate Action Network, said Merkel has “made it clear that she sees the need to have strong signals on climate come out of this summit.”

But she also has two other objectives, he said: to have as unified a G20 as possible, and to also recognize differences between nations on some points. That means “she has to find the balance between these objectives,” he said.

The key advisors to each G20 government, tasked with laying the groundwork for the summit, met Tuesday and Wednesday in Hamburg, said Alden Meyer, director of strategy and policy with the Massachusetts-based Union of Concerned Scientists.

Meyer said the advisors went until midnight Tuesday hammering out trade issues, and were expected to tackle climate issues late into the night Wednesday.

“We expect there to be some elements of the communiqué which are a consensus among all the countries, including the U.S,” he said.

It’s not clear yet which countries Merkel will be able to get on board with a statement supporting the Paris treaty, environmental groups have said.

McKenna wants a "clear message"

All members of the G20 have signed the treaty, but how strongly five countries in the group—Russia, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia and the U.S.—will support a statement upholding the Paris treaty, this weekend, is up in the air, The New York Times reported Wednesday.

“It would be great to have a clear message that everyone understands we need to be taking action on climate change, and the Paris agreement is critical to that. Canada is really pushing for that,” the newspaper quotes Environment Minister Catherine McKenna as stating.

Catherine Abreu, executive director of Climate Action Network Canada, said it was impossible to see the G20 happening in isolation from the friction caused by world events, such as Trump's decision to pull out of the Paris treaty.

“Indeed, it must be connected to a variety of other events and efforts taking place in the lead-up to the G20 and in the coming year,” she said.

Supporting Paris in deeds, not just words

G20 states collectively emit over 80 per cent of the world’s carbon dioxide, which means they are crucial to achieving the Paris treaty’s goal of keeping the global warming below two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels this century.

Countries should not only be supporting the Paris treaty, but adopting stricter rules around limiting their carbon pollution, environmental groups have stressed.

“What’s really on the agenda this Friday and Saturday is moving forward with implementation of Paris and decarbonization of the global economy,” said Meyer. “We need action to strengthen the commitments that countries put on the table in Paris, because as we all know, they are not sufficient to achieve the temperature limitation goals that countries agreed to in Paris.”

That includes Canada: despite the Trudeau government's environmental efforts, such as proposing reforms to Harper-era environmental laws and claiming the "right" to price pollution and tax fossil fuels, Canada's 2017 national inventory report on greenhouse gas emissions shows the country will miss its 2030 target without new measures.

“It’s important for us to use this moment to pivot from understanding that the Paris agreement, and various countries’ commitments to that agreement, are strong, towards implementation of that agreement,” said Abreu.

That might be furthered by the work of an international joint group on climate and energy, which has “produced something of a draft action plan that’s basically a to-do list of different things that countries need to do to implement the Paris agreement,” said Weischer.

“It’s not just reaffirming the Paris agreement and saying the issue is important, it’s going much more into the details of what you will do,” he said.

Such an action plan would “hopefully be agreed to by everyone but the United States,” said Meyer. “This will really be a new element in the G20 process, if we can pull this off with all but the United States on board.”

G20 climate initiatives in question

Also unclear is whether the G20 as a whole will endorse a number of other climate-related initiatives at the international summit.

For one, there are the final recommendations of how the financial sector can account for climate-related issues — a report that was commissioned by G20 finance ministers and central bank governors in April 2015 and released June 29.

Then there is the Green Climate Fund, a pool of money within the UN climate change framework that is supposed to help low-income countries mitigate and adapt to climate change, and that was reaffirmed by G20 members last September. The fund has been targeted by Trump, who called it the “so-called Green Climate Fund,” saying it costs the U.S. an unfair and "vast fortune."

The G20 also reaffirmed its commitment last year to “rationalize and phase-out inefficient fossil fuel subsidies,” a commitment that it originally made in 2009.

“We hope that many of these elements will be enforced by leaders in Hamburg,” said Weischer.

Editor's note: Alden Meyer has no relation to the author.

Comments