Just before 2 a.m. on June 20, 2016, a foul-smelling cloud of toxic chemicals from a Syncrude oilsands plant began slowly drifting north towards the hamlet of Fort McKay, 10 kilometres away.

Six weeks earlier, devastating wildfires ripped through Fort McMurray, forcing a massive evacuation of the oil town and an emergency shutdown of the company’s Mildred Lake plant. By late June, workers were trying to restart the operation.

It didn’t go as planned.

An estimated 10,400 barrels of untreated petrochemicals were released into a waste pond. It created a plume of toxic air that could cause headaches and possibly long-term health risks for anyone on its path.

“This is an unprecedented event,” wrote an Alberta Energy Regulator (AER) scientist in an email obtained through freedom-of-information legislation.

The plume contained hydrogen sulphide, which can cause respiratory issues at lower concentrations and death at higher ones. It also held high amount of hydrocarbons — a group of compounds, some dangerous, found in crude oil. Two of the most toxic are toluene, which affects nerves, and benzene, a carcinogen.

Officials couldn’t tell if they were in the cloud that day.

They also couldn’t determine if the amount of toxic chemcials in the plume would trigger an emergency until it reached Fort McKay, 10 hours after it was released, a National Observer/Star Calgary investigation has found.

By 11:30 a.m., a local official emailed colleagues with a warning.

“I personally cannot stay outside the (office) and breath[sic] the air outside, it is pretty bad,” wrote Ryan Abel, a staffer at the Fort McKay First Nation, in an email obtained by freedom-of-information.

“Definitely going to cause headaches, etc. for those breathing it in.”

Two hours after he sent that email, federal officials at Health Canada decided to issue an air quality advisory for Fort McKay.

Insiders from within the Alberta Energy Regulator would later say that the incident highlights one of the key problems facing the oil-rich province, which has long-claimed to have the strongest environmental regulations in the world. They say that pressure and lobbying from industry and economic interests are trumping science and strong oversight, putting public health and safety at risk.

The incident also highlights gaps in air quality monitoring, despite federal and provincial efforts in recent years to improve how governments are overseeing an industry in a region that holds the world's third largest reserves of crude oil after Saudi Arabia and Venezuela.

In the aftermath of the incident, the regulator fired its chief scientist, a toxicologist who, according to internal records, tried to warn the community of the danger. The regulator then sought to replace her with a job posting that called for someone with lower qualifications.

AER staff clashed

For years, residents of Fort McKay have complained about foul-smelling air pollution from the oilsands plants that surround it, though long-term health effects have never been proven.

A post-mortem report leaked to National Observer and the Star also noted that the incident occurred after some oilsands operators “pushed back” against the AER’s efforts to coordinate the resumption of industrial operations in a safe and orderly fashion. Insiders at the regulator said that the industry was lobbying the regulator to get plants restarted as fast as possible.

As the chemicals inched towards the town, AER staff clashed over whether they should warn the community, say insiders interviewed by the investigation. They didn’t have the data to know if the toxins in the plume would put human health in danger.

“We really didn't know what the risks were going to be (for Fort McKay),” said one person with direct knowledge of the AER’s decision-making process, speaking confidentially for fear of professional reprisal. “(At that time) there really was no human health risk-based decision-making at the regulator. It was either you killed someone or you didn't.”

Internal emails also show Syncrude didn’t communicate with Fort McKay until an hour after the plume had arrived. It was “far too late under these circumstances,” said Abel, the Fort McKay First Nation staffer, in an email obtained by freedom-of-information.

Since then, Syncrude says it has updated its protocols for communicating with Fort McKay and restarting the plant. The AER said it takes its environmental responsibilities seriously and is working to improve overall air quality in the area — a longstanding issue for the community, which is surrounded on all sides by oilsands operations.

But oilsands operators are exempt from rules set by the AER that compel companies to warn communities if they release toxic substances, so Syncrude faced no consequences from the regulator.

“This could have potentially impacted the community’s ability to enact an emergency response plan and undertake appropriate safety measures,” said a passage of the leaked AER draft report on the incident.

'I never sleep with my windows open'

Syncrude spokesman Leithan Slade said the company is “continuously improving” its notification protocols. The AER, which warned Fort McKay five hours after the chemicals were released, said the community “would have been notified immediately if there was a public health risk.”

That afternoon, Health Canada issued an air quality advisory warning Fort McKay residents to “consider sheltering indoors.”

In response to the National Observer/Star findings, Alberta Environment and Parks spokesperson Matt Dykstra said the government would conduct a study into air quality near Fort McKay, but didn’t give details.

