Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

The place we call British Columbia is home to 60% of all Indigenous languages in Canada- with 34 distinct languages and over 61 different dialects.

Language is at the heart of any culture. It is more than just a set of words and rules. It defines the way you dream, think, communicate, understand the world– and your and everyone else's place in it. Some words or concepts in one language can never be fully understood or defined in another.

In a newly released book on the Haida language, That Which Makes us Haida, elder GwaaGanad (Diane Brown) said: "Our connection to the land, when you hear it in Haida, it's much more direct and clear; you can understand our relationship better. Haida is more intimate."

On his popular social media account, influential Nipissing Anishnabe public speaker and former D.J. with a Tribe Called Red, Migizi Bebaayaad (Ian Campeau), shared his experience learning his language. "I recently learned the days of the week in my language. I was surprised to learn they’re mostly named after Christian words - like Friday is Jiibiiyaatgooghizhiigad or literally 'Cross Day,'" he wrote.

"I asked my aunty what the days of the week were named before contact. My aunty taught me that we didn’t have names for the days of the week pre-contact. Every day had its own name and life cycle. It was “snowy” (zookpo) or “windy” (Noodin) or “cloudy” (gwaankwad) day. Each day had its own “spirit”. It’s weird that we’re forced into a seven day cycle named after Norse Gods where we can arbitrarily compare this Tuesday to last Tuesday."

"It’s meant to control our time to contribute to capitalism."

Wade Davis, a Canadian anthropologist and advocate for language preservation often says, "Every language is an old growth forest of the mind, a watershed of thought, an ecosystem of social, spiritual and psychological possibilities. Each is a window into a universe, a monument to the specific culture that gave it birth, and whose spirit it expresses."

Canada's government of yesterday recognized the inherent powerful connection between Indigenous languages and cultures and attempted to eliminate them because of it. Indigenous languages were forbidden and children were severely punished for breathing life into their mother-tongues. In today's era of making things right, today's government has committed to the revitalization of Indigenous languages and cultures.

On February 20, B.C. Finance Minister Carole James delivered the 2018 budget at Legislature in Victoria. “We are committing $50 million this fiscal year to support the preservation and revitalization of Indigenous languages in B.C.,” she said.

In her speech, Minister James echoed language experts who say language is fundamental to who a person is, where they come from, how they relate to others and what will live on after they are gone. She cited the government’s loyalty to the Truth and Reconciliation’s 94 Calls to Action, six that refer to the importance of preserving Indigenous languages in Canada.

Minister James also reiterated Canada’s support for the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). The UN Declaration includes articles on rights to Indigenous languages (Article 13), rights to controlling and establishing education systems on languages (Article 14), rights to cultural heritage (Articles 11 and 13) and rights to media in Indigenous languages (Article 16).

News of the newly-amped provincial funding came as a relief to Tracey Herbert, and others who have dedicated a large part of their lives revitalizing First Nations languages in B.C.

"This to me is one of the most significant steps towards the implementation of the TRC and UNDRIP, all over Canada," Herbert said.

Herbert is the CEO of the First Peoples Cultural Council (FPCC), the third-party organization charged with managing and distributing the $50 million across the province. The FPCC is a provincial Crown Corporation established in 1990, supported by the First Peoples’ Heritage, Language and Culture Act.

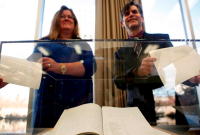

I met with Herbert at the Royal B.C. Museum to tour the 'Our Living Languages Exhibit,' discuss what the FPCC has in store for the newly announced funding and hear about why First Nations languages are worth the fight.

Our Living Languages Exhibit

The ‘Our Living Languages’ interactive exhibit first opened in 2014 with a plan to remain open for three years. Its success, including a 2015 win in the American Alliance of Museums Excellence in Exhibition competition, has kept it open well past the date and into the future. The exhibit is meant to educate participants about the history and diversity of Indigenous languages in the province.

B.C. is home to 60% of all Indigenous languages in Canada. There are 203 First Nations communities in the province, with 34 languages and over 61 dialects. The exhibit gives a taste of this diversity, inviting participants to walk through the “language forest,” to hear greetings in the 34 languages, learn about where languages are located and how many fluent and semi-fluent speakers exist in each area.

