Nuxalk people roll up their sleeves to construct a solution

Story and images by Emilee Gilpin

Bella Coola Valley is tucked between fjords that drop into the ocean and massive snow-peaked mountains. Nuxalk language and oral history teacher Clyde Tallio will tell anyone with an open and good heart, about how the mountains were the landing place of the first ancestors.

Their smayusta (history), Tallio says, remind the Nuxalkmc (Nuxalk people) of how the mountains were originally formed and how their first ancestors were gifted the land by the Creator, guided by the descending eyelash of the sun.

Bella Coola lays 100 kilometres east of the Pacific coast in the heart of what most Canadians call the Great Bear Rainforest, the largest temperate rainforest left in the world. For locals returning from medical appointments or visitors drawn to the ski hills and cottage-styled lodges, there is a direct flight from Vancouver to the humble Bella Coola airport. But depending on weather, the plane often stops at Anahim Lake to transfer passengers by bus down “the hill,” which is really a mountain.

Everyone knows everyone in Bella Coola. Clarence Hall, 92, came to Nuxalk territories as a young man, after the Second World War, working years as a logger. He is known for approaching a table of strangers in one of the two restaurants in town, retelling the time he was taken into a concentration camp during the war, or the time he was attacked by a cougar. He shows teeth marks in his worn hat. They’re all true stories, locals will confirm.

A group of men meet in a tiny diner on the main street in town everyday, sipping coffee and sharing gruff stories and stares. And when news of a missing dog gets out, word spreads like mismanaged B.C. wildfires. Nuxalk and non-Nuxalk alike will all be on the lookout. Between 900 and 1,000 non-Indigenous residents of Bella Coola mingle with the Nuxalk community of equal population, but it wasn’t always so.

Like other First Nations, the Nuxalkmc were targeted by colonialism. The Nuxalkmc survived the intentional spread of smallpox in 1862, which decimated populations. They survived the ban of their potlatch governing system from 1884 to 1951, and the genocidal violence of residential schools.

Eventually, the Nuxalkmc moved away from their traditional bighouse system and over time, like many First Nations reservations, the communities were obliged to live in housing conditions, imposed by government, using standards, contractors and consultants unfamiliar with West Coast weather and the community’s social, cultural and economic needs.

The resulting shabby housing was in desperate need of renovations. Like many underserved reservations across the country, the community lived with a housing crisis for generations.

Led by its chief and council, the Nation started an apprenticeship program in 2015, using their talent and territorial knowledge to reinstate pride and respect. Through the community-based program, which matches Nuxalk apprentices with advanced skilled workers, members of the Nuxalk Nation are building their own homes with their own resources, just as their ancestors once did.

