If history repeats itself...

Has Canada made itself vulnerable to a catastrophe on the scale of the Deepwater Horizon?

An investigation by Joel Ballard indicates there is reason to believe that's exactly what Canada has done.

As a huge BP oil rig began drilling into the Scotian Basin, 300 kilometers off the coast of Nova Scotia, Environment and Climate Change Minister Catherine McKenna was picking plastic off a beach near Halifax to promote Earth Day 2018.

McKenna had given her stamp of approval to BP's offshore oil exploration earlier that week.

The new BP rig floats near to two crucial habitats. Sable Island National Park Reserve is its closest neighbour sitting 48 kilometers from the drill site, and the Gully Marine Protected Area is 71 kilometers away.

The two ecosystems, home to a vast array of life including northern bottlenose whales, rare corals, and the famed wild horses of Sable Island, are vulnerable to a spill due to their proximity to the site.

Also vulnerable to oil spills, increased underwater noise pollution and the potential of being struck by BP ships, are the few remaining North Atlantic right whales. This docile surface skimmer is already among the most endangered of whale species. The population isn't having babies and at least 17 whales died in Canada and the U.S. last year, many from entanglement with vessels and fishing gear.

Experts are warning of "extinction," and the Canadian government had vowed to take "every possible measure" to protect the whales.

Could Canada have done more to protect the ocean and coastlines by holding BP to the same standard for offshore drilling safety as countries like Australia and the U.K.? That would have meant requiring BP to house a "capping stack" near the new drilling site. These 130 tonne steel giants, covered in tentacle-like pipes, were developed to seal the kind of underwater spill that decimated the Gulf of Mexico in 2010.

As things stand, the nearest one is a two-week Atlantic crossing away, in the coastal city of Stavanger, Norway.

Canadian bureaucrats reviewing the project initially asked for a capping stack to be kept nearby but BP pushed back and Canada relented.

National Observer found that when Australia required an on-location capping stack for proposed drilling in their Great Australian Bight, BP withdrew its application. In other regions, like the North Sea, governments require capping stacks nearby.

BP plans to drill twice as deep as the ill-fated Deepwater Horizon disaster. In order to better understand the risks to Canada's east coast, National Observer:

- Spoke with an expert in catastrophic risk management who warns that the government's conditions for approval were too lax, even 'ignorant'

- Interviewed a fifth-generation fisherman who fears his way of life will be lost forever

- Obtained documents that state it could take BP Canada anywhere from 13 to 165 days to stop a well from leaking 25,000 - 35,000 barrels of oil per day into the ocean with the capping stack stored in a faraway Nordic warehouse

Here's what we learned.

"It brings a chill to my blood"

“It’s ignorance. A lack of knowledge of what other countries have done in very similar circumstances," warns Dr. Robert Bea

Dr. Robert Bea, leader of the Deepwater Horizon Study Group and co-founder of the Center for Catastrophic Risk Management says the BP project comes with some alarming risks for Canada that show that lessons from past oil disasters haven't been learned.

“We need to benefit from our painful past,” warned Dr. Bea, referring to BP’s Deepwater Horizon disaster, where he worked as a post-blowout investigator.

The Macondo well (Deepwater Horizon) spill was the largest marine oil spill in history and is estimated to have leaked around 3.19 million barrels of oil into the ocean for 87 consecutive days.

“Caution is warranted,” urged Dr. Bea.

Would other countries known for strict offshore drilling regulations have green-lighted a proposal like the one approved by Canada?

“No.” Dr. Bea's response is immediate. “And notice how quickly I came to that answer. There’s no way.”

The Berkley University Professor Emeritus has spent the past 64 years working in the oil industry and said that, based on his research, the BP project fails to pass an almost universally used test.

The test, based on a system developed by the U.K Health Safety Executive, is designed to determine whether a project meets the minimum threshold of 'As Low As Reasonably Practicable (ALARP).'

