Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

A prominent government scientist says he felt compelled to "back down a bit" from advice about improving pollution monitoring by Environment and Climate Change Canada after getting some pushback over his proposal's modest $60,000 price tag.

David Tarasick — an atmospheric scientist who became a poster boy of government muzzling when Stephen Harper was prime minister — said his higher-ups challenged him about the importance of monitoring of ozone during an internal review, after he and his colleagues finished a draft copy of a new scientific assessment.

The revelation has led one science advocacy group to question the Trudeau government's commitment to atmospheric monitoring in Canada.

“It’s definitely concerning to me that it seems like this government is not prioritizing monitoring around ozone, climate and atmospheric sciences,” said Katie Gibbs, executive director of Evidence for Democracy, an Ottawa-based group that advocates for evidence-based decision-making.

'Find the money somewhere else'

In 2011, the Harper government suspended operations at two stations that launch a specialized pollution-detecting probe called an ozonesonde, one near Toronto and the other near Regina.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, while in opposition, railed against the closures of these stations in Egbert, Ont. and Bratt’s Lake, Sask.

Four years later, Tarasick and his colleagues wrote in a scientific assessment, obtained last year by National Observer, that recommended at least one of these stations, Egbert, needed to resume regular monitoring to achieve federal scientific objectives.

The government said last year it was considering its options. Meanwhile, Tarasick and his colleagues had been drawing up a new assessment of the monitoring network, and were receiving feedback from a range of public servants.

In an interview, Tarasick explained how he had drafted a proposal, prompting a manager to tell him that re-starting regular launches at Egbert would be so expensive that it would force the department — which recently told Parliament that it had about 6,000 full-time employees and was planning to spend about $1.5 billion in 2018-2019 — to make cuts elsewhere.

“The draft was passed around through other branches…on the issue of Egbert specifically, my current manager — very sharp guy — challenged me," Tarasick told National Observer. "He said, ‘That’s going to cost a lot of money. And you know that money is going to come from other programs.’”

The pushback was enough that Tarasick said he “backed down a bit” from a more direct recommendation he and his colleagues had made in 2015, when they explicitly called for renewed monitoring from Egbert.

The latest scientific assessment by scientists Tarasick, Vitali Fioletov and Chris McLinden in the department’s air quality research division, dated Jan. 9, 2018, drops the unequivocal language about restarting Egbert.

Instead it says to “continue ozonesonde launches at the current eight sites," adding it will be “beneficial” for Canada to carry out more launches on a "periodic" basis at Egbert. “I’d backed down a bit on Egbert,” said Tarasick.

But he insisted that the debate that happened in the department was “exactly what should have happened” — in other words, a careful scrutiny of taxpayer dollars. “Several managers got involved, quite a number of other scientists were asked for their opinion,” he said of the draft report.

Tarasick said his manager assured him “he would find the money” for the periodic launches instead. He said Egbert was costing $60,000 a year to do regular launches, or about $1,000 per launch.

Atmospheric chemists in particular, he added, were worried that if the department stuck the $60,000 into ozonesondes, funding wouldn’t be available for other pollution measurements.

“If you want to advocate that we should have more money, well, then you’d get all the scientists on your side. We’re always trying to do the best we can with the money we have," he said.

Department says it's following scientific assessment

The Environment Department says it has no plans to re-open Egbert, and is instead implementing the recommendations from the internal review, which says to continue monitoring at the eight stations.

“In the near term...there is no plan to resume ozonesonde launches from these locations or to create new ozonesonde stations for long-term monitoring,” departmental spokeswoman Christelle Chartrand said.

Asked why the department did not have enough funding available for its atmospheric scientists to cover a $60,000 project, another departmental spokeswoman, Samantha Bayard, noted the assessment underwent “an internal scientific peer review" which guided its next steps.

“Recommendations from the review are being implemented, including continuing with weekly launches of ozonesondes at eight sites across Canada, including coverage in the Arctic, for on-going long-term monitoring of tropospheric and stratospheric ozone,” said Bayard.

Bayard also noted the federal government’s air quality standard for ozone is "under review."

“Protecting the health and safety of Canadians is a top priority for the Government of Canada. That’s why the Government of Canada is committed to securing clean air for communities by limiting and reducing air pollution from industry, transportation and other sources,” she wrote.

