Kinder Morgan privately eyes Trans Mountain opponents

On a sunny Friday morning in late May, protesters trickled in one by one to mingle at the Watch House campground, not far from the gates to Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain Westridge Marine Terminal in Burnaby, just east of Vancouver. So did two men hired by Kinder Morgan to report back on their activities.

An investigation by Morgan Sharp and Dylan Sunshine Waisman

Warren Forsythe and his employee, Terry Shendruk, were meticulous.

Forsythe got a coffee from a nearby Tim Hortons at around 6:15 a.m. on May 25, in the midst of weeks of protests against the company's planned pipeline expansion, before receiving briefing materials from a man named Randy Harcourt.

He and Shendruk then returned to the site near the Watch House, a centre of operations for the protest movement against the pipeline project that is located mere metres from Kinder Morgan’s property line.

The project's detractors erected the Watch House on March 10 on the traditional territory of the Tsleil-Waututh and Squamish Nations to keep an eye on the construction.

Forsythe and Shendruk initially observed from a distance before noting their approach was being videotaped by a protester, according to hand-written notes attached to an affidavit, signed in Kamloops and submitted to the B.C. Supreme Court on May 30. That evidence was used to support the company's bid to have tougher terms imposed on the protesters, who had been disrupting operations for months.

The expanded Trans Mountain facilities would triple the capacity of an existing pipeline system to ship up to 890,000 barrels per day of heavy oil and other petroleum products from Alberta to the west coast through a slightly modified route. Supporters of the pipeline, including the federal and Alberta governments, say it would drive growth and support a transition that enables action on climate change. Opponents say the project could lead to spills and push Canada's climate change goals out of reach.