National Observer reached out to both BP Canada and the Canada-Nova Scotia Offshore Petroleum Board (CNSOPB), the regulatory body responsible for approving the project in Nova Scotia, to find out whether the proposal had been put through the test. Stacy O'Rourke, director of communication for CNSOPB, said "We take into consideration global industry standards used in similar operating environments," but would not provide a specific answer. BP Canada spokesperson Maureen Herchak encouraged National Observer to have a look at CNSOPB's website "to review at your convenience to understand the rigorous requirements that were satisfied to obtain approval."

National Observer's review of the site found no mention of ALARP or any similar tests.

How long would it take to stop a spill?

“The project poses a significant risk to our environment,” said Ecology Action Center marine conservation officer Travis Aten to National Observer.

Currently, Canada does not have a capping stack — the aforementioned yellow, tentacle clad, steel giant — an important piece of equipment that is used to cap an underwater well that is leaking oil into the ocean.

If any of BP Canada's deep-water wells spring a leak, like the Deepwater Horizon disaster in the Gulf of Mexico, Canada would have to transport the 130,790 kg capping stack from a warehouse in Stavanger, Norway.

“It would take a minimum 12 to 14 days to get that from Norway to here, and that's if the weather conditions are okay,” warns Aten.

The CNSOPB confirmed the length of the trans-Atlantic journey. However, the board stressed that the capping stack would only be needed in the "unlikely" case that the blowout preventer failed. Unfortunately, in the case of Deepwater Horizon, that's exactly what happened.

O'Rourke told National Observer the first step would be "the deployment of a remote operating vehicle to the ocean floor to latch on and manually activate the blowout preventer to seal the well and, if successful, would then negate the need for a capping stack."

In their own assessment, BP Canada predicts that the capping stack’s journey could take anywhere from 12-19 days based on weather conditions. Once on location, they claim it would take between 24 hours to 13 days to cap the well, resulting in a continuous underwater oil spill off Nova Scotia for up to 32 days.

Dr. Robert Bea sees BP Canada’s estimations as blithely “optimistic."

“It brings a chill to my blood," he said. "If there’s a blowout in the wintertime with the North Sea blowing and going, are we going to be able to get a capping stack from Norway to Halifax in 30 days? Hell, no.”

Correspondence between the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency and BP Canada shows that the location of the capping stack in Norway was a concern to Canada's authorities, as well.

In two different documents in 2017, bureaucrats ask BP Canada why they can't keep a capping stack in Atlantic Canada instead of Norway to permit quicker emergency deployment:

Somewhat incredibly, British Petroleum — less than a decade after causing the worst oil spill in world history — replied that capping equipment is "rarely (if ever) used." BP Canada further stated that because of the steps needed to prepare a well for a capping stack, “there is a low likelihood that changing the location of the primary capping stack would significantly reduce the total mobilization and installation duration.”

After BP's third response, the documents show that Canadian officials had stopped pushing for a capping stack to be stored locally in Eastern Canada.

National Observer asked numerous questions about the BP approval process and requested an interview with Minister McKenna through her ministry of Environment and Climate Change on several occasions in late April and early May, but did not receive answers to the questions before publication.

However, the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency provided a statement saying, "On February 1, 2018, the federal Minister of Environment and Climate Change determined the proposed Scotian Basin Exploration Drilling Project is not likely to cause significant adverse environmental effects and may proceed, in accordance with the legally enforceable conditions set out in the environmental assessment decision statement."

What about drilling a 'relief well?'

A capping stack is used to treat blowouts at the sea floor but if there is a leak lower down, BP Canada would need to drill a relief well, a process that they predict would take 165 days.

Again, Dr. Bea found that BP Canada had quoted best-case-scenario numbers.

“It’s a reasonable estimate if you had a drill rig nearby but if you have to bring the rig from someplace else, then no [it would take much longer].”

On April 26, National Observer asked BP Canada if they had a second drill rig on location but the company did not provide an answer.

Dr. Bea believes the project was approved due to a lack of experience in dealing with offshore drilling in Canada.

“It’s ignorance,” he warned. “It’s a lack of knowledge of what other countries have done in very similar circumstances."

Local fishermen worry that an oil spill could signal the end of a way of life

“We don’t hold animosity against these oil companies. For us, the fault lies with the government and the regulators," said lobster fisherman Colin Sproul.