Gibbs, however, said the decision not to re-fund ozone stations cut during the Harper years was concerning when seen as part of a pattern of funding cuts to government science.

The Trudeau government rolled out more than $3 billion over five years for scientific research at university labs and elsewhere during its 2018 federal budget. Gibbs noted it didn’t renew funding for a key program, the Climate Change and Atmospheric Research (CCAR) program, that funded several projects.

One of those, the Polar Environment Atmospheric Research Laboratory (PEARL) — arguably the most important Arctic research lab in the world — received last-minute emergency funding to stay operating. But the money is only temporary, through September 2019.

Gibbs said the government has seemed to focus on education, adaptation and mitigation of climate change, “but it seems like in that re-prioritization they’ve forgotten that you still have to do the monitoring of things like ozone and climate, and our atmosphere.”

The recent discovery that the ozone layer is being damaged again by banned chemicals serves to demonstrate the importance of monitoring, she said.

“We had one of the biggest environmental successes — the Montreal Protocol — everyone agreed to stop using (ozone-depleting substances). But they kept monitoring it, just in case, and sure enough, the scientists discovered that surprisingly, CFCs were starting to be on the increase again.”

The only continental site in eastern North America

Tropospheric ozone pollution is different from the ozone layer, which helps protect against harmful UV rays from the sun.

In contrast, tropospheric ozone is a big contributor to climate change, and is considered the third-most important greenhouse gas after carbon dioxide and methane. It is also a health hazard, as it can irritate or permanently damage people’s lungs, aggregate lung diseases and damage the immune system.

This kind of ozone pollution is created as a result of photochemical reactions when higher temperatures and sunshine combine forces with emissions of nitrogen oxides or volatile organic compounds that react with the sun’s UV rays. These emissions come from burning fossil fuels, as well as forest fires and lightning.

Air pollution causes thousands of premature deaths and illnesses in Canada and billions in economic losses every year, according to recent research.

Scientists are interested in measuring how much tropospheric ozone drifts from one part of the planet to another, both in the context of climate change and because imported ozone can raise background levels of pollution, putting pressure on air quality.

“Long-range transport of ozone from distant sources can be quite important...emissions in Asia may affect ozone pollution in Canada,” reads Tarasick's paper.

Canada has extensive monitoring networks for ozone, such as the National Air Pollution Surveillance Network (NAPS) of 224 ground stations, as well as the Canadian Air and Precipitation Monitoring Network (CAPMON) which lists more than a dozen stations measuring ozone as of 2017.

But Tarasick’s paper makes clear that observations from either NAPS or CAPMON aren’t sufficient enough to get at ozone pollution measurements in the so-called “free troposphere,” or the layer of the atmosphere where weather balloons can fly, just above the layer at ground level.

Satellites, airplanes and ground measurements all have drawbacks for this type of measurement, say scientists.

Ozone’s climate-changing strength depends strongly on the altitude where it gathers, but there is large amount of uncertainty in the scientific community about how much tropospheric ozone existed before the industrial revolution, and how it’s distributed today.

“Reducing this uncertainty is a focus of current research efforts internationally,” the paper states.

For this, scientists need to rely on the Canadian Ozonesonde Network, which can measure ozone pollution from ground level up to 36 kilometres of altitude.

“While originally developed for stratospheric monitoring, ozonesondes produce good measurements of tropospheric ozone making them the primary source, worldwide, of information on ozone amounts in the troposphere,” reads Tarasick’s paper.