A language cocoon, woven like a cradle, invites participants to hear stories and lullabies by elders and children, meant to offer a glimpse into what full language immersion could feel like.

“Think of the term mother-tongue,” Herbert said, as we sat in the cocoon, lights dimmed, children's voices laughing and lullabies echoing around us. “The languages we grow up with are our kin, our nourishment and our birthright.”

The exhibit showcases snaps of history about how Indigenous languages were prohibited with a strong colonial intention of total elimination, but Herbert said the space was meant to be more positive and forward-looking.

“We’re shifting our relationship to our languages - from negative - to finding our voices and moving forward, with our own view of our languages and why they’re important,” Herbert explained. “We’re moving away from the deficit narrative. We don’t often hear our voices, in institutions like these, where others are representing us. We need to represent ourselves and have our voices heard.”

Herbert said the exhibition is meant to give Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples the chance to interact with Indigenous languages. It's a way to communicate the importance of preserving the diversity of languages in the province.

Institutions, systems and governments have subjugated Indigenous voices from the conversation for so long, that Herbert said she's not confident that they know how to treat Indigenous people as equals. But the exhibit, she said, is a strong model of two organizations working together as equal partners, with equal voice at the decision-making table.

“That’s why you hear Indigenous voices here,” she said.

As we settled into the lobby of the museum, Herbert spoke about how she first came to work for the FPCC. She was attracted to the organization first because of its arts mandate, but was immediately inspired by the motivation of elders to preserve their Indigenous languages.

"I met this one elder in particular, who was explaining to me that she had broken her collar bone," Herbert said. "She was supposed to be off work for six weeks, but went back after two, because there was nobody else to teach the language. The women I met were so committed to the language work and I thought, I have to do what I can, to support this work."

Herbert said the FPCC took a turn for the better in 2006, when the organization started to focus on more immersion activities, to create more speakers, and focus more seriously on language documentation. Prior to 2006, the organization was invested in awareness building, which is important, Herbert noted, but doesn't create new speakers.

“We’re moving towards multi-year projects, instead of one-offs,” she said. “We also want to set some hard goals: How many speakers do we want in five years? How will we do that? We want to establish some good plans, so we can track and measure how we’re doing over the next five years and see exactly what we need to incorporate.”

The FPCC delivers a variety of programs and projects, including First Voices, an Indigenous language archiving and teaching resource. They conduct research on a regular basis and write reports on the status of First Nations languages. Herbert said the council has been trying to educate policy makers on the benefits of bringing back Indigenous languages and strengthening communities.

They administer a number of immersion programs in First Nations communities; a Mentor-Apprenticeship Program, Language and Culture Camp, Language Nest Program and Language Revitalization Planning Program, each with their own unique methodologies and outcomes. They have piloted many programs, including a silent speaker program, and with the new money, they’re able to fund it.

“We have people in communities that completely understand the language, but don’t speak it, like my mother,” Herbert said. “She can tell me what everything means, but can’t speak it, because of a block. She would be a perfect candidate for the silent speaker program.”

Herbert said the two pilots of the silent speaker program were transformative. Elders were able to release and let go in a safe space and to create self-awareness around their barriers.

“Healing is an important component to the work we do,” Herbert said.

Moving forward, Herbert said the FPCC has specific objectives they want to achieve, like the documentation of all 34 languages, creation of new speakers, and specific language plans for each language. There’s flexibly from community to community, she said, because each group are at different stage, but the council works with the language experts of each community to determine the best approach.

“The funding will be by proposal for now, but we want to transition into a time when we’re funding plans, not proposals, so we can deliver more long-term sustainable funding,” Herbert explained.

The FPCC is comprised of a Board of Directors with up to 13 members, a 34-member Advisory Committee (one seat for each First Nations language in B.C.) and a peer review committee.

Herbert said the Board of Directors, comprised of people who have both board experience and language expertise, provides strategic direction. The advisory committee provides input on programs, strategies, policies and communications. Any First Nations person living in B.C. can apply to be on the advisory committee. The peer review committee, made up of Indigenous language experts, or Indigenous artists in the field, are the ones who review proposals and make recommendations for funding.