Colin Sproul is a fifth-generation lobster fisherman whose family has been working the same wharf, in the same community for the last 200 years.

“If you’re a Nova Scotian, you belong to the sea," Sproul said. “We all connect ourselves to the sea through the food we eat and our cultural identity. It’s so important to who we are as a people and we are horrified to see it put in jeopardy.”

It’s a way of life Sproul wants to preserve, especially so he can pass his net — and traditions — on to his son.

That's one of the reasons he is so angered by the government’s decision to approve exploratory drilling “without reasonable environmental controls and appropriate spill response measures.”

“We don’t hold animosity against these oil companies," he said. "For us, the fault lies with the government and the regulators. They’ve totally abdicated their responsibilities.”

The 2010 Deepwater Horizon spill is estimated to have cost the U.S. fishing industry between $51.7 and $952.9 million in total sales, according to a report by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management. Sproul worries what a spill of that scale might do to Nova Scotia's fishing industry.

“It would mean economic ruin for all our communities,” Sproul warned. “An end to a way of life that my family has practiced since we came here and carved out an existence.”

As part of the federal Oceans Protection Plan, and in an effort to save the North Atlantic right whale, Atlantic Canada has already seen the closure of some its most lucrative fisheries due to the endangered species getting tangled - and sometimes dying - in fishing nets.

Sproul is the Vice President of an association of 175 small-scale, family-based, sustainably-minded fishermen. He says his colleagues could accept the closure of their traditional fishing grounds in order to preserve the species. But the government's stance toward BP has them asking why they're the only ones being asked to sacrifice for the ocean's health.

“Why should I give up an area that I fished with my grandfather? Why should I spend my money to protect an environment which is ultimately being placed in much graver danger by the same government that is forcing ocean protection on us?” said Sproul, echoing the concerns he hears.

He believes the Government is “using the East Coast as a scapegoat to achieve an aura of environmental responsibility and it’s wrong.”

In 2017, Nova Scotia’s fishing industry brought in $2 billion dollars in exports, while offshore drilling royalties produced $1.9 billion over the last 16 years, a statistic the proud fisherman is eager to relay. Given these numbers — and their generational knowledge of these waters — Sproul wonders why fishermen have never been invited to participate in any meaningful discussion.

“It’s easier to bring energy projects to fruition if you use proper consultation from the start. And eventually, they [BP Canada and the CNSOPB] need to learn that.”

He fears that an error onboard BP’s offshore installation could change the course of Nova Scotia forever.

“We have the right to ask for simple protections like a capping stack on site and preparations to drill a relief well,” said Sproul.

Lingering effects of Deepwater Horizon

The long-term effects of the BP Macondo spill on the environment are still unknown, however; Reuters reported in 2015 that "from 2002 to 2009, the Gulf averaged 63 dolphin deaths a year. That rose to 125 in the seven months after the spill in 2010 and 335 in all of 2011, averaging more than 200 a year since April 2010."

It's estimated that 600, 000 to 800, 000 seabirds died as a direct result of the spill and coastal communities struggled as large areas of the Gulf of Mexico were closed to commercial and recreational fishing.

As Gretchen Fitzgerald, the National Director for Sierra Club Canada, sat at her computer watching satellite imagery of the oil rig slowly coming closer and closer to Nova Scotia waters, she could feel a sense of dread build up inside her.

“This whole package just resonates with so many problems about how we take things for granted until, unfortunately, in the case of the Deep Water Horizon, it’s too late," said Fitzgerald.

BP Canada's site on the Scotian Basin sits 48 km to the south of Sable Island National Park and 71 km away from Gully Marine Protected Area, two government-protected habitats that support a variety of wildlife, including the world’s largest breeding colony of grey seals and two species of endangered sea turtles.

Clinging to boulders on the slopes of the gully is a kaleidoscope of colour, the largest variety of cold-water corals in Atlantic Canada.

If oil were to spill into the ocean, BP has proposed to use a chemical dispersant called Corexit 9500a, a plan Sproul calls the worst possible scenario as it would cause the oil sink to the ocean floor, covering “the very corals that the protected area is meant to protect.” The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) confirms Sproul's fears in a report showing that when corals come into contact with oil, it can kill them or alter their individual and reproductive development.

