Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Standing on a boat off the west coast of Haida Gwaii in June of 2013, marine mammal researcher John Ford was looking at something he thought he’d never see in his lifetime.

“It was total shock,” he said.

A rare North Pacific right whale was jumping and breaching, swimming around with a pod of humpback whales.

It was confirmation. Earlier that week, one of his colleagues had spotted the whale.

Ford had been researching whales for the previous four decades and headed the cetacean research program at the Pacific Biological Station in Nanaimo, B.C.

These were the first recorded sightings of the species in Canadian waters since 1951, when the effects of more than a century of over whaling had reduced their population to dangerously low levels.

A few months after the sightings by Ford and his colleague, a second and different whale was seen off the coast of Vancouver Island.

Now, five years later and in almost the exact position as the first sighting, a third, much younger, North Pacific right whale was photographed in early June.

“For those of us whose careers, whose life work has been working on whales off our Coast, we’d kind of given up hope that these animals would ever be seen again here,” said Ford, who has since retired, yet is still active in the research. “It’s very thrilling.”

Although no exact number exists due to a lack of data and sightings, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans estimates fewer than 50 of these whales exist today.

The sighting this month was made by crew on the CCGS Vector, a Canadian Coast Guard Vessel that was conducting a shellfish survey west of Haida Gwaii. Suspecting they had just witnessed something rare, the crew sent the photos off to the Pacific Biological Station, where they eventually ended up in front of Ford and his colleagues.

Ford was able to confirm that it was indeed the third recorded sighting, including the two in 2013, of the rare species of whale that experts believed had been nearly extirpated.

Hunted to near extinction

Its name says it all. The North Pacific right whale was considered the ‘right’ whale to hunt thanks to its large size (up to 17 metres, longer than the average bus), slow movement and tendency to float when killed.

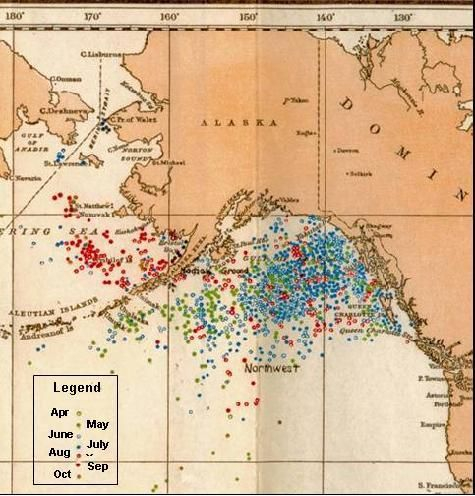

A study in the Journal of Cetacean Research and Management says between 26,500 and 37,000 right whales were killed in the North Pacific, the Bering Sea and the Sea of Okhotsk between 1839 and 1909. Fishing was so aggressive that 80 percent were killed in one decade alone, 1840-49.

By the time the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling was signed in 1946 in order to conserve whale stocks, the species had been almost entirely eradicated from Canada’s waters.

Further illegal Soviet hunting continued through to 1979 and slowed any recovery of the North Pacific right whale population.

Cause for Hope

Part of the DFO, researchers at the cetacean research program conduct scientific studies on whales, dolphins and porpoises off Canada's west coast. Their work assesses the conservation status of many endangered species.

Ford’s successor as head of the program is Thomas Doniol-Valcroze, who is equally excited by the latest sighting.

“It's hard to derive any solid conclusion from a single sighting, but, certainly, there seems to be a trend in recent years,” Doniol-Valcroze told National Observer. “It could be the beginning of a trend where we see these whales more and more.”

Doniol-Valcroze hopes new research can determine whether the population is actually growing or just becoming more visible.

The recent sighting has set the wheels in motion for more research on the North Pacific right whale.

Doniol-Valcroze said his team will anchor underwater acoustic recorders to the sea floor in such key areas as west of Haida Gwaii. The group of islands, formerly known as Queen Charlotte Islands, sits about 50 kilometres off the northern Pacific coast of British Columbia.

The devices, which can record up to 60 kilometres wide, will record the calls of whales as they swim by. After a year, the team will remove the underwater recorders and review the information.

The hydrophones will allow the researchers to study the areas as if they were on site 24/7 and will help them determine whether these sightings were more than just a fluke.

“It [the recorded data] could help us make dedicated surveys or cruises to go find them and take photos or skin samples for genetic analysis,” said Doniol-Valcroze, who has been studying whales for more than 20 years. “It could also help us understand if there's any potential for conflict with human activity, such as fisheries or if we should protect the areas.”

Local communities have raised concerns about threats to whales lower down the coast.

Last week in Vancouver, Transportation Minister Marc Garneau announced $167.4 million for actions to protect and support the recovery of the Southern Resident Killer Whale, the North Atlantic right whale, and the St. Lawrence Estuary beluga whale.

The initiative is designed to address their main threats - lack of prey and disturbance from vessels, including noise and pollution from land-based sources.

The Southern Resident Killer Whale in the Salish Sea face an imminent threat to survival and recovery which requires immediate attention, the announcement said.

“Whales play a very important role in our marine ecosystems, and these iconic species also hold immense cultural value,” said Garneau. “We have a responsibility to continue to take action to protect our whale populations.”

As for the North Pacific right whale, Ford and Doniol-Valcroze stressed that it’s too early to know the exact significance of the rare sightings, but they admit that even catching a glimpse gives cause for hope that these underwater giants will once again fill these waters.

Comments

These recorded sightings are exciting for me so I can hardly imagine what John Ford, a professional who has dedicated his career to cetacean ecological research, has and is feeling.

Good on you guys for this work and may we as citizens of this great country work to support you this on-going generational research by staying on top of any future governance who would abandon this necessary science in the realm of maintaining and enhancing the biodiversity of this Planet and its "grand dance of life", something into which we have recently evolved an understanding.