Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

A proportional voting system favours voters. It ensures that just about every vote counts for something: support for a particular party, a representative, or both. If you're not sure which voting system you support, take this referendum guide survey and see which one reflects your values.

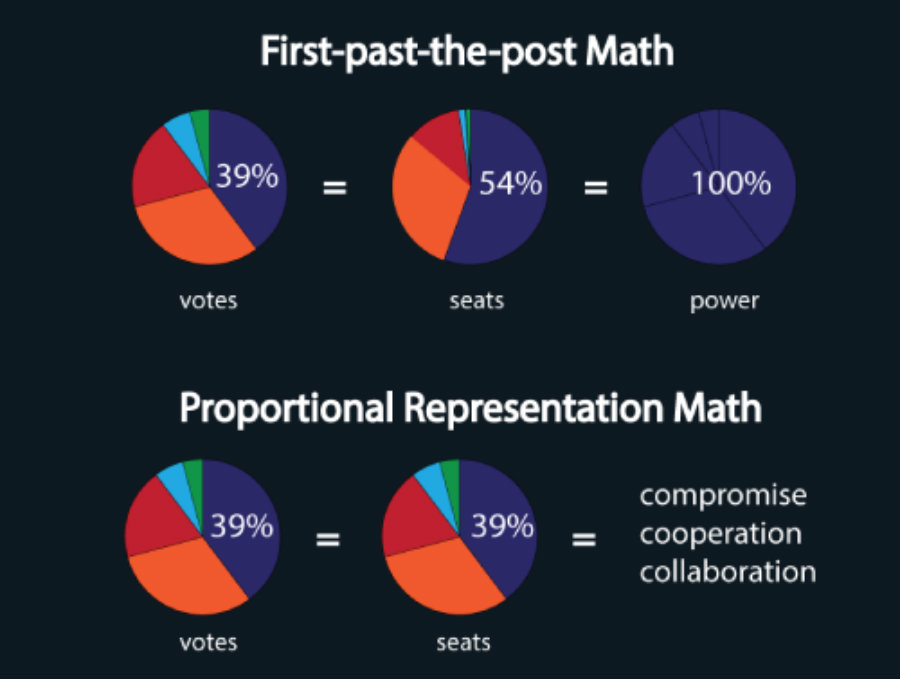

Proportional representation (ProRep) systems almost always produce cooperative majority governments, which in turn create more consistent policies that don't swing wildly between successive governments.

ProRep systems result in higher voter turnouts and less voter cynicism. They encourage open debate about new ideas and old approaches instead of burying them or forcing confrontation in the streets or costly court challenges. Ontario Premier Doug Ford’s bull-in-a-china-shop government already faces a number of legal actions against rash enactments, all at taxpayers’ expense.)

But there's a reason why some people fight fiercely against the proportional system. It doesn't favour them. Or rather, they shift accountability back onto the shoulders of politicians. They compel politicians to cooperate, work together, and work out their differences, rather than shouting irrelevant nonsense back and forth across the aisle of the provincial legislature, or trashing their political rivals’ policies once they gain power themselves. ProRep systems are used in countries like Denmark, Norway, and New Zealand, and are already used by 89 countries around the world.

So it’s not surprising that a smattering of B.C.’s old guard politicians – like NDP stalwart Ujjal Dosanjh – are coming out of the woodwork to resist a move to proportional representation, and cling to the horse-race world of the current “first past the post” system.

It’s not surprising that a number of well-heeled businesspeople don't want it – like millionaire Jim Shepard, who paid for anti-ProRep ads in B.C. newspapers. They know that a typical majority coalition government in a proportional system is much harder to manipulate than a more vulnerable minority first-past-the-post regime.

Long-time NDP stalwart Bill Tieleman has also expressed fear about proportional voting systems for years, alleging without foundation that it allows extremists to take over the government. He ignores the fact that all the proposed ProRep systems offered in the referendum compel small parties to earn at least five per cent of the total vote in order to get top-up votes; this means getting just about 100,000 voters onside — or 172,000, if all registered voters cast their ballots.

But why all this fear and loathing? Why do many older political figures, who cut their teeth in the divisive, polarized world of first-past-the-post electioneering, find the more collaborative process engendered by proportional representation so hard to swallow?

I believe it’s because they all know that giving up old-style politics, which worked so well for them, will cause them to lose dominance on the political scene. They know – and resent the fact – that proportional systems mean genuinely sharing power.

These proportional representation critics are (mostly) men, bred into a system where majority governments are rarely necessary to have complete political power, where candidates selected by party insiders can be parachuted into “safe” ridings in order to get elected, and where the illusion of representation can be preserved by plunking MLA offices down in local communities.

Walking into the office of an MLA who belongs to a different party from the one you support, and expecting to have a differing approach taken seriously, is as close to a fool’s errand as most of us ever come. You tend to meet a polite blank wall.

Have you had this experience? I certainly have.

The antagonism of previous governments to proportional representation, while understandable at one level, is shamelessly self-centred. The BC Liberal Party ruled the province for a decade and a half with successive minority voter support, and during that time, got away with rejecting every single bill presented by any opposition MLA – Green, NDP, or Independent.

Such unfettered power would certainly turn the head of any aspiring megalomaniac.

But this sort of political hyper-partisanship – and the concomitant rejection of majority voter opinion in the province – makes a shameful mockery of so-called democracy.

No better example of how the current system shapes politicians' behaviour can be found than in a speech made by the former B.C. Liberal Premier Christy Clark, not when she was in political office, but when she was a radio host between her two political stints.

From 1996 to 2004, and again from 2011 to 2017, Clark was an MLA, serving as a minister and head of government. But from 2005 till 2011, Clark worked as a talk show host at CKNW in Vancouver, and she was there when the first referendum was held on a proportional electoral system (single transferrable vote) in 2005.

Because so many callers expressed their distaste towards the first-past-the-post system, she abandoned her previous implicit support of that approach, and delivered a ringing and heartfelt endorsement of the proportional system proposed by a Citizens Assembly in May, 2005, and voted on in a referendum in that same year. Her speech remains one of the most eloquent affirmations of the virtues of ProRep in the province's history.

During her terms in office, however, Ms. Clark made no mention of electoral reform, and artfully employed all the dysfunctional qualities of the first-past-the-post system on a regular basis.

We live in a century where the most large-scale transformation of our conduct as a species lies before us. Global climate change, huge population numbers, rampant pollution, gross social and economic inequality, and massive impending shifts in the workplace brought about by technological change are all issues that need to be wrestled to the ground, if we are to achieve a secure and satisfying world for future generations.

We cannot afford, in these challenging times, to waste time swinging this way and that in our political affairs, pushed by contending political leaders. The "winner-take-all method" of the past won't work for 21st century challenges; for climate and many other issues, we need all hands on deck. Together. We need our leaders to work with one another to deal with the problems that beset us, not waste time shifting between right and left, or us versus them.

Consequently, we need a political system that encourages our leaders to share some of their power. Instead of simply fighting and criticizing one another all the time, we need them to do the hard work of governance through collaborative decision-making and consensus-based policies.

British Columbia – and the world – needs a much better system.

When you receive you package in the mail from Elections BC, I urge you to vote “Yes” to proportional representation.

Comments