Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

When Jeff Ward was younger, his parents hoped he might become a doctor. But when the Internet exploded in the 90s, the Métis and Ojibwe dreamer quickly taught himself to make websites instead of memorize symptoms. He learned he could get paid for his web work, and by the end of high school Ward was running his own business. His parents, both licensed nurses at the time, tossed aside their medical dreams for their son, understanding he had been bitten by the technology bug.

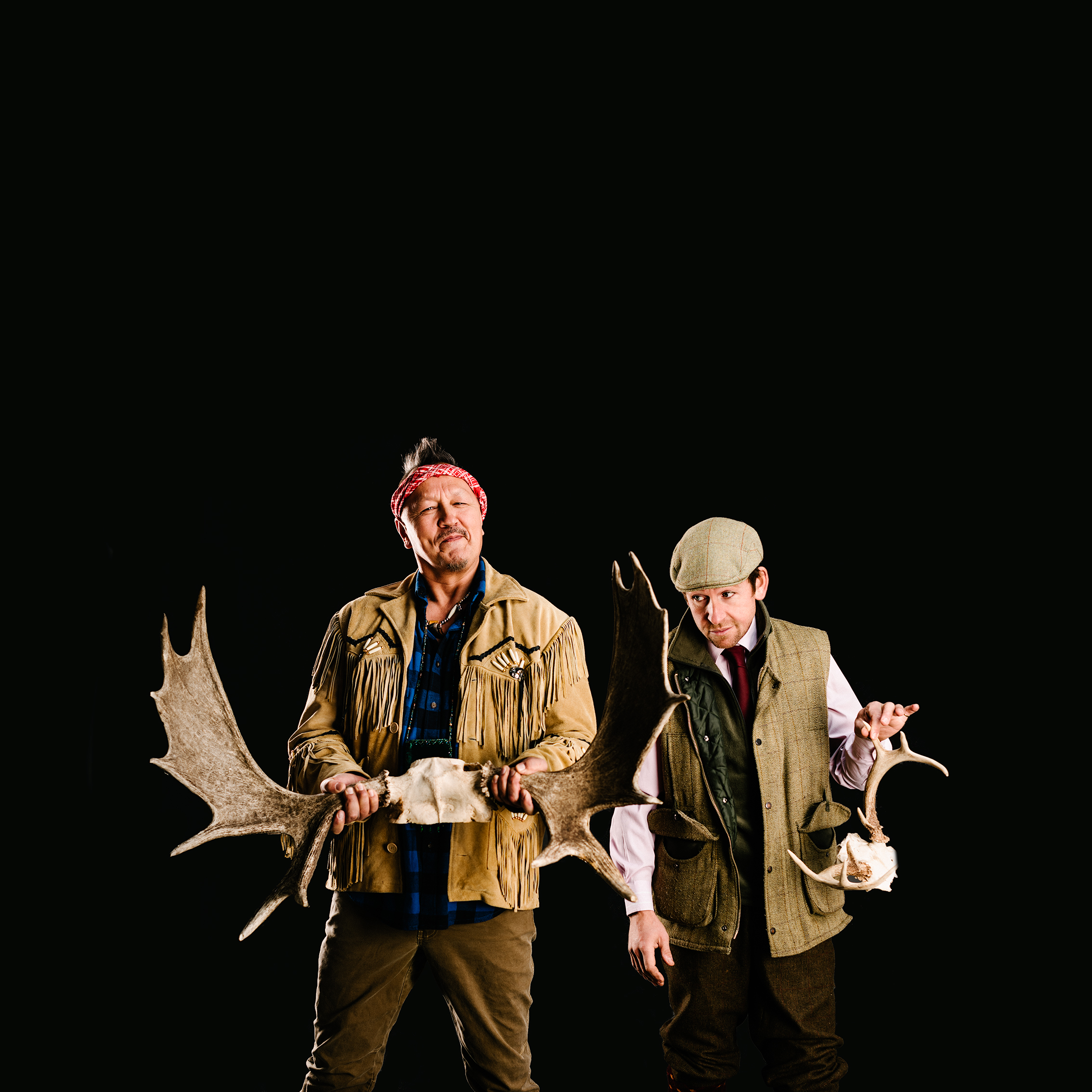

Ward, the founder and CEO of Animikii Indigenous Technology, used to feel quite alone as an Indigenous person in the tech industry, but groups like the First Nations Technology Council are helping equip communities to join the rapidly growing field.

