Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

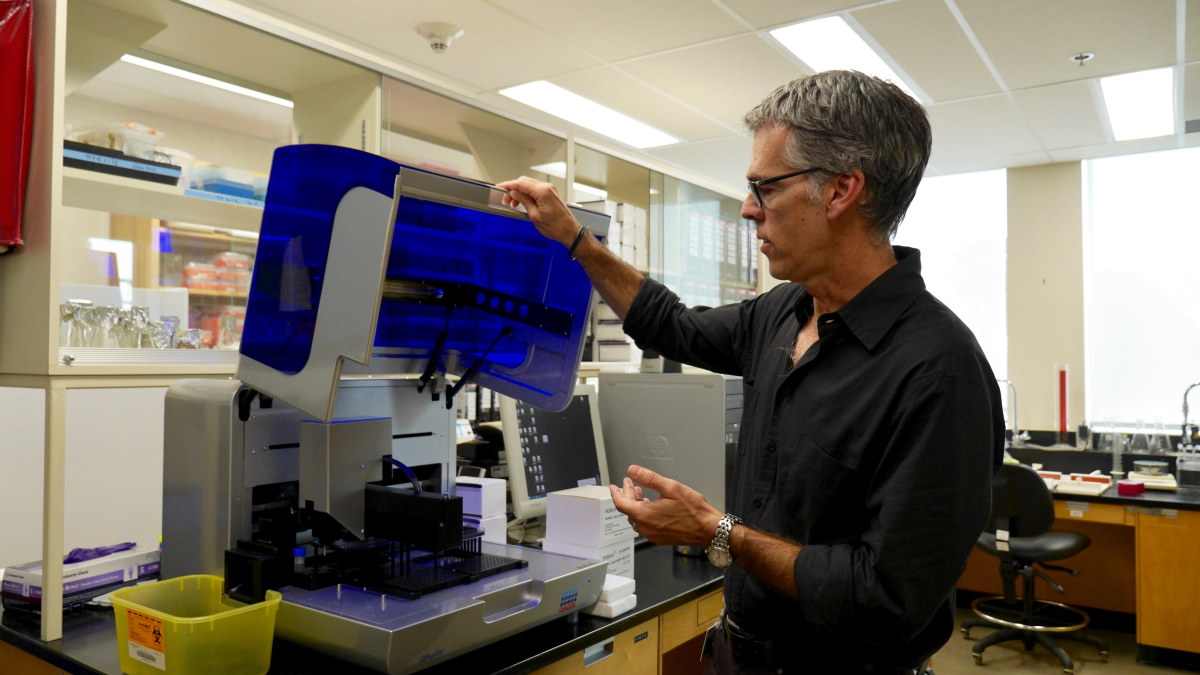

Thousands of small test tubes were set up in neatly organized rows in the cupboards of Armand Séguin’s laboratory.

Soon, the scientist would be filling them up with sap squeezed from the bark of ash trees.