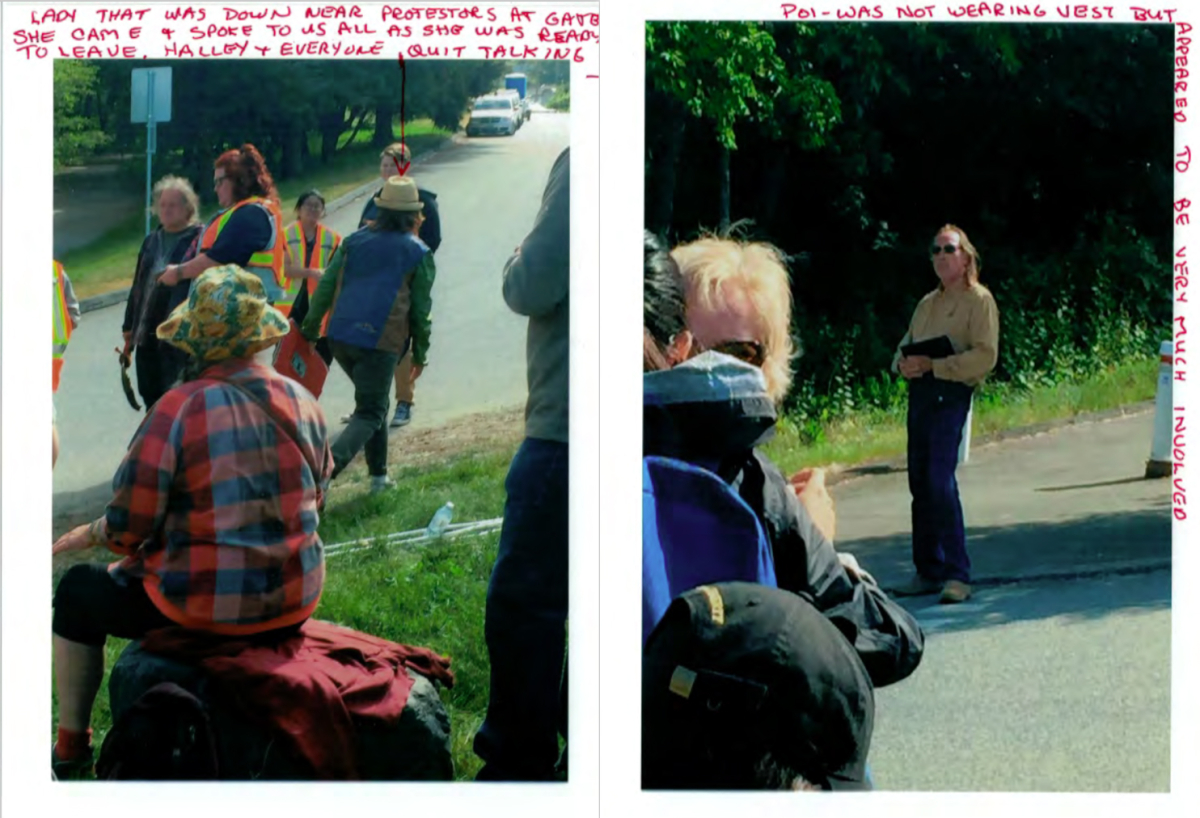

Forsythe chatted with some of the other people who had shown up that day, and took particular care to identify the group’s leaders, who were wearing high-visibility vests. Throughout the day he took photographs of numerous people on site, which he later annotated.

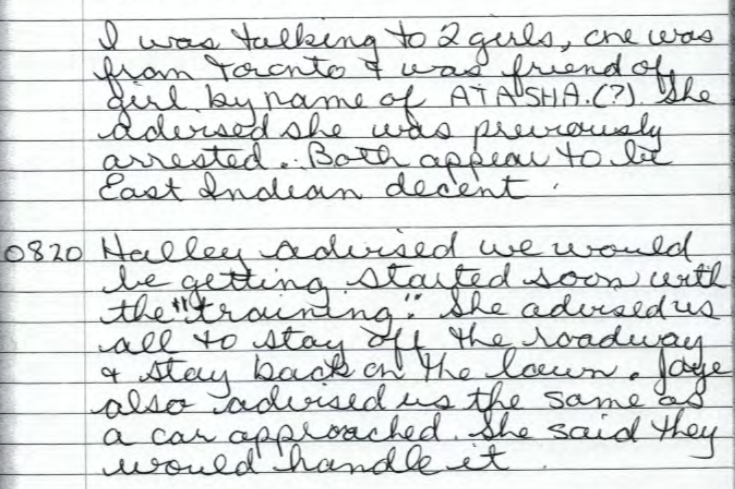

"I was talking to 2 girls, one was from Toronto & was friend of girl by name of ATASHA (?) She advised she was previously arrested. Both appear to be East Indian decent (sic.)," said one section of the notes taken by Forsythe. "(An organizer) advised we would be getting started soon with the 'training.'"

Forsythe and Shendruk are private investigators. The information they collected was used to convince B.C. Supreme Court Justice Kenneth Affleck that protesters were “making every effort to calculate and orchestrate” their protest to maximize disruption of Kinder Morgan’s construction activities. Affleck tightened the terms of an earlier injunction, removing a 10-minute grace period between when police would read a warning for those blocking access to disperse and when arrests would be made.

The earlier injunction created a five-metre exclusion zone around Kinder Morgan's Burnaby Mountain tank farm and Westridge Marine Terminal. The injunction can now also be applied to Kinder Morgan operations anywhere in the province.

The two affidavits included Forsythe's 23 pages of notes and Shendruk's five pages about the protesters' operations as well as 30 surreptiously-snapped photographs. They shined some light on the little-understood but growing role of private investigators in Canada’s policing of protest.

“The fascinating thing is that we know very little, certainly in Canada, about the role of private eyes and private investigators and even the security branches of the energy companies in terms of their role in collecting intelligence and surveillance information on protesters,” said Jeffrey Monaghan. He is an associate professor at Carleton University's Institute for Criminology and Criminal Justice who co-authored the book Policing Indigenous Movements, published in May.

Monaghan and co-author Andrew Crosby made extensive use of access to information legislation to illustrate how the federal government and its law enforcement and security services have coordinated with resource companies to deal with opposition to Enbridge’s failed Northern Gateway project, the Idle No More movement and two other Indigenous-led protest movements.

“What we do know is that over the past few years the federal government has made a fairly substantive effort to try to integrate these private companies, especially the resource companies and their security wings, into the national security bureaucracy,” he added in a telephone interview.

This includes an RCMP web portal specifically for companies who operate what the government considers critical infrastructure (including pipelines) to upload information about protests as part of a ‘suspicious incidents reporting’ framework.

Private investigators have much more leeway in how they go about obtaining information and much less oversight of their activities than law enforcement.

“We need to know more about what’s happening in terms of the use of private intelligence and where that data is going,” Monaghan said. “The big question is what happens with all this information.”