Animikii is a digital agency that strives to support social innovation through Indigenous technology. Animikii (ah-nih-mih-key) means thunderbird in Anishinaabemowin, and the coastal logo was created by Nlakapamux artist Andrew (Enpaauk) Dexel.

"The majority of our team are Indigenous, and almost half of the company are women," Ward told National Observer in an interview at Animikii's working space in the Songhees Innovation Centre in Victoria, British Columbia. "We're only ten people, but we're a diverse group, and to our knowledge, we're the largest Indigenous-focused digital agency on Turtle Island."

Animikii, a for-profit company, is also a registered B Corp (a new corporate model that balances purpose and profit). Animikii focuses its work around a social mission to support and uphold Indigenous communities in the tech sector, and in 2018 the team of ten completed over 600 hours of volunteer time, through community events, workshops, coding camps for youth and pro-bono work.

After running his own web development business back in the late 90s, Ward worked in California's Silicon Valley for a few years, where he experienced capitalism and materialism at its most intense, he said.

"We called it candyland. I was there for the dot-com boom, attended start-up launch parties, and was paid way too much money for a young 19 year-old kid," he said. "I was there for the crash of the dot-com boom too... and I decided to move back to Canada and use my skills for the benefit of the community that raised me. I wanted to give back and leverage technology for the benefit of all Indigenous peoples."

Indigenous peoples have always been technologists, Ward said, with a history of entrepreneurs trading across nations and running their own businesses that extends to the present day, often grounded in culturally-defined worldviews.

"Canadians don't always think of Indigenous peoples as technologists and entrepreneurs, but we're reclaiming those identities," he said. "We have always adapted to new changes in society, and different economic opportunities. This country was founded on Indigenous entrepreneurship and business relationships."

Ward said Indigenous peoples have always exercised sovereignty, but that many forms of self-determination, whether cultural or economic, got stripped away through colonial systems that Canada is only beginning to meaningfully grasp.

"As we reclaim the label of inventors and technologists, we're able to put an Indigenous lens and worldview on the creation of these technologies," he said.

Self-determination and data sovereignty

Ward said Indigenous self-determination in a technologically-advanced world necessarily involves data sovereignty.

Animikii focuses on developing custom software that empowers their clients rather than relying on off-the-shelf software and online services from the likes of Google and Facebook, which often claim data as their own.

Information related to and relevant for Indigenous communities can't always be shoehorned into an existing mainstream framework, he explained.

"We empower our clients to work how they want to work and do what they need to do, through our custom software," he said, calling their commitment to Appropriate Technology "sovereignty in action."

People don't always realize how much capability there is to control data - from the design of something, to its sharing capabilities, he said. Technology influences culture and culture influences technology, and it can be used as an "equalizer," permitting Indigenous peoples to represent themselves and share their own stories, he explained.

Animikii was the digital media agency for the popular film Indian Horse, an adaptation of Ojibwe writer Richard Wagamese’s award-winning novel. The team designed the film's poster, and built and designed their website.

The Animikii team also developed an interactive website for the Gord Downie and Chanie Wenjack Fund and the San'yas Indigenous Cultural Safety Training website.

"We get asked by different groups to develop databases and data collection tools, when there are concerns with privacy or data being hosted outside of Canada," Ward explained. "Data sovereignty involves the design of data, collection of data, sharing capabilities, limiting access, security practices, encryption... all that."

Ward said Nations or Indigenous groups he has worked with have shared concerns around partnering with government agencies, which often dictate how data is collected, uploaded, or stored. Sometimes, people have struggled to even access their own data, he said, and there has been worry that sensitive information, like band membership, economic activity, land registry and land usage, could be used against communities too.

When Animikii develops custom software, they always grant software ownership to clients and data ownership is always theirs.

"When I started Animikii in 2003, as an Indigenous technologist, it was a very lonely place," Ward half-joked. "Now we're seeing a lot of Indigenous youth choose technology as a career path. It's becoming a not-so-lonely place now... it's a vibrant space, the tech scene, and we're attracting more and more talent."