Herbert said the FPCC will work to provide regional coaches for proposals and funding, to help communities move forward with the planning piece.

“Successful language revitalization looks like multi-strategies at the same time, multiple domains and multiple graphics,” she said. “That’s why the revitalization piece costs money, because we have to do it in so many places, for it to catch hold and be successful.”

Though not every community may be ready for a specific program, the least the council can do is fully document the language, own and curate the data, so it’s there for “that inspired family or individual that wants to take on the challenge of bringing it back,” she said. "It can be done. We've seen it over and over."

The FPCC is directed by Indigenous voices, Herbert said, which defines their values of accountability, transparency, results-based initiatives, collaboration and integrity. FPCC works in full partnership with communities, and work with the Canadian government to provide more opportunities for language learners.

Some have criticized B.C.’s recent funding announcement, but Herbert said Indigenous people can’t let outsiders and policy makers decide whether or not our languages survive. Language is connected to who you are, where you come from, your history, values, your point of view, how you conduct yourself in the world. "It’s all there in the language," she said.

“My dream is that it will be more accessible for those with the desire to learn to learn,” Herbert added. “Why can’t you do an online course with an elder from your home territory? Hopefully within the next five years, we’ll have more access from all over. We have quite a migratory population, but wherever you are, you should at least be able to access your language.”

Though online access is important, and an essential step in the right direction to revitalization, Herbert said full-immersion programs, with one-on-one relationship are most successful.

“People who taught for 20 years, after learning the immersion methodology, couldn’t believe how easily people were picking up the language,” she said. “We have all these semi-fluent speakers now. The strategies and methodologies for teaching are really important.”

The FPCC looks to other successful Indigenous language programs and strategies for inspiration. They look to Indigenous languages in New Zealand, Australia, Wales, Ireland, Israel, Japan, Hawai’i, as well as techniques used across North America.

“Brian Maracle has had amazing success. The Mohawks are doing so well with their language. He has been doing it for 15 years,” Herbert said. Maracle established a full-time adult immersion language school, Onkwawenna Kentyohkwa, in 1998.

Herbert also noted Dr.Darrel Baldwin's work. Baldwin, from the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, is an Indigenous linguist and revitalizationalist for the Myaamia language.

"He reclaimed a language that had no speakers left," Herbert said. "He now has programs and an institute that are bringing the language back. It's all about committed individuals and communities that want the language. Our role is to support their work."

"There are pockets of really good work, despite a lack of support," Herbert said. “When I started in 2003, we had $1 million or less a year for our whole budget. But even though our organization hasn’t always had a lot of funding, we have still been able to strengthen our advocacy and mature as an organization."

The Department of Canadian Heritage is the federal government body responsible for allocating funds for Indigenous language revitalization. Tim Warmington, the department's media spokesperson, wrote in an email that in 2017, the federal Aboriginal Languages Initiative (ALI) rose from $5 million to approximately $19 million annually.

"It was the first reinvestment for Indigenous languages in more than a decade in Canada," he wrote.

He said the department will allocate $3.6 million for the next two years to the FPCC. But Herbert doesn't think this amount shows that the federal government is committed to B.C.'s diversity of First Nations languages as the province has put forward.

"$3 million divided by 34 languages isn't a significant response to date. I'm hopeful the legislation of new funding will come, but it's unfortunate they couldn't have bumped it up more," she said.

"We're calling for reconciliACTION- to take action, rather than pulling people together to just talk about what we can do."

Budget 2017 proposed to invest $89.9 million over the next three years to support Indigenous languages and cultures. Warmington said this includes $69 million to enhance the Aboriginal Languages Initiative- learning materials, language classes and culture camps, as well as archiving. $14.9 million will go to support Library and Archives Canada and $6 million for the National Research Council Canada.

"They gave a lot of the money to the National Archives Canada and the National Research Council," Herbert said. "They gave $20 million right off the top, rather than to Indigenous communities. They are forming committees and do want to work, but that's quite a bit to take off the top."

Only time will tell whether the government's commitment to righting wrongs and revitalizing Indigenous tongues is efficient. And when it does tell the tale of this era, hopefully it will do so in plethora of Indigenous languages that have articulated the laws of the land since time immemorial.

Comments