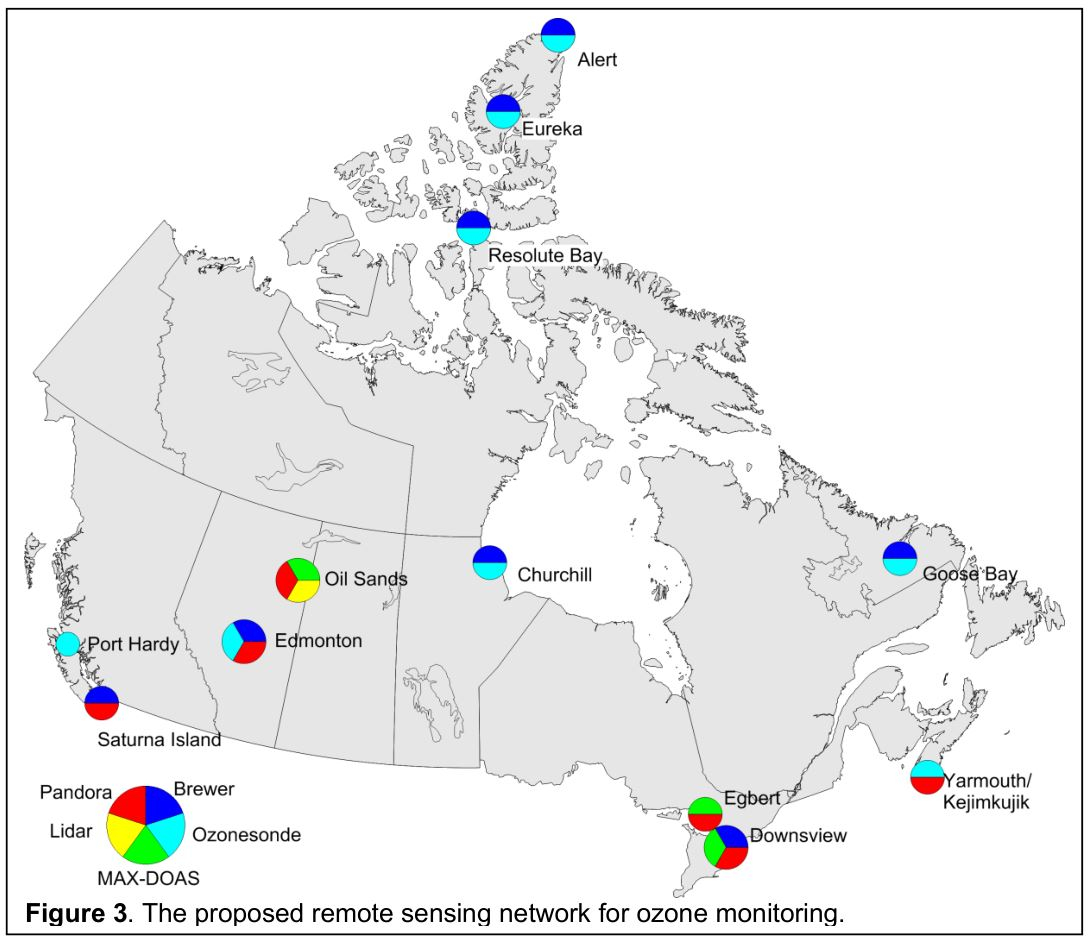

But the network is much less extensive than NAPS or CAPMON, with just eight sites — three above the Arctic circle, two at mid-latitudes and three more in the south.

“Egbert, Ontario is the only continental site in eastern North America, and is significantly affected by long-range transport from western Canada and boreal fire regions,” reads the paper.

“Its short record has been extensively used for satellite validation and pollution transport studies. It would be beneficial to retain and/or develop a capacity to support periodic ozonesonde launches at Egbert or other temporary locations as part of larger strategic network campaigns.”

West coast station re-opens a year after shutdown

Environment and Climate Change Canada also confirmed that the country has had no federal scientific research station regularly monitoring tropospheric ozone pollution on the west coast for a year, while a site was shut down and a replacement location scouted and set up.

ECCC closed its Kelowna, B.C. monitoring station on June 30, 2017. Between then and June 13 of this year, when a replacement station in Port Hardy, B.C. launched its first ozonesonde, the closest station to the west coast was in Edmonton.

“Back on the west coast!” tweeted Bernard Vigneault, executive director of the air quality research division, on June 14, commemorating the first ozonesonde launch from Port Hardy.

The department had said at the time that construction undertaken by the University of British Columbia’s Okanagan campus in Kelowna, which was hosting the station, made the spot “permanently unsuitable.” The university, however, said it tried to accommodate the scientists’ needs.

The department said Dec. 5, 2017 that that it was still picking between two possible alternatives. Asked again about the status two weeks later, the department revealed that it had picked the new site in Port Hardy.

Comments

Pushback on pollution monitoring of $60,000 but $30,000 to change one word in a title, no problem??