First Nations Technology Futures

B.C.'s technology sector employs more than 100,000 people across more than 10,000 companies (more than oil and gas, forestry, and mining combined), contributing nearly $15 billion annually to the provincial economy.

Yet as of 2016, Indigenous peoples represented less than one per cent of the entire B.C. tech sector, and in 2018 only 1.2 per cent of Canada's tech workers identified as Indigenous. By comparison, Canada's 2016 census counted almost 5 per cent of the overall population as Indigenous, and there are arguments that the official census stats may be lower than the reality.

In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada called on the corporate sector to adopt the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples as a framework to ensure Indigenous peoples have equitable access to jobs, training and educational opportunities.

The First Nations Technology Council (FNTC), an Indigenous-led not-for-profit organization, decided to address the gross misrepresentation of Indigenous talent in the tech space. On Jan. 22, 2018, the FNTC announced an investment of over $7.1 million from Employment and Social Development Canada, towards the Foundations and Futures in Innovation and Technology (FiiT) program, a digital skills training program aimed at increasing Indigenous representation in B.C.'s rapidly growing tech sector.

Denise Williams, CEO of the FNTC, told National Observer that the council spent years conducting relationship-based research around which communities had access to reliable technologies, including functioning, sustainable Internet access, as well as which skills were needed to engage with the tech sector.

The FiiT program, delivered through partnerships with several post-secondary and training institutions including Royal Roads University, the Nicola Valley Institute of Technology, RED Academy, and Lighthouse Labs, offers entry-level training for Indigenous peoples living in B.C. in six fields in the tech sector.

Foundations and Futures

FiiT is a combination of two programs - Foundations and Futures. Foundations, a 12-week program, introduces students to computer basics, web development, digital marketing, software testing, network technology and GIS/GPS mapping, and helps them choose a career path.

Futures provides more focused hands-on learning environments with various industry partners, like the RED Academy and Lighthouse Labs. The Futures training is meant to offer accelerated hands-on training that prepares students for an entry-level position in the tech sector.

Animikii hired one of the first graduates of the Futures program and provided two bursaries for students in the first cohort. Ward also worked closely with the FiiT program, as an early advisor.

Indigenous peoples are the youngest and fastest growing demographic in Canada, and with the right training and mentorship, the FNTC believes that Indigenous peoples can fill an expected talent shortage in tech-related jobs, while empowering their cultures, home communities and nations.

The curriculum around each topic covered in the FiiT program was built by Indigenous curriculum writers, making it a "decolonized approach to education pedagogy," said Williams, who is Quw'utsun and English/Scottish. "If one of the streams really resonates with a student, they move from the foundations course to the futures cohort, which is very focused on their field."

Williams said some community members have expressed concern around losing their youth to jobs outside of home communities. "If nations had reliable and affordable Internet connections, youth could stay home and work, and continue developing their skills and growing businesses," Williams said.

Jonathon Ollerhead was one of the first people to graduate from a program funded through the FNTC's Futures program, in September 2018. Ollerhead, who is Inuit and Métis, said the program, which he completed at RED Academy, was "intense."

"As soon as you enter, you hit the ground running," Ollerhead told National Observer over the phone. Ollerhead wouldn't have been able to do the training program at the academy had he not received funding from the FNTC, he said. "You learn about Google Analytics, creating websites, search engine optimization, advertising, social media ads, content creation and video... I really enjoyed it. I'm a better designer now that I understand the whole process."

Lauren Kelly is the acting director of the Skills Development program for the FNTC. Kelly said the council's skills-development programs have seen the stories of success they had hoped for when they first got started.

"This program, this skills exploration... it's doing what it's intended to do, which is to inspire young people to take tech careers," Kelly said, saying that some of the graduates have been able to return home to work remotely in their communities after completing the program. "That's the whole point we do what we do," Kelly said.

Comments

VPN Delivers Freedom, Protection & Fast, Uninterrupted Speeds

Steer clear of hackers with protection from a VPN

STOP Paying Monthly for Your VPN - Get A lifetime subscription and Never Pay Again

http://bit.ly/2V69WsV