Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Indigenous Services Minister Jane Philpott is hoping to deliver more health care closer to northern Indigenous communities, in order to address a crisis leaving Inuit women vulnerable in southern cities like Montreal.

Speaking to National Observer in an interview, Philpott said a combination of better addictions treatment, remote medical technology, funding for travel companions, training for midwifery and cultural sensitivity and a shift to Indigenous delivery models can help to address some of the tragic health outcomes.

“I think it needs to be addressed from multiple angles,” she said March 1, moving from “the current approach, where people often do have to leave from communities to get care far away from their homes — (to) the longer term approach of how we can actually improve the opportunities for people to get high-quality health care services much closer to their communities.”

Each year, thousands of residents of the Canadian Arctic fly thousands of kilometres to obtain health care services. National Observer has documented how the punishing cultural and physical disorientation that comes with these commutes can leave travelers alienated, vulnerable to addiction or rape, or dead.

Organizations such as the Native Women’s Association of Canada say Inuit women on medical commutes face language barriers, discrimination and the culture shock of sprawling urban centres. Last month, a public inquiry in Montreal heard that bias, racism and discrimination is rampant for Inuk women in Quebec.

'Significant gaps' in Indigenous health

In a story last year, Montreal-based reporter Selena Ross followed the life of a woman identified as Leah who travelled back and forth from Kuujjuaq, Nunavik, to Montreal to give birth to seven children. She was raped at seven years old, began using drugs at nine, and got pregnant at 13.

In Montreal, she became involved with an abusive boyfriend and got pulled into street life, with its pimps and drug dealers. Four of her children have been adopted or fostered — including her baby boy who was seized by social workers shortly after delivery because crack had been detected in his blood.

Last week’s federal budget acknowledges there are “significant gaps in health outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people” in terms of infant mortality rates, diabetes and suicide.

Philpott has also spoken about the gap and its link with intergenerational trauma, racial discrimination and the social determinants of health such as education and housing.

The budget provides $400 million over 10 years for housing in Nunavik and other Inuit regions to “address significant overcrowding and repair needs.” It also contains a $200-million commitment to “enhance the delivery of culturally appropriate addictions treatment and prevention services in First Nations communities.”

The minister mentioned an expanded addictions treatment centre in Kuujjuaq in the context of this funding, although she said the government has yet to decide how the money will be spent.

“They’re doing some really fantastic work around providing support for substance-abuse disorders, where people can actually bring their families in to a treatment program with them,” she said.

She also pointed to the government’s policy change last year to fund non-medical escorts for medical trips. Funding in the 2017 federal budget provides for $108 million over four years to expand a health investment fund for Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut.

“When we came into government, the policy was that they had to go by themselves,” said Philpott.

“You were seeing 15-year-old girls sometimes going thousands of kilometres away from home, to cities like Winnipeg and Ottawa, to give birth entirely by themselves — no support of a family member. You can only imagine all the trauma that’s associated with that.”

Even so, she said the extra funding has introduced “new challenges” — women in remote parts of Nunavut going to Iqaluit with companions means more accommodations in that area needed to be expanded.

Nunavik itself has a regional board of health and social services, and provinces in general have jurisdiction over health care. Philpott said she wasn’t sure of the specifics of Leah’s case, but acknowledged there are challenges in cross-jurisdictional authorities for health services.

'Culturally-safe midwifery,' remote care

Kaummajuk (Holly) Jarrett, Inuit policy and protocol advisor at Native Women's Association of Canada, said information on local services and documentation is often in French in Montreal, while Nunavimmiut — Inuit from Nunavik — speak mostly Inuktitut and English.

The experience is “personally and culturally overwhelming,” said Jarrett.

“These people are leaving remote geographical areas, and upon arrival to these sprawling urban cities, are enveloped in a shroud of culture shock. For most, it is the first time away from areas that do not have more than a few streetlights — let alone bustling sidewalks and concrete walls of office buildings.”