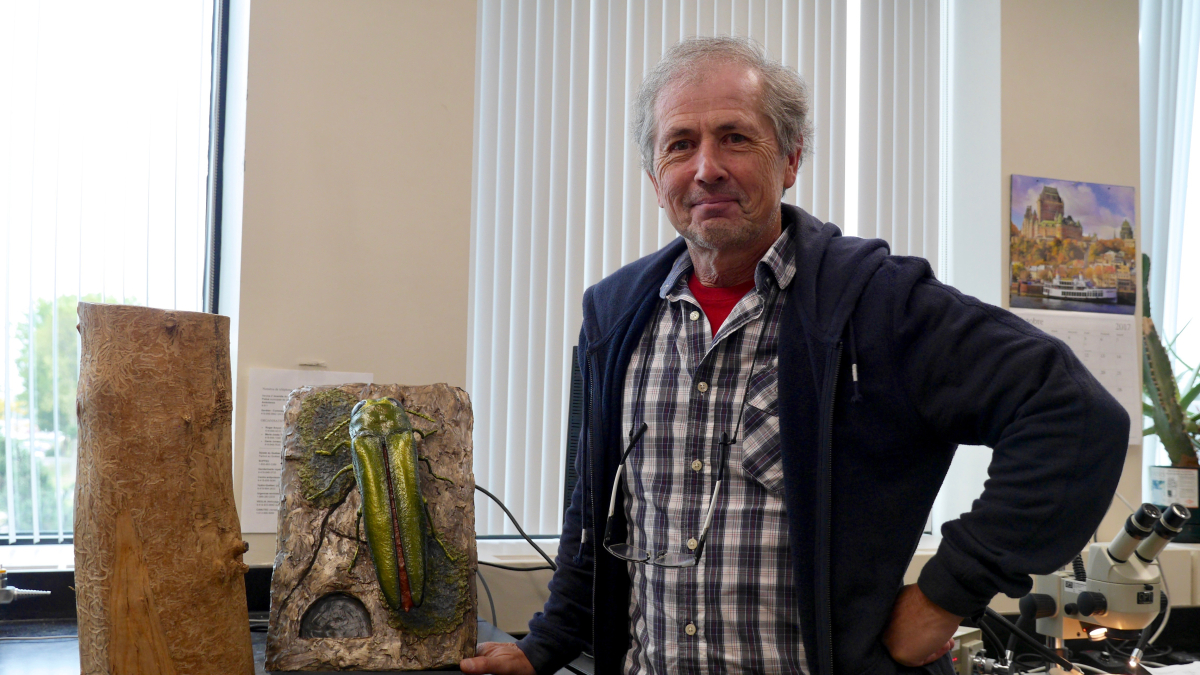

Séguin has been studying cancer for more than two decades. Now he's turned his expertise to stopping the spread of the destructive emerald ash borer, a green metallic-looking beetle that is smaller than a fingernail.

Down the hall at the Laurentian Forestry Centre, scientists Yan Boulanger and Sylvie Gauthier are studying the ecological impacts and the public safety implications of wildfires. Their work is important to prepare for the impact of climate change that could accelerate the risks and intensity of wildfires.

The centre in Quebec City is one of five federal research hubs in Natural Resources Canada's Canadian Forest Service.

In peak summer seasons, some 200 employees are on the job at the centre, with staff of about 120 the rest of the year. Their research findings are used to assist the private sector and guide policies in numerous federal departments, such as Public Safety Canada, Health Canada and Indigenous Affairs Canada.

General director Jacinthe Leclerc said the centre's mission is to transfer the knowledge developed within its walls to other scientists and industry through data bases, conferences and publications.

Scientist explores tweaking tree DNA

Séguin's target may look harmless at first glance, but once it settles in an area, the emerald ash borer can wipe out about 30 per cent of the surrounding trees in each subsequent year. The exotic insect from Asia spread to North America 15 years ago.

The insect munches its meals beneath the bark of the trees, out of sight. So the trees generally don't show signs of infestation until they start losing their leaves and it's too late to save them.

Local communities commonly use an insecticide called Triazin to drive the green invader away. But because it's expensive, scientists say that cities often use it sparingly to save only a few trees at a time.

Séguin is exploring a test that could provide detection of the invisible emerald ash borer well before it damages the tree. The process begins with a "blood test" of a small piece of bark from a vulnerable tree to detect infection.

“We look at the genetic profile (of the tree) a little bit like (what we would do) with someone with diabetes," said Séguin. "There are markers in the person’s sugar level or insulin rate for instance. We can’t measure insulin on a tree but through molecular methods, we can measure its stress level so we are trying to see which genes are (consistent with) the stress caused by the emerald ash borer.”

Federal hub also eyeing increasing forest fires

The emerald ash borer, however, is not the only threat to the forests on the scientists' radar. Noting fires in Fort McMurray last year and in British Columbia this year, Gauthier predicts more fires burning bigger areas in the future.

“We know that with climate change, risks are going to rise but we are going to try to see exactly to what extent they will rise and where they will do so,” added Boulanger.

