Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

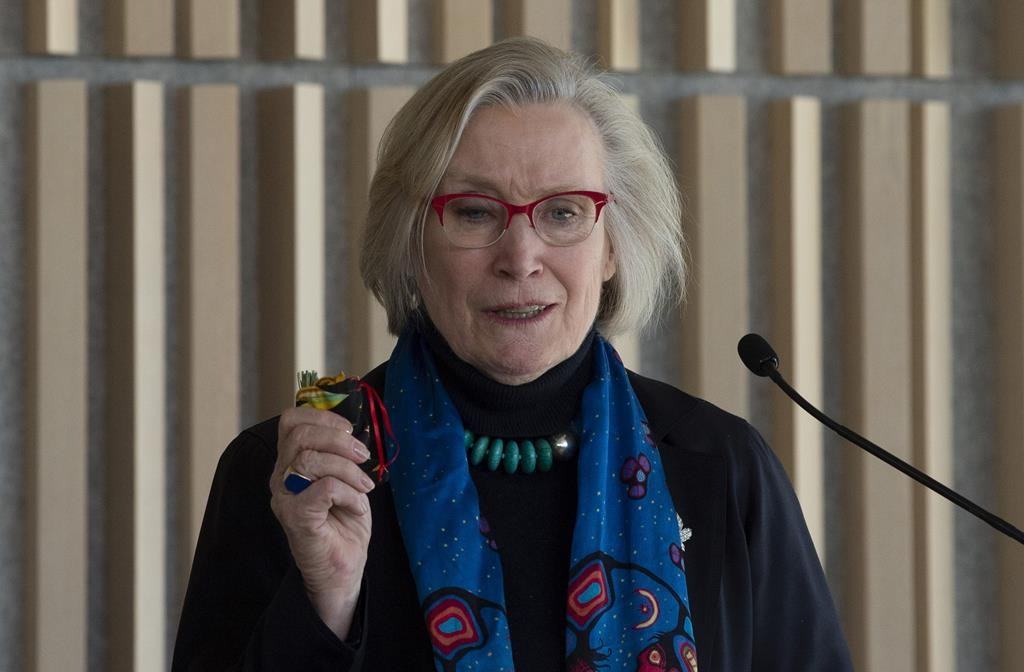

A $200-million component of the settlement for abuses at federally run schools for Indigenous children should help address the long-term pain of male survivors, Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Carolyn Bennett said Thursday after a regional chief sounded the alarm this week about a lack of supports aimed at Indigenous men and boys.

Nearly 200,000 Indigenous children attended more than 700 "Indian Day Schools" beginning in the 1920s. Unlike children at residential schools, day-school students got to go home at night, but many endured trauma, including, in some cases, physical and sexual abuse.

On Tuesday, as the government announced plans to compensate people who attended the day schools with payments of up to $200,000, a regional chief for the Assembly of First Nations spoke candidly about the abuse he endured.

Roger Augustine, who began attending a day school near Miramichi, N.B. at age six and is now regional chief for New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island, said he is "very concerned" about other men living with the aftereffects of abuse. He said he was bullied and beaten up constantly as a day-school student.

There is increased awareness about the "very important" issue of missing and murdered Indigenous women after years of public indifference, he said, but he remains worried about young Indigenous men and boys who do not feel they can speak about what happened to them.

"They're out there, lost," he said. "They don't even know where they are going to get their food to eat that night."

Discussions led by survivors such as Augustine give men and boys permission to seek help, Bennett said Thursday in an interview, noting the federal government heard similar concerns during sessions held ahead of the inquiry into missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls.

"I think these conversations are now becoming more out in the open," Bennett said, point to the documented links among abuse and shame, substance abuse, violence and incarceration.

Many day-school students had no idea they were being mistreated as children, Augustine said.

"A lot of us, a lot of young people don't know what it was, at the time, that was happening to them," he said. "They didn't know what they were faced with."

Bennett said Thursday she was moved by Augustine's story and pointed to the $200-million investment the government is making in a "settlement corporation" for healing, education, and legacy projects in honour of day-school victims, which should include help for men who suffered and are suffering.

On Wednesday, a group representing Indigenous day-school victims issued a statement expressing concerns about the compensation process, including that it believes each claimant should be allowed to choose a lawyer to assist him or her.

In Halifax on Thursday, Bennett said survivors felt strongly they should not need lawyers to navigate the settlement process and they did not want to be retraumatized by a complex claims process.

"This isn't about defending yourself — it's a paper exercise," Bennett said. "Anyone who writes in their application about physical or sexual abuse will receive what they are entitled to."

For his part, Augustine said his healing will never be over.

"You never stop," he said. "PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) and all the other things that you talk about, you grow up with it, you live with it and it never ends."

—with files from Michael MacDonald in Halifax

Comments