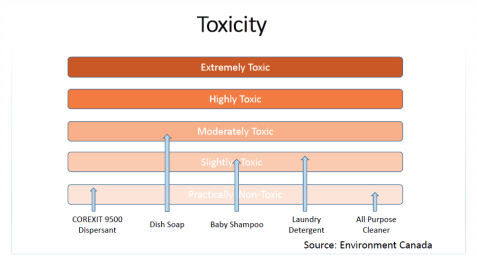

Recently, The CNSOPB has been circulating handouts that compare Corexit 9500a to "baby shampoo" in terms of toxicity, according to an article by The Energy Mix.

The handout fails to mention that when Corexit 9500 mixes with oil, it makes the oil 52 times more toxic to marine plankton, an important player in ocean's food chain, according to a study by Science Direct.

In the event of a spill, the government appointees on the CNSOPB would determine whether or not to approve the use of a dispersant.

In Canada's Environmental Assessment of the project, they say they'd grant permission "should it be determined that the trade-off between the potential toxic effects of the dispersed oil in the water column relative to the advantages of removing oil from the sea surface and preventing environmental effects on shorelines are acceptable for their use."

The same federal assessment confirms Fitzgerald's concerns about whales and the environment: there will be "an increased risk of mortality and injury to wildlife" due to auditory damage from underwater noise pollution.

“Knowing we’re taking the risk when we shouldn’t be and we’re not even doing the best we can to protect marine life and other industries increases that sense of dread,” said Fitzgerald.

Concerns grow over regulating board's perceived bias

Nova Scotia's coastline stretching out into the sea. Photo by Brian Lamb

“Sure, it doesn’t happen every day," said Fitzgerald. "But we are rolling the dice when we know for a fact that we’re not ready.”

Fitzgerald argues there are significant weaknesses in the government's regulation process for offshore drilling. In particular, she questions how the CNSOPB can effectively regulate oil companies when they are made up entirely of "oil industry insiders."

The board consists of five appointees and currently includes the founder of The Maritimes Energy Association, the former Vice President of Resource Development for Nexen Energy, and the Chairman of the Board for Calgary-based Sproule.

“You have that bias. You are from that world. It’s hard for you to balance that expertise with environmental protection or another industry’s perspective, ” said Fitzgerald.

Her concern over potential or perceived bias was an issue echoed by the Bay of Fundy Inshore Fishermen's Association.

When National Observer reached out to the CNSOPB to discuss the makeup of the board, the organization suggested directing questions to the bodies responsible for appointing them — the federal and provincial governments.

On the provincial front, Premier Stephen McNeil recently attended a major oil and gas conference in Houston where he argued that offshore oil and gas exploration should be permitted in restricted marine protected areas according to reporting by the CBC.

Conflicting responsibilities?

Currently, the CNSOPB is responsible for the regulation and development of Nova Scotia's offshore petroleum resources.

Fitzgerald believes the responsibilities need to be separated so that an independent body would be in charge of making sure Canada's waters are kept safe.

CNSOPB stressed that their job is to ensure regulatory compliance.

"Everything we do is guided by federal and provincial law through the Canada-Nova Scotia Offshore Petroleum Resources Accord Implementation Acts and the associated regulations. Before we grant an authorization, our experts go to great lengths to ensure that the proposed work will be completed in a safe, secure and accountable manner," said O'Rourke.

The problem of conflicting responsibilities will only increase with the introduction of Bill C-69 says the Sierra Club's Fitzgerald. That bill, sponsored by Minister McKenna, is currently in session and gives more power to the CNSOPB in terms of impact assessments.

Fitzgerald argues that Canada hasn't learned the lessons of the past and worries we may have condemned ourselves to a repeat of BP's Deepwater Horizon disaster, should an offshore well blow out.

“The fact that BP was approved in spite of pretty intense concern that’s been raised — it’s pretty shocking," she said. "And it gives very little credibility to any moves to protect the ocean on behalf of the government right now.”

“At the heart of it, it speaks to the influence of the oil industry on our leaders.”