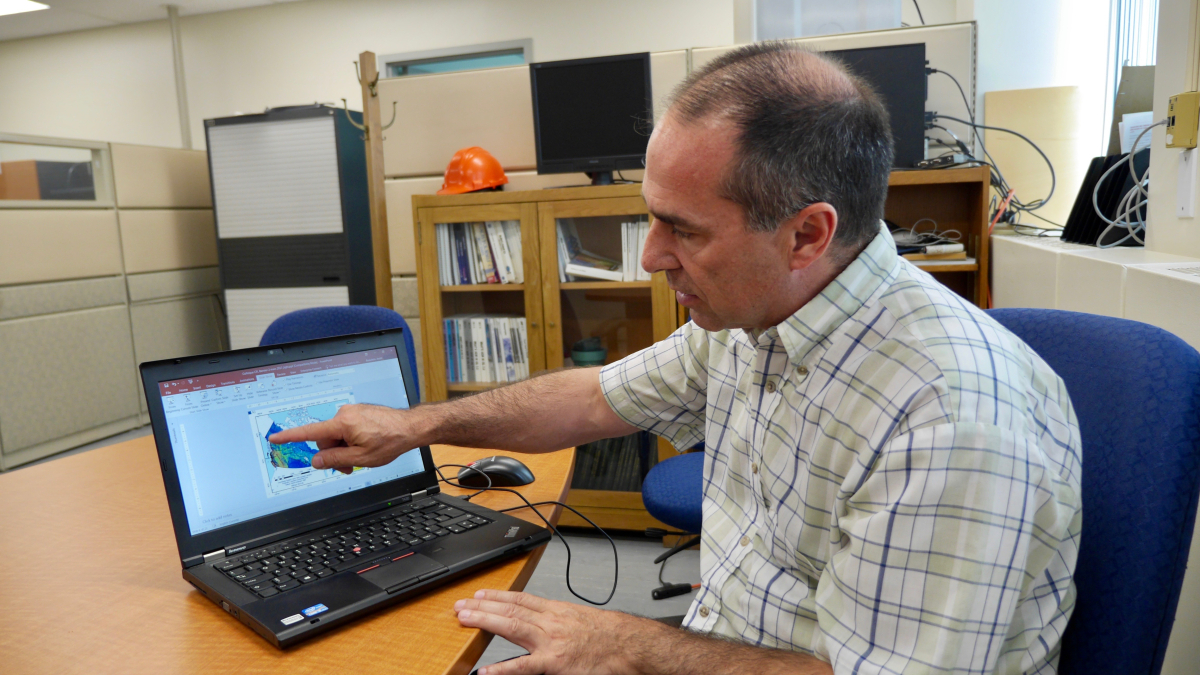

Gauthier and Boulanger study forest fire risk levels with the help of maps created by colleagues that show the composition and age of the tree population. Younger forests with leafy trees are less likely to go up in flames, while the older forests are more vulnerable.

"It's almost as if the fire is a hunter or a predator," said Gauthier. "It chooses certain areas such as older forests and the ecosystems that are made up of coniferous trees are burned more often... or more likely to be the ones that were burned in fires over the past 10 years."

The Canadian Forest Service received an additional $1 million per year in federal funding to examine climate change impacts. Gauthier and Boulanger have developed projections by combining meteorological and climate models with their previous mapping of forest fires.

In their models, they also take into account communities, infrastructure and industries.

Boulanger said Indigenous communities were unfortunately among the most vulnerable to the risk of forest fires in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta as well as in the northwest parts of Quebec. Overall, he projects close to four million people in Canada will soon be in regions at risk of fires with higher frequency.

Other scientists at the centre create tools for research.

Huge amount of data available

André Beaudoin and Luc Guindon are scientists in charge of gathering satellite data and turning it into usable maps. In the past, spatial scientists like them would take aerial photos and interpret them, Beaudoin said.

“(They would say) ‘this is a population of (jack) pines of that height and that intensity’ and then they would take samples on the ground in these populations to estimate the volume of biomass,” he said.

Nowadays, he and colleague Guindon receive billions of pixels captured by several satellites owned by American, Canadian and European space agencies that amount to a total of 30 terabytes. If you consider that an average movie takes up about 2 gigabytes, it would mean that Beaudoin and Guindon are using the equivalent of nearly 15,000 movies worth of data to map Canada’s forests.