“A lot of this information is sitting in data banks and can be revisited at later points. We don’t know what the filters and the thresholds are for keeping this information.”

The sharing of such information among different government agencies became easier when the anti-terror Bill C-51 was passed under the previous Harper government.

Formerly RCMP, today private investigators

People participate in a protest on March 27, 2018. Those wearing fluorescent safety vests were deemed of interest by the investigators. Photo by Rogue Collective/Protect the Inlet

According to his LinkedIn profile, Warren Forsythe is the founder and owner of Forsythe Security Consultants, which claims niche expertise in the oil and gas and mineral exploration industries, with experience “interfacing with a wide range of stakeholders including activists.”

He served with the RCMP for 28 years in the major crimes, drugs, and emergency response units, “and had a great time doing it all,” his profile said. After retiring from the force he franchised several McDonalds restaurants, before settling into his current work as a security consultant, “just so I wouldn’t get too bored in retirement,” his profile said.

He declined to comment when contacted by National Observer, referring queries to Kinder Morgan media relations staff, who did not reply to repeated requests for comment.

Terry Shendruk had a nearly 33-year career with the RCMP, according to his affidavit, at one point serving as B.C.’s only livestock investigator, dealing with everything from stolen cattle to fencing disputes, according to media reports. He could not be reached for comment.

About half an hour after arriving on site that day, Forsythe and Shendruk gathered around a woman wearing a fluorescent orange and yellow vest with reflective sections who provided some basic information on how the protest would proceed. This included identifying those who only wanted to be supporters on the sidelines, those who planned to blockade the site but leave before 10 minutes elapsed, and those who chose to get arrested.

"She explained that before May 8 it was a 500 fine + 25 hrs community work but now its 5000 fine + 250 hours," Forsythe wrote. "She said that even after court you don't get a criminal record so you can travel to US."

He added, "She went on to explain that if you planned on being arrested or having the injunction read you need ID with you. If not she said the police would escort you away."

She also listed three rules, he said. No weapons of any kind, no drugs or alcohol, and no cellphones unless locked with a password.

"No fingerprint or facial ID as police can't make you enter your password but they can hold up your finger to it or put it up to your face," he wrote.

When the organizer went around to collect contact details in case of arrest, Forsythe gave a false email address and phone number and worried this would backfire.

"I saw her approaching Terry so I went over and said to Terry I'll give her mine. So I gave her [email protected] ph 778-xxx-2252. Neither correct," he wrote.

“I had to keep an eye on her and others to see if that burnt me or not and it didn’t appear to,” he added.

When people who had gathered were getting introduced and asked to share reasons for coming, Shendruk provided a cover story that portrayed Forsythe as his driver, the court documents show. Forsythe reiterated the story and said his reasons were similar to a woman who later that day sat in a chair in front of Kinder Morgan's gates and had the terms of the injunction read to her by police. When the woman returned to the larger group after blocking the gate he sidled up to her to ask more questions.

"I ask her if she was nervous, she said at first but just thought about how she was doing her part to save the animals and environment and she relaxed," Forsythe wrote.

His notes said she told him that an organizer kept track of time and told her when to leave.

His questioning appeared to be an attempt to establish that organizers were intentionally getting protesters to block the road for as long as possible, a point on which the judge ultimately agreed.

The cost of protest

Led by Indigenous activists' drums, a first line of protesters claim places in front of the gate and a “Stop Kinder Morgan” banner is raised and strapped to the main gate, blocking the view of green tanks and forklifts behind the chain link fence. Photo courtesy of Protect the Inlet

On a typical day on the front lines of the protest, a group of people led by Indigenous activists drum and sing protest anthems and local Tsleil-Waututh songs during a 10-minute procession along a well-worn rainforest trail, past the cedar Watch House and up to the Kinder Morgan tank farm on Burnaby Mountain.

Once there, a first line of protesters claim places in front of the gate. A “Stop Kinder Morgan” banner is raised and strapped to the main gate, blocking the view of green tanks and forklifts behind the chain link fence.

The first group often waits with a large group of supporters on the sidelines, non-uniformed police ever-present in grey t-shirts and hats, and a line of semi-trailer trucks piling up behind them. It is often several hours before Kinder Morgan makes the call that the injunction has been breached and asks the RCMP to make arrests

Uniformed police then march towards protesters in a group of ten, wearing bright fluorescent yellow uniforms and large black hats. They hand copies of the injunction to each blockader and read the 10-page document aloud. It's a process that can take 15 minutes.