Fort McKay First Nation declined to comment, and Abel also declined to speak about the incident. The McKay Métis didn’t respond to requests for an interview.

The Cree, Dene and Métis people who live in Fort McKay used to survive by hunting and trapping — now, good relationships with oil and gas companies have allowed the community of 750 to prosper. The First Nation’s businesses brought in $506 million in gross revenue from 2012 to 2016, according to a Fraser Institute report.

Industrial emissions are also a fact of life for Fort McKay, a community of 300 homes and 750 people.

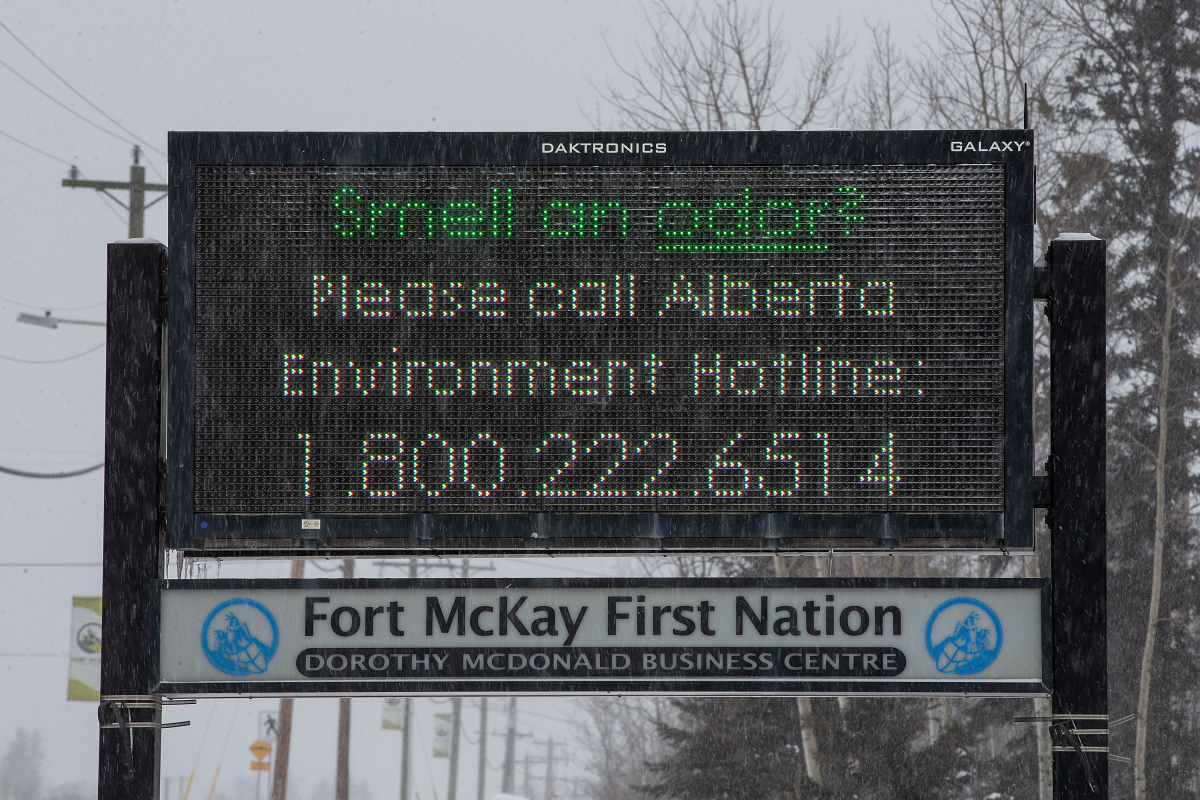

A sign outside the First Nation office warns residents to report odours with a 1-800 number. The Athabasca River Valley can act like a funnel for emissions, channelling releases from various oilsands facilities towards Fort McKay.

Syncrude’s Mildred Lake plant is one of 11 oilsands facilities within a 30 km radius, with more planned and proposed. The company is owned jointly by Suncor, Imperial Oil and Chinese-owned CNOOC and Sinopec.

Syncrude is also one of the largest operators in Canada oilsands, which are estimated to comprise more than 98 per cent of the country's estimated 173 billion barrels of oil reserves, according to the federal government. The government also says that the oilsands sector is Canada's fastest growing source of climate-warming greenhouse gas emissions.

In Fort McKay, visitors can see the First Nation’s wood and glass administrative building, a shiny, new daycare centre and tidy homes with pickup trucks in the driveways. A few times per year, every member of the nation gets a share of the profits — in June 2018, individuals got a cheque for $1,700 each, the nation’s website says.

“People are in positions where … they're scared because they don't want to bite