Thank you for helping us meet our fundraising goal!

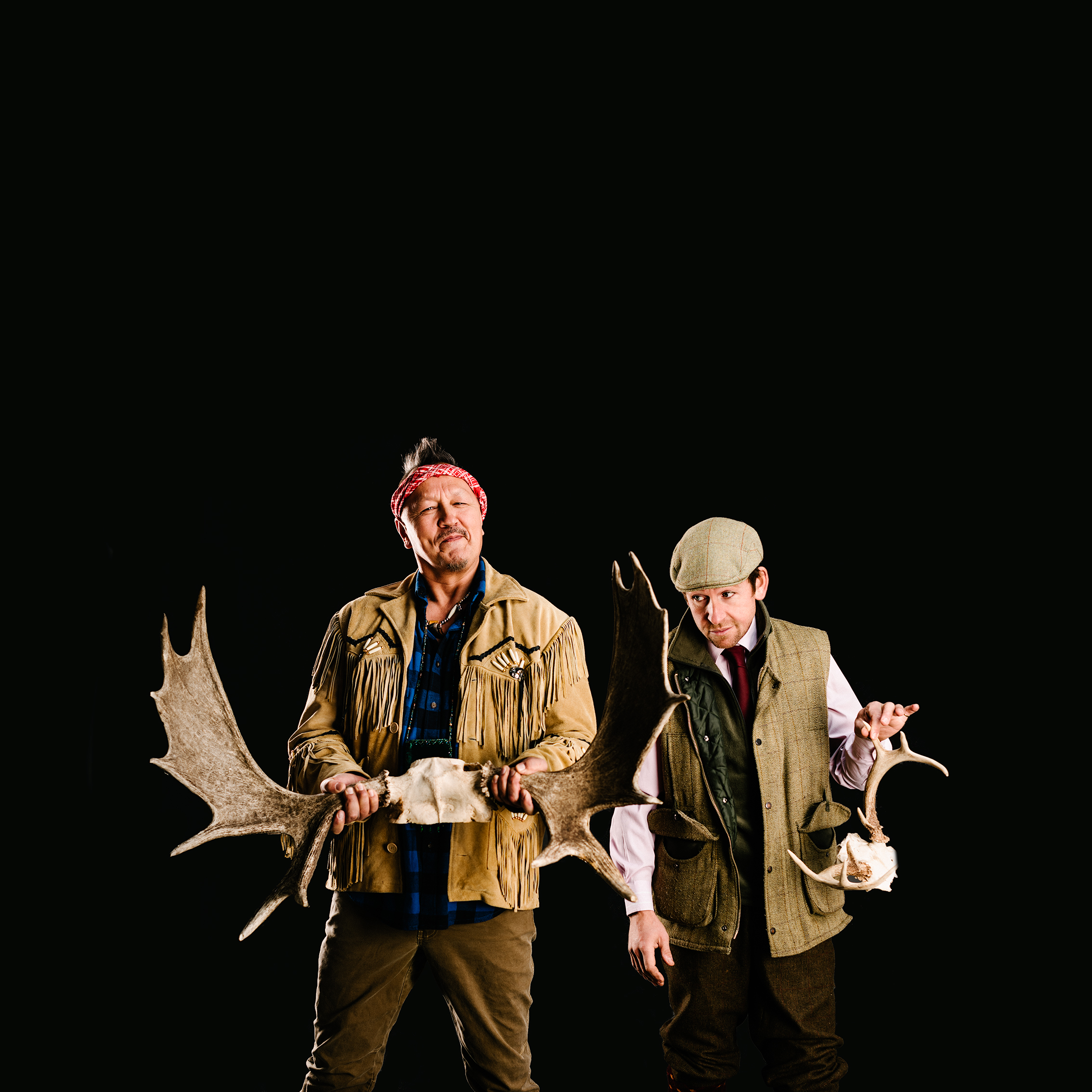

Kyle Powys Whyte, an Indigenous scientist and climate change expert who was one of the co-authors of a staggering report about global warming for the Trump administration, says that people trying to solve the climate problem need to rethink their strategy.

In an interview with National Observer, Whyte, a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation in Oklahoma, said he has noticed how politicians, climate scientists and environmentalists are working too often in a crisis mode that leads them to rush. The end result, he said is that they fail to consider the relationships, based on consent and reciprocity, that are vital to lasting solutions.

Specifically, he said that many policies and proposals fail to acknowledge strategies and solutions from Indigenous peoples, which he said are often focused on restoring and promoting more ethical and just relationships.

"People try out more and more solutions and they're often still harmful to Indigenous peoples, even though the intentions are supposed to be about solving problems," he said.

Whyte referenced a Special Report published last year, by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) as an example of how climate scientists fail to incorporate Indigenous knowledge in their research and strategies towards solutions. The report, which found that humanity had less than 12 years to stop some of the worst impacts of climate change, included some references to Indigenous knowledge, but treated it as an afterthought, he explained..

"Somehow we get Indigenous knowledge thrown in at the very end," Whyte said. "So again, we're being referred to as people, who are primary benefits of the global community, to provide information that will improve climate scientists' studies of climate change...and we're even listed last."