Protesters get a 10-minute grace period before police return, after which some agree to leave the picket line without repercussion. Others stay put and get arrested, either walking or forcibly moved to a nearby processing tent.

Since the injunction's terms have been tightened police can now read the text via loudspeaker and are free to begin the arrest process almost straight away.

At this point, a second wave of protesters comes in, and the process begins anew. This could happen three or four times a day, significantly slowing construction.

Last year, Kinder Morgan Canada CEO Ian Anderson said that delays with its Trans Mountain expansion project were costing the company $90 million per month.

Private investigators mingled with protesters on various dates

Protesters face an RCMP agents line at a protest in Burnaby, British-Columbia, on March 23rd, 2018. Image courtesy of Rogue Collective/Protect the Inlet

While the evidence submitted to court only covered one day of protests, Kinder Morgan counsel Maureen Killoran told the court the “two gentlemen mingled among the protesters on various dates.”

Kinder Morgan did not respond to questions about the undercover operation, including when the company first made use of private investigators in British Columbia or elsewhere in Canada and whether the pair are the only private investigators the company has engaged.

The RCMP, when asked if they are kept informed of when private investigators are active at protests or if there is any coordination between law enforcement and private actors, said that “the Royal Canadian Mounted Police does not comment on operational matters, including investigations and investigative techniques that may or may not be used by the police and other organizations.”

“The primary goal of the RCMP is to ensure that protests in support of, or opposed to, the Kinder Morgan pipeline expansion project are peaceful, lawful and safe,” an emailed statement said.

When asked about possible coordination with private investigators by Canada's main spy agency, John Townsend, the head of public affairs at the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS), said its mandate is "to identify and advise the government of threats to our national security" as defined in the CSIS Act, which specifically excludes lawful protest and dissent.

He said CSIS does not disclose investigational interest or practices when asked a follow-up query about the lawfulness of protest actions or whether they are considered detrimental to the interests of Canada. He did not explicitly state that CSIS is not investigating protesters opposing Trans Mountain.

No obligation to reveal identity

Anna Gerrard was arrested by the RCMP at a "die-in" protest on May 16th, 2018, and refused to go with RCMP agents to the processing tent. File photo by Dylan Sunshine Waisman

In British Columbia, private investigators must be licensed by the office of the solicitor general to collect information about “crimes, offences, contraventions or misconduct, or allegations of crimes, offences, contraventions or misconduct” as well as a person's whereabouts, the location and recovery of stolen property, and the cause of damage to property or injury to a person. They are not allowed to wear a uniform.

“For the most part, we are under no obligation to reveal who we are,” Dale Jackaman, the president of the Private Investigators Association of British Columbia, said in an emailed response to queries. “Circumstances can arise where common sense, ethical issues, etc, will dictate a response. As a rule, we do not state who our clients are as that would be a breach of privacy and confidentiality."

Private investigators in British Columbia are typically paid between $60 and $120 an hour for corporate work, according to two industry participants who declined to be identified.

“Professional investigators have many roles to play in society, but a key one relates to the collection of evidence in both civil and criminal matters. That work is extensive and equates to tens of millions of dollars in the province of B.C.,” Jackaman said.

Protesters said it was vexing but not surprising that the company was making using of informants.

“Part of civil disobedience is knowing that you are breaking the law, that is always going to be evidenced at some point,” said Sarah Beuhler, a member of the Protect The Inlet group of Indigenous and allied activists that sprang up with the construction of the Watch House.

“When somebody chooses to go through that process as a plant or a spy I don’t think there’s anything illegal about it … they are just doing a job in a system that demands fairly dehumanizing things from its employees,” she added.

Keith Stewart, a senior energy strategist at Greenpeace, also acknowledged his group sometimes engages in illegal activities in order to make their point, including several protesters who last week suspended themselves from the Ironworkers Memorial Bridge across the Burrard Inlet for almost 40 hours to block an oil tanker leaving Kinder Morgan’s Burnaby terminal.

“Engaging in public protest is part of the democratic process,” he said. “No significant major social change has come about in the last century without it involving civil disobedience."

