Thank you for helping us meet our fundraising goal!

First Nations and cities that have seen costly and damaging oil spills are supporting British Columbia's efforts to require permits for companies transporting hazardous substances through the province.

The B.C. Court of Appeal is hearing a reference case that asks whether the province can create such a system, which would require companies to file disaster response plans and pay for any damages.

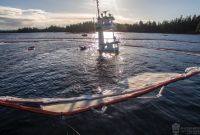

Heiltsuk Nation Chief Marilyn Slett said a spill in her community revealed gaps in federal response. The tug Nathan E. Stewart leaked 110,000 litres of diesel fuel near Bella Bella in late 2016.

"The day the spill happened, our people were out there. They were out in their boats, they were there trying to help with any of the recovery," Slett said in an interview.

"What we noticed is there isn't room for Indigenous people and Indigenous governance within the spill response regime."

The Heiltsuk and other First Nations, the cities of Vancouver and Burnaby and the environmental group Ecojustice argued on Tuesday that the Appeal Court should uphold B.C.'s proposed permitting regime. B.C. says the goal of the system is not to block oil and gas projects but to protect against disasters.

The governments of Canada, Alberta and Saskatchewan have not yet had an opportunity to deliver arguments, but they say Ottawa — not provinces — has jurisdiction over inter-provincial projects such as the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion.

Canada says in court documents that the proposed amendments to B.C.'s Environmental Management Act must be struck down because they give the province a "veto" over such projects.

Slett said she believes that if B.C.'s proposed system had been in place when the Nathan E. Stewart sank, the recovery would be further along now. She also hopes the province's regime, if approved, will incorporate Indigenous knowledge of their territories.

"Our people know our areas. They know the tides. They know the weather patterns," she said.

City of Vancouver lawyer Susan Horne told court that the municipality supports B.C.'s proposal because it would ensure local and First Nations governments are properly resourced to respond to spills and are fully compensated for damages.

"Local governments, like the City of Vancouver, are on the front lines of emergency response for their communities," she said.

The Trans Mountain pipeline expansion, purchased by the federal government for $4.5 billion, would triple the capacity of the existing line from the Edmonton area to Burnaby and increase tanker traffic in Burrard Inlet seven-fold.

Horne said Vancouver borders Burrard Inlet and a diluted bitumen spill would create a toxic plume that would risk the health of anyone in close proximity and delay response until the threat had subsided.

A relatively small diesel spill in English Bay in 2015 required a response from 12 city departments and cost Vancouver more than $569,000, she said, and ship owners have not repaid the city yet.

Michelle Bradley, representing the City of Burnaby, said diluted bitumen can sink and become submerged in shorelines. It's also flammable and the city's fire chief has raised concerns about the possibility of a blaze at the Trans Mountain tank farm, she said.

Burnaby has already been affected by a spill from Trans Mountain in 2007 when a contractor struck the line and caused 224,000 litres of heavy oil to spew into a residential area, she said. The company relied extensively on Burnaby first responders, she added.

The city does not currently have the capacity to respond to a disaster from the expanded Trans Mountain project, but B.C.'s proposed system would help ensure it was ready, Bradley said.

"The environmental damage caused by releases of hazardous substances will be local, not national," Bradley said. "The governments closest to those communities should be empowered to enact legislation to protect those communities from harm, and to exceed national norms for environmental protection."

Joseph Arvay, a lawyer for B.C., told court earlier Tuesday the proposed amendments would not allow the province to refuse to issue a permit without cause. Permits would only be withheld or revoked if the operator failed to follow conditions imposed upon it, he said.

If the operator finds the conditions too onerous, it can appeal to the independent Environmental Appeal Board, or in the case of Trans Mountain, the National Energy Board, Arvay added.

The energy board has set up a process where Trans Mountain Corp. can argue that a condition is too burdensome and violates the special status of inter-provincial projects, he said.

"The NEB effectively gets the last word ... but it's going to be condition by condition."

Comments