Whyte also cited the United Nations program aimed at reducing emissions from deforestation through the implementation of a forest degradation program, a plan adopted by governments around the world without sufficient consent from the people most affected.

"It's a conservation program for people to get payments for keeping forests and not chopping down forests, and they rolled out this program all over the world. But in most countries where you have forests, you have Indigenous peoples living in those forests," he said. "A payment for a conservation program is not going to work if there hasn't been political reconciliation between tribes and the nation state. If the relationships between them are still poisonous — if there's not consent, trust, reciprocity, then they're not going to be able to organize a conservation program."

He spoke to National Observer before giving a presentation about Indigenous climate justice at the University of Victoria on Feb. 8, 2019.

"When people feel something is really urgent, or crisis-oriented, they tend to forget about their relationships with others," Whyte said. "In fact, most phases of colonialism are ones where the colonizing society is freaked out about a crisis, like when the hydro power in the United States was put in in the thirties, forties and fifties, because of the threat from the Soviet Union, which displaced Indigenous peoples due to the reservoirs from the dam."

Whyte is an associate professor of Philosophy and Community Sustainability at Michigan State University. He is involved in a number of projects with the Climate and Traditional Knowledges Workgroup, Sustainable Development Institute of the College of Menominee Nation, Tribal Climate Camp, Michigan Environmental Justice Coalition, Humanities for the Environment, and the Consortium for Socially Relevant Philosophy of/in Science and Engineering.

He serves on a number of boards and steering committees, including the Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga (New Zealand’s Māori Centre of Research Excellence), The Center for Indigenous Environmental Health Research, Facilitating Indigenous Research Science and Technology, the Sustainable Michigan Endowed Project, the National Indian Youth Council, the Pesticide Action Network, and the U.S. Federal Advisory Committee on Climate Change and Natural Resource Science.

His research, teaching, training, and activism addresses moral and political issues concerning climate policy and Indigenous peoples and the ethics of cooperative relationships between Indigenous peoples and climate science organizations. Whyte was an author on the fourth National Climate Assessment and worked with the US Global Change Research Program on a report the Trump administration tried to downplay last fall.

As a part of the Climate Traditional Knowledges Work Group, Whyte works to produce guidelines and information and to provide mediation between Indigenous groups and climate scientists, in ways that support Indigenous self determination. A document, Guidelines for Considering Traditional Knowledges in Climate Change Initiatives was submitted to the Department of Interior Advisory Committee on Climate Change and Natural Resource Science in May 2014.

The report informs climate scientists on things like "Free, Prior and Informed Consent," Indigenous rights, culturally-appropriate terms of reference, writing and reviewing grant proposals that recognize the value of traditional knowledges, and acknowledging the risks for Indigenous peoples and traditional knowledge carriers in climate change and climate change strategies.

A lack of reciprocal relationships

Whyte added that proposals about using geoengineering to slow down climate change were another example of a problematic approach. He was referring to geoengineering technologies that are being assessed as temporary measures to reduce the severity of certain climate change impacts, "solar radiation management" (SRM) or to remove some of the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, "carbon dioxide removal" (CDR).

Other geoengineering techniques are ocean fertilization, an approach to CDR, and even techniques like Bioenergy and Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS), and afforestation, Whyte said.

Whyte published a paper looking at the ways in which Indigenous people are "discussed when people put approaches that geoengineering on the table." In his research, he found, that "in the world of geoengineering, everybody is concerned with whether Indigenous people agree with geoengineering or not." Most people involved with geoengineering solutions, ask whether they'll go along with it or fight it, he said, rather than whether or not there has been consent established.

"Nobody asks whether the researchers and the countries that propose different approaches to geoengineering have good enough relationships with Indigenous people for an Indigenous community to even feel that it had the voice to consent, to decide or to express what it thought about geoengineering," Whyte said. "So how could anybody propose geoengineering as a way to a clean energy future, sustainable future, if reconciliation hasn't occurred with Indigenous peoples and there's no respect for Indigenous sovereignty?"

Whyte also said he has found that when tribes implement renewable energy programs like solar, they face a problem finding immediate buyers for their energy, because meaningful relationships aren't in place.

"We're still living in an atmosphere marked by discrimination, where people don't look to tribes as entities you could buy energy from. Most tribes are still struggling with getting our energy from other people," Whyte said.

Whyte cited the controversial Site C hydro dam in northeastern B.C., as an example of the issue of consent and self determination.

In a letter issued Dec. 14, 2018 the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination elevated a call to suspend construction of Site C, highlighting permanent harm to the land rights of Indigenous peoples in the Peace River region.

"People all of a sudden proposed hydro power and these energy solutions that just run rough shot over the reality of lacking relationships with Indigenous peoples," Whyte said.

Whyte worked on reviewing the U.S. National Climate Assessment, a summary of the impacts of climate change in the U.S., now and in the future, where he and others looked at Indigenous testimonies, literature, minutes of meetings and more. He said they found that what actually makes Indigenous peoples "vulnerable to climate change" are institutional barriers.