One of those arrested and charged with mischief at the bridge was Greenpeace’s Mike Hudema, who was also heavily featured - mistakenly it turns out - in Shendruk's account of the May 25 protest. Hudema, a common presence at Protect the Inlet protests, said he is troubled by the private eyes spying on him and others in civil society groups.

"As we were approaching 11:00 am I first noted a gentleman who I felt was Mike Hudema arrived and sat on the grass at the far end of the gathering," Shendruk wrote. "He was wearing a red long sleeve shirt and a black vest."

"I don't think I've worn a vest since grade six prom," Hudema said, insisting he was not on site on that day.

“It’s pretty concerning anytime anyone pretends to be somebody else with the explicit purpose of gaining more information about you," he said. "It’s very disingenuous, it’s extremely problematic.

"Not only is the intention to get personal information about people, but it's to potentially intimidate them directly and then also intimidate others from joining in," Hudema said. "All of those are really problematic. If people are peacefully expressing their dissent, that should be something that is encouraged in our society, not something that we are trying to chill people away from."

It was not immediately clear whether the apparent mistake in Shendruk's notes would have an impact for ongoing enforcement of the injunction.

In 2014, a judge vacated civil contempt charges against more than 100 Kinder Morgan protesters due to GPS errors in a previous injunction.

"Had we known that at the time we could have demanded that the former officers attend court and be cross-examined on their affidavits," said Martin Peters, a lawyer representing several protesters including one of those named in the original affidavit. "Something like that — that would go fundamentally to the credibility and accuracy and reliability of the affidavit — could have been dynamite."

Protests have dogged Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project since 2014, two years before it was given federal government approval with 157 conditions attached. Some 100 people were arrested during a protest in November 2014 that blocked crews from conducting drilling and survey work. There have been frequent blockades since November 2017, a month after Kinder Morgan was granted the right to proceed with construction.

In March 2018, Kinder Morgan won an injunction to keep protesters from physically obstructing the Westridge Marine Terminal and nearby Burnaby Terminal, as well as any other Trans Mountain-related site. The next day, 5,000 people marched up Burnaby Mountain to protest the project while Indigenous leaders built the Kwekwecnewtxw, or traditional Watch House, in under 16 hours.

Since then, more than 200 people have been arrested for breaking the injunction, among them federal Green Party leader and MP Elizabeth May and Kennedy Stewart, a New Democratic Party MP who is stepping down to run in Vancouver's upcoming mayoral race. The courts agreed with crown prosecutors and increased penalties as protesters continue to hinder construction of the pipeline and related terminal expansions.

The project would increase the number of oil tanker shipments by nearly seven times through Burrard Inlet, potentially disrupting a threatened population of Southern Resident Killer Whales, which only number about 75, in the Salish Sea.

On May 29, Kinder Morgan announced an agreement to sell the company's existing pipeline and expansion assets to the federal government for $4.5 billion. It would cost at least another $7.5 billion to complete the project.

Federal officials won't say who will pay for spies

The federal government has declined to say whether they are financing the use of private investigators by Kinder Morgan. The Natural Resources Minister Jim Carr is seen here getting to an emergency cabinet meeting in Ottawa on April 10, 2018. File photo by Alex Tétreault

An official with the federal Finance Department declined to say whether the government was paying for any use of private investigators by Kinder Morgan since Ottawa agreed to buy the project. As part of that agreement Kinder Morgan is continuing construction this summer at taxpayer expense, with the deal expected to close by September.

Given the sale to government, Greenpeace’s Stewart said the government has two conflicting roles to play.

“It’s an odd dynamic and it puts the government in a conflict of interest, where they have a private interest in the success of the pipeline and yet they are also supposed to be playing the role of referee,” he said. “They are both referee and one of the teams.”

His colleague Hudema added that he didn't expect the tactics to change much with the change of ownership.

"We haven’t received any firm commitment from the federal government that they will not engage in these type of tactics,” he said, noting that a government minister had previously mused about using the military to protect construction workers on the project, before backtracking.

In 2016, Natural Resources Minister Jim Carr commented on the possible use of "defence forces" or police during future protests over pipeline projects that are not peaceful but he later apologized to Indigenous leaders and has frequently said since then that he misspoke at the time.

“They still haven’t said categorically it’s not a tactic they will use,” Hudema said.

On July 3, Kinder Morgan filed an updated summary of its construction outlook for the next six months with the National Energy Board, with work in Alberta expected to begin in August and in the North Thompson region of British Columbia in late September.