Philpott mentioned last year’s five-year, $6 million budgetary commitment to “culturally-safe midwifery in communities,” part of its maternal and child health funding.

She added the government can work with universities and health care professionals on better cultural sensitivity training, so non-Indigenous care providers understand the backgrounds of the patients they’re serving.

“There’s a huge need to address that, because of the stigma and discrimination that Indigenous people often face,” she said.

She also said remote healthcare technology, which has been deployed in the north of Newfoundland and Labrador, also holds promise. “It’s been shown that you can actually provide good or even better care remotely, using these technologies,” she said.

Finally, the 2018 budget contains funding for First Nations health systems to begin expanding “successful models of self-determination.” Philpott said that was critical in the long-term.

“We know from experience that health systems improve better for Indigenous people, if they are designed, controlled and managed by Inuit, for Inuit, or by First Nations, for First Nations,” she said.

Inuit population rising, including in Montreal

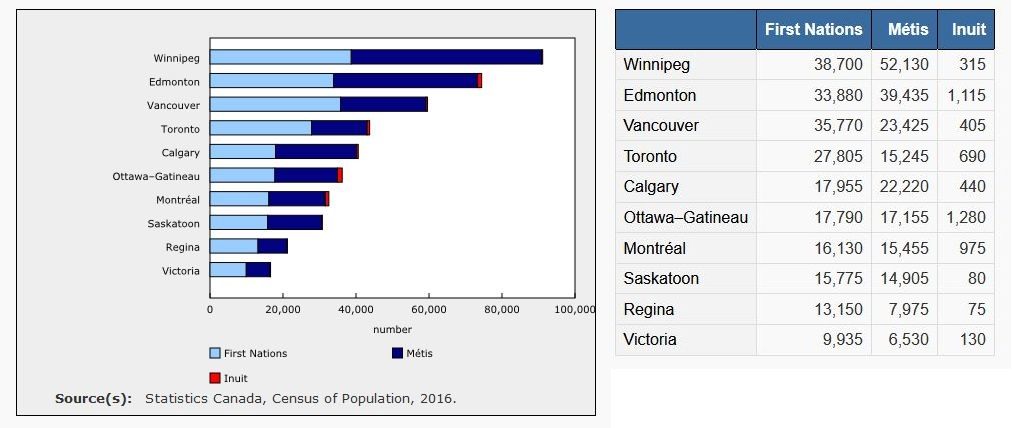

The Inuit population has been increasing rapidly over the last decade. Statistics Canada shows that from 2006 to 2016 the Inuit population grew by almost 30 per cent, and now stands at 65,025.

The Inuit population in Montreal also grew by hundreds of people. The 2006 census showed an estimate of between 400 and 599 Inuit in Montreal; the census a decade later says there were 975.

That means that, out of the major metropolitan areas in Canada, Montreal is now home to the third-largest Inuit population, after Ottawa-Gatineau (1,280) and Edmonton (1,115). Toronto comes in fourth, at 690.

Jarrett argued the rise in Inuit population in Montreal is not due as much to planned relocation, as to Inuit traveling to Montreal for medical care and becoming stranded.

“If a flight back to the home community is missed, there is no ‘make good’ flight allowed. The person then must fend for themselves to find enough money to pay for a new flight," she said.

"This is nearly impossible for most, and they become one of the ‘left behind’ and must survive on the streets.”

Patients in the Nunavik region are now sent to the Ullivik patient home in Dorval, which opened its doors last year.

The Makivik Corporation, which has a mandate for Inuit in Nunavik, contributed an Inukshuk in the front of the building. Stephen Hendrie, a spokesman for Makivik Corporation, said the story in media might be about hardship, but the centre demonstrates that hard work is being done.

“The centre...does provide all kinds of facilities to make sure that if patients are coming down and they only speak Inuktitut, that there’s interpreters — and that interpreters go with the patients to the hospital for treatment,” he said.

“It’s in an area [that] is actually closer to the water, closer to the airport, so people are not getting lost...from our perspective, it’s a big leap forward.”

Comments