Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

James Whitlow Delano had long regarded Instagram as a platform for mundane daily photography — pictures of “babies and what I had for lunch,” he used to say.

That was before he heard about the Everyday Africa Instagram account. It's a unique feed generated by Peter DiCampo and other photographers living in various countries across the continent. Every day, they post photos of life in Africa. Their goal is to disrupt the conventional narrative about a continent plagued by war, disease and poverty.

Something about the project captivated Delano, an American photographer based in Tokyo, who said he had been playing with the idea of starting a similar feed but about the environment.

He had been documenting climate impacts for several years, capturing billowing smoke from coal factories in China and the decimation of rainforest in Southeast Asia, for example. As such human activities contribute to rising global temperatures, climate change, he felt, was often forgotten.

“With all these other things going on in the world, climate change is kind of getting moved to the back burner but it’s a huge issue in this part of the world and I don’t think it’s being covered well enough,” he told National Observer in a phone interview.

After meeting DiCampo of Everyday Africa at a photography festival, Delano emailed him to ask if he could start a feed that would be part of the “Everyday family.”

Capturing the seriousness of climate change

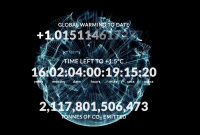

On the first day of 2015, Delano started “Everyday Climate Change,” an Instagram feed featuring powerful photos of climate change impacts and damage from pollution. The images include a picture of flip flops and plastics littering a marine reserve on Kenyan shores. There's another one of a young boy in the Philippines sitting down in the middle of a village destroyed by floods.

Each photo comes a network of more than 30 photographers. They help provide explanatory texts that Delano fact checks before publishing. He said the fact-checking is particularly important in an age when people are more skeptical about fake news reports and the misleading use of photos out of context.

“To create this feed was to show how serious this issue of climate change is and how it’s affecting people’s lives already and we have to get serious about this,” he said.

He remembers a pro-Donald Trump post showing a wall reported to be on the Mexico-Guatemala border with a text asking why it was racist for Trump to build a wall on the U.S.-Mexican border, but fine for Mexico to have its own wall with Guatemala. The photo actually showed the West Bank wall separating Israel and Palestine.

“The misuse of photography can be quite powerful,” said Delano. “It’s important that we get it right because people are beginning not to believe their own eyes... We have to be very careful to be honest and forthright and careful about what we assert.”

Delano also hopes that the social media platform, owned by Facebook, will reach people who don’t access traditional media on a regular basis. Instagram said in September it had 800 million users and 500 million of them used it every day. In the United States, 59 per cent of Internet users between the age of 18 and 29 used Instagram in 2016 according to Pew Research Center.

“We’re able to get out of the cloistered media, journalism world,” Delano said. “It’s a wonderful way to reach people all over the world without tremendous investments of funds.”

He received responses from people seeing photos from the feed in Australia, Ukraine, the United States, Singapore and South Africa. Instagram said in 2016 that more than 80 per cent of its users lived outside the U.S.

Building a kindred spirit across borders

“It’s being noticed and I hope people are coming together in a way as a global community,” he said. “For me, it’s about building a kindred spirit across borders.”

While Delano worries about sounding “too naive,” after decades of travels reporting on climate change, he has realized climate change can impact on people no matter where they live. He wants to build empathy and unity with his photos.

“Frankly, once you know somebody it’s harder to think of them as 'the other' and we’re all in this game together, it’s a transnational challenge,” he said.

Nearly three years since after it launched, the feed has about 2,000 posts and more than 100,000 Instagram followers.

Delano’s effort to raise awareness about climate change is not limited to the virtual space either.

“We’ve begun going to schools and do presentations in various cities and I’d like to do more of that,” he said.

But as a photographer, he believes his main tool in tackling climate change is visual.

“I'm always thinking of how can you communicate in one frame some of why climate change is important," he said.

Comments

Hi!

Post your profile! Become one of our pro photographers team on https://photolions.com