As the quality of images captured by satellites grows, Beaudoin said the challenge is to keep pace with computer capacity to process and stock images.

“We find ourselves with a phenomenal quantity of data — it’s part of the big data era in which we get a massive amount of possible data," he explained. "We need to select the best possible data for the information that users are looking for."

Users like Gauthier and Boulanger for instance, want to know the composition of the Canadian forests, so they have to find a statistical model to make the pixels reveal the information that they’re looking for.

Every year, Beaudoin tracks the changes of the national forest biomass. This has important implications for policies and analysis for climate change.

“Biomass is a key variable for applications such as climate interactions, or the atmosphere in the context of climate change or to know the quantity of available biomass for bio energy,” Beaudoin said.

With issues such as the emerald ash borer, he also co-operates with both the American and Mexican Forest Services since the insect is a transnational problem.

When the pest was detected in Quebec City in the summer of 2017, Robert Lavallée, a scientist and an emerald ash borer specialist at the centre, quickly rushed with coworkers to set a trap on a “suspicious” tree as part of their investigation.

“From the ground, we couldn’t see if there was emerald ash borer, we can’t even see it with binoculars,” Lavallée said. “We set up traps on the Friday and the next Monday, we harvested it.”

The scientist had captured 50 insects, an “enormous” amount for this species that Lavallée calls “our worst nightmare.”

Lavallée had already been working on a solution to fight the pest in cities like Montreal, and in Ontario forests like those close to Sarnia. A specific Canadian fungus had caught his attention — it could get inside the pest and kill it.

His plan was to set a trap for emerald ash borers with pheromones, the odour of females, and kairomones — the odour of freshly cut grass. The special fungus would be placed inside the trap and as soon as the beetle came in contact, it would become infected and die within the next five days. Before dying, it would have enough time to spread the deadly fungus to its peers.

Lavallée hopes this introduction of a natural regulator could be successful where an infestation is still under control. His studies have shown 80 per cent of emerald ash borers infected with the fungus died.

“We demonstrated that our results were conclusive and we’re at a stage where we’re going on a bigger scale," he said.

His fungus is in the approval process at the Pest Management Regulatory Agency, the Health Canada office responsible for pesticide regulation. Lavallée has seen it in use already in the U.S. and in China where the fungus dropped in ‘bombs’ into forests to fight other pests.

Scientists at the centre are themselves attracting attention with their expertise and projects.

For example, a special facility at the centre opened at the end of 2016 allows scientists to study forestry insects in an environment that can reproduce natural conditions for long periods of time. The facility is composed of a loading area where logs are prepared and stored in a depot with 600 cages — plastic buckets — in a controlled humidity environment, and a laboratory to analyze and identify insects.

It's a rare infrastructure, the only one in Canada, said Jean-Michel Béland, the biologist in charge of the depot.

“German scientists came, they want to develop a log depot like this one, but an outdoors one.”

Help for maple trees possible too

The Canadian scientists also rely on research from abroad to guide their work.

Séguin, the genomics scientist trying to solve the emerald ash borer problem through DNA, explained he was only able to advance his research because European and American researchers had managed to fully understand and identify the ash tree’s genome. Genomes are the genetic material of an organism made of DNA.

While the genomes of trees can sometimes be large and complex, Séguin said the ash tree had a smaller genome that would be easier to analyze in order to develop a “dictionary of the genes” for the species.

Once he has that completed, Séguin said he would be able to detect the emerald ash borer in trees in time to save them. But he also said he wanted to go further and find ways to genetically improve the tree so that it can be resistant to the insect.

“Now, it’s become a tree that lost its nobility in urban forestry because people think that they’re not going to plant ash trees with the emerald ash borer infestation,” he said.

He added that this research could also be applied on maple trees which are being struck by the Asian longhorned beetle, another pest.

“If we develop an expertise with the duo ash and emerald ash borer, we’ll have particular knowledge, we’ll be able to apply them faster on maple trees for example through the same approach,” he said.

Note: This article was updated at 2:05 a.m. ET on Friday, Dec. 1, with corrections.

Comments

Exciting news; thanks for this.