Third world conditions in a first world country

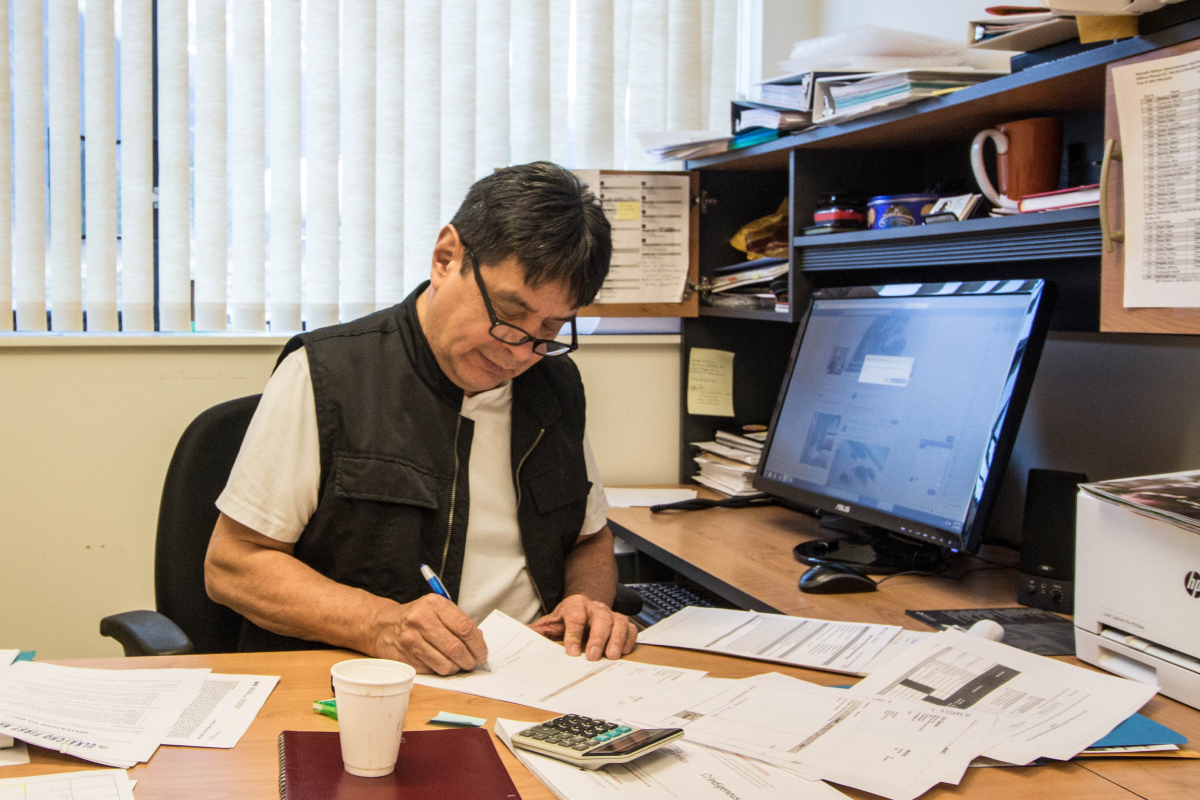

Richard Hall, 63, is a Red Seal carpenter (international standard of excellence for skilled trades), a certified building inspector and the community champion of the apprenticeship program. Hall lived away from Bella Coola for more than 15 years. Wally Webber, the chief at the time, was known to say, “I’m not a smart man, I just bring people who know more than me home.”

It took Chief Webber two years to convince Hall to come home and apply his knowledge as a carpenter and inspector in the community. Finally, after a “no-political-bullshit agreement,” Hall returned.

In his time as a Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation inspector, Hall inspected about 7,000 homes and buildings in B.C., on and off reserves. He explored the belly of the housing beast from the ugly inside-out. He saw third world conditions in what was supposed to be a first world country, he said in an interview one morning, seated behind a pile of paperwork in his office.

Hall left a residential school when he was 12 years old and like his parents and other family members, he said, he drowned out trauma with alcohol. One day, after years of being “the meanest person you could imagine,” he said, he faced two doors with two decisions written on them: life or death.

Hall chose life. Right then, he chose to live and vowed not to waste another day, he said.

Back in the day, like many of the men in his community, Hall was a commercial fisherman. If he wasn’t fishing, he was building houses and if he wasn’t building houses, he was logging. He was happiest out on the water though, out on the boat.

“It’s been too long since I’ve been fishing,” he said. Too long since he woke up with sore arms that don’t straighten, stiff from digging and scooping clams for four to five hours straight into the night.

When Hall logged, he worked 16 hours a day, six days a week. His wife raised their family while he was out making money to send home. This lasted until his grandfather pressured him go back to school. He resented it at the time, but would later accept it was the right decision.

An essential part of Hall’s work is convincing young Nuxalk men and women to do the same, to find something worth living for, to return to school, and to join the apprenticeship program.

In the spring of 2015, Industry Training Authority (ITA) Gary McDermott, then Director of Aboriginal Initiatives, introduced Hall to Olaf Nielsen, Susan Wilson and Larry Underwood in the special projects and trades department at Camosun College in Victoria. He proposed an apprenticeship program where students could study, train and work from Bella Coola. The team agreed to visit the valley and hold an information session to assess interest.

It takes a whole community to raise the bar

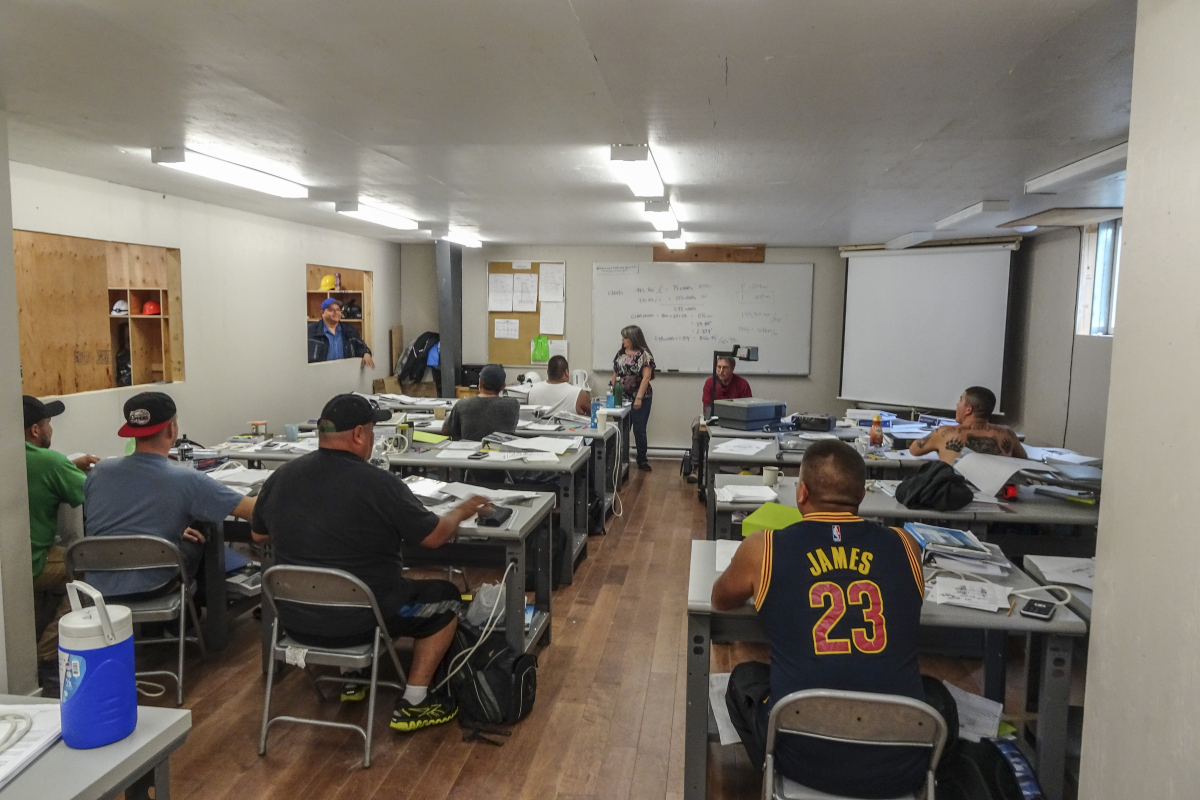

Larry Underwood and Susan Wilson, college coordinators, work specifically with Indigenous students in trades at Camosun College. They were amazed to see 30 interested students show up to the information session, an unbelievable surprise, for such a small community, they said. They knew then and there they wanted to work with Hall to make his vision a reality and get the four-year apprenticeship program off the ground.

Underwood and Wilson worked with the chair of the department, Nielsen, who told them to follow their passion and worry about the money later. The three worked hard to access funding streams for 16 apprentices. Nielsen secured about $5,000 for each student, through the Canada/BC Job Fund, through the Employment Services and Support Program and the Ministry of Advanced Education, for materials, instructors, classroom and shop space. Underwood and Wilson worked on tuition and book costs.

Wilson said she didn’t want to say no to any interested student, but strict eligibility requirements made access to funding nearly impossible for some.

“In order to be eligible, students cannot be attached to Employment Insurance (EI) and must work less than 20 hours a week,” she explained. Those requirements exclude many capable First Nations applicants, she said in an interview during a travel stopover in downtown Vancouver.

Both Wilson and Underwood are Indigenous and have committed their lives to uplifting other First Nations youth and communities. Underwood worked for years with the Coast Salish Employment Training Society, visiting communities and reserves across Vancouver Island. He said he saw a lot of the same housing issues that the apprenticeship program intended to address and he was inspired by the strategy of the Nuxalkmc's approach.

“There’s a lot of moving parts in Bella Coola,” he said. “It’s not just one person or situation, but a whole bunch of collaborative parts moving and working together for a common vision.”

Jalissa Moody, 27, is the band office’s asset assistant. She works tirelessly to support housing initiatives and watch her Nation grow in a positive direction.

Moody and Hall presented the apprenticeship program and some of the projects, a new restaurant, chief's building, fisheries office, and education building to the Nuxalk council. Triplexes and new larger homes were already being built, but Moody recognized a need for homes for single occupants, especially house-less men, couch surfing from house to house.

With a love for sustainability and eco-friendly technological solutions, Moody researched tiny homes, and wondered whether it was possible to spend the roughly $200,000-250,000 she estimated it would cost the Nation for one home in a different way, and use it to build four tiny homes. She created a proposal and presented it to council.

Council listened and approved her proposal. The four tiny homes are almost finished, solarized by Hakai Energy Solutions, with a shared fifth home with two washers and two dryers for all occupants’ use.

Another essential moving piece is council support, Moody explained during an interview while driving through the valley she and her ancestors have always called home.

Blair Mack is a council member who oversees the housing department. He said that for the apprenticeship program to get started, there needed to be a shift in leadership and a change in the traditional way of thinking about management and power.

The council has increasingly learned to grant managers more control over their projects, he explained. “The council approves, but the managers and the front-line workers are the ones who make it all happen,” he said.

Participants in the apprenticeship program also depend on the support of Theresa Brook, the education administrator of the Nuxalk Acwasalcmalslayc Academy of Learning.

Brook has spent her entire life in her Nuxalk territories and believes in the power of working together to move forward. “It takes a whole community to raise the bar,” she said, working in her office beside the Acwasalcta School that many of the community members helped build.

It's hard to imagine Brook without a smile. But she says she is often frustrated by all the paperwork and government bureaucracy standing in the way of getting access to funding. The Trudeau government has increased post-secondary funds for First Nations, she said, but she finds it difficult to constantly have to prove that the students are eligible for grants for trades and occupational work.

Love and Basketball

Allan Edgar is known and respected along the entire northwest coast. Some might know him as a skilled carpenter and journeyman, others will tell you he’s 60 and still sprints up on roofs and builds homes, while some still hold onto stories of his legendary basketball days, a status his son has inherited today.

Edgar is training Garrett Mack, whose in his second year of the carpentry program. The men were happy to take a brief break from work, have a smoke and reflect on the way the program has rippled throughout their community.

Edgar said that outsiders would cut corners and provide the minimum standard for buildings, because they weren’t the ones living in the houses they built. CMHC standards led to the disastrous approval of materials that were unsuitable for wet west coast weather, leading to an infestation of black mould in many homes.

Edgar said he was once a squeaky young boy, but now he roars like a grizzly, and he’s one of the loudest voices saying, “no more.” Now the Nation takes matters into their own hands, cutting out as many outside architects, consultants and engineers as possible. The work exceeds standards because of it, he said.

The apprenticeship program didn’t exist when Edgar was younger. He’s a Red Seal carpenter, but had to do his training outside the community, which was hard, he said, because he was away from family and people.

Mack, 28, agreed. His wife just gave birth to their first son. He’s in his second year of the carpentry program, living a hop and a skip away from where he apprentices and works.

“I don’t know how many guys Richard has saved,” Mack said. “He put us in the right direction or lined us up with a career choice, because a lot of us didn’t know what we were going to do.”

Mack said the program provides the apprentices security, direction and purpose, all key factors to feeding confidence and pride in their families and Nation.

Louis Edgar is Al’s son, and worked and trained with his dad for over 10 years. But he has earned his own reputation in the Nation and beyond. Louis is also a basketball star, having played in the All Native Basketball Tournament for years, as well as the World Indigenous Challenge. When Louis isn't playing ball, he's hunting or building homes, always pushing his body to the limit.

But he also commits mental discipline to his personal and professional work. Louis is in his second year of the carpentry apprenticeship program and first year of electrical. Taking a break from work in one of the triplex units, he offered a unique comparison of studying at home and abroad.

When Louis studied at Camosun College a few years ago, he said there were less distractions, so he could focus on his work, but that it was difficult being away from home. He volunteered countless hours as a tutor for other students. Humble like his father, this was a detail that Louis neglected to mention, but it spread throughout the community nonetheless.

At the end of his first year of electrical, he scored a 99 per cent on his final exam. He told his mother that he didn't get the last one per cent because he didn't have enough time.

When speaking about the apprenticeship program and how it has affected his life, Louis referred back to basketball.

“The stronger one person gets,” he said, “the stronger everyone grows.” Like dominoes, the success of one is the success of all. When one person gets empowered, they empower their family, their community and their Nation, he said. He thinks the program tunes apprentices into the bigger picture, the future of the Nation, not just the day’s work.

“My dad always says to visualize things. To see your shot going in,” Louis said. “I remember when I was younger, I’d get real frustrated with that, but he would say, it just comes over time.”

Tommy Walkus knows patience well. He learned the skill while he was studying art and English at Vancouver Island University, formerly Malaspina University College. He spent years in Nanaimo, making ends meet and wondering what he was going to do with his degree.

When the apprenticeship program came up, he jumped on board, apprenticing in both carpentry and cabinet joinery, where he gets to put his attention to detail to work. Walkus said he gets pride from being a part of a team that provides hope for his community.

The program has enriched the lives of all of the apprentices, some of whom had lacked confidence and made poor decisions, Walkus said. “There’s a light they carry now, instead of a darkness,” Walkus added, “Feeling that they’re needed is the most important thing.”

Carrigan Tallio is one of the only women in the program.

She was taught from a young age to believe in her abilities to be just as good as the boys. Tallio grew up spending most of her time on a boat, commercial fishing with her dad, who, until her younger brother was born, treated her like the “son he never had,” she joked.

Tallio always helped build and fix things around the house, but after high school, she jumped into a humanities program at the University of Victoria, thinking that a teaching career was one of the only options available.

Tallio said it was hard to be away from home. Like many of the others, she prefers smaller communities, where “everybody knows your name and keeps an eye out for you.”

Tallio was introduced to the program after she returned home.

The program’s funding meant Tallio could finance her 2016 Ford 150 truck and allowed her to train under her own family members. It wasn’t always easy for her though. At first, she was intimidated by the thought of handling power tools and keeping up with the men.

Every task she did boosted her confidence; her colleagues made her feel comfortable and safe and it wasn’t long before she stopped worrying.

“Times are changing,” she said with a smile.

In unexpected ways Tallio said she has found healing in the confidence and skills she builds as a woman in a male-dominated field. Beyond confidence and a vision for the future, Tallio also found love.

Tallio started working with fellow apprentice Dustin Newcombe in the first year of the program’s study group. She fell in love with his boisterous personality and humour. “It’s amazing to find someone I can build a life with, literally,” she said.

“I love it,” boyfriend Newcombe said, speaking about his girlfriend’s ability to hold her own. “She’s an outdoorsman and a hard worker.”

Newcombe has been working on a massive restaurant that will be equipped with a raised storage unit, a traditional smoker, a lounge and a beautiful view of the water from the back patio. The restaurant will serve traditional foods, prepared by a local Nuxalk chef and will be adorned in Nuxalk art.

Newcombe already imagines himself chilling in the lounge with his colleagues and buddies, remembering the beginning, remembering chipping away at the dream like the trunk of a tree, not yet a fully-carved masterpiece.

Moving forward with hope

Since the apprenticeship program started, the Nuxalk community has seen pride sweep through the valley as they rebuilt homes lost to fires, transformed old buildings and solved problems with sustainable solutions that ejected outside materials and employees.

The Nuxalk construction crew has minimized costs, maximized value and educated tenants about their roles and responsibilities in maintaining their homes. The crew uses wood finishing, LED lighting, radiant floor heating, mould resistant drywall, wood beams, siding posts and trimming and solid wood cabinets and countertops. They have designed and developed appropriate crawl and storage spaces, proper heating systems and new techniques to deal with unique weather conditions.

They have constructed new triplexes, six new tiny homes for single occupants, and a brand new restaurant. They also have plans to build a new bighouse, a ceremonial gathering space for potlatches and other social, political and cultural events.

All in all, the Nuxalk say they've created a recipe for success that creates a template that others can use. Now they hope to see it spread.

Moody said she would like to see a trades school in Bella Coola, where other First Nations apprentices could come and learn. That way, they wouldn’t have to study, isolated in a big city, but could visit a neighbouring Nation and maintain a sense of community. “Our community deserves the best,” Hall said. "Nobody knows our needs better than us."