"You can't understand Indigenous climate vulnerability, without understanding that it's much more of a function of the failings of the U.S. or state or local governments, and their relationships with Indigenous peoples," Whyte said. "Governments still haven't created a space for Indigenous people to exercise self determination and run their own programs, their own efforts, use their own legal, political, cultural traditions, to figure out how to be resilient in the face of environmental changes."

It's about relationships and understanding

Is it too late for Indigenous climate justice?

"Well yeah, it is actually too late, because if climate justice is about restoring, repairing and creating new relationships, then because we're not focused on that, then it is too late," Whyte said. "In achieving climate justice or adapting to climate change, it's really not about how bad the storm is or how high a sea level rises, it's about whether the relationships within a society are based on ethical values and norms that will allow for the type of coordination that you need to respond."

There are contrasting worldviews at play, Whyte said, which create roadblocks to mutual understanding, the recognition of Indigenous knowledges and the functioning of reciprocal relationships needed to address climate issues.

Indigenous peoples, he said, live with a different sense of time. While many non-Indigenous peoples think of time as focused on the last 200 years, many Indigenous traditions and peoples think over thousands of years, and have stories and teachings based around a fluid concept of time and the relationships embedded throughout time.

"The reason people get all hung up on the urgency of climate change, is because they think that it was white people a couple hundred years ago who were the first people to even realize what climate change really is and who were the first people to study it," Whyte said.

Some philosophers and climate scientists, Whyte said, call climate change "unprecedented," like it's never happened before, and say all the climate problems are because of cognitive things, like greed or ignorance, but never about a breakdown in relationships.

Whyte said when he looks to his own culture, to the oldest Anishinaabe stories, many are related to climate change. Whyte referenced one of his old migration stories, about movement, motion, changing location and place.

"It's a story about climate change. Each time we moved from place to place, we encountered a new set of ecosystems, new habitat. A lot of our stories are actually about encountering a new place. If you try to control it, you're not going to have a lot of success," Whyte said. "But if you actually tried to relate to it, learn from it and appreciate the independence of the nonhuman world, as well as the people there, you're going to be able to adapt to that new ecosystem and deal with the changes in the environment you're encountering."

When you move, the environment changes around you, Whyte said. But from an Anishinaabe worldview, there's a moral and political response to those changes, he said, adding that at every layer of his traditions, Indigenous peoples were thinking about societal organization, to be as adaptive as possible to seasonal change and the changes across the seasons over years.

Many Indigenous peoples' governments are based around seasonal systems, not on a single government all year round, or a rigid set of rules that attempt to control the environment. A fluid system of government can only be possible through the relationships people have with each other, and the nonhuman world, operated at a highly moral level, he said.

"So the idea is, if your relationships with others are consensual, trustworthy, reciprocal, they're accountable, that's how you ensure fluidity and adaptability," he said, which is how many Indigenous governance systems were able to occur across huge regions and continents, in constant exchange of information. "Connection isn't about change and fluidity, but about moral responsibility."

Someone who believes that it's only relatively recently that we've been dealing with climate change is also probably someone who thinks we don't have a lot of experience or wisdom to cope with it, Whyte said.

"For us, studying environmental climate change is a part of how society's organized. Climate and environmental sciences are some of the oldest," Whyte said. "We don't understand the way time unfolds in a static linear way. Imagine, if the way in which you told time, was based on cues you got from the seasons..."

The changing seasons act as cues to particular social activities, like harvesting, hunting, fishing, and other social coordination, Whyte said, all of which are threatened by a colonial, linear, static relationship to time.

"Imagine if you understood time differently, forgetting about the clock, the days and months, but think about organizing yourself through environmental changes and longer term trends," Whyte said. "The qualities of relationships are the generators of fluidity, not just with climate, but with gender identities, sexual lifestyles, and all the aspects of who we are."

So, why do we propose climate solutions and strategies, if just, ethical and functioning relationships aren't in place? Why do environmentalists stand side-by-side with Indigenous peoples against certain projects where interests are aligned, but not to fight for treaty rights, or against sexual violence, or efforts towards self determination?

If there's no trust, consent, reciprocity, and accountability, Whyte said, sustainability and climate justice cannot be achieved.

If we're genuine in our efforts to achieve climate justice, Whyte said, we need to focus on kinship, and relationships based on respect and reciprocity, otherwise, it is too late for Indigenous climate justice.

But he is not without hope, believing that a "culture of consent" and accountability can be taught to all peoples, and that Indigenous peoples have rich histories, experiences and knowledge around adaptation, conceptions of and relationships to time and the non-human world, which everyone might learn from.

Climate change, he stressed, is about a breakdown in relationships and a profound lack of consent, and if we want to address the state of the planet, we need to stop running around in crisis-mode, but take the necessary steps to develop more just and ethical relationships.

Comments

An interesting unattributed quote in the Guardian the other day - it’s easier (for the British?) to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism. My addition to that - this lack of imagination makes it doubly hard for Western society to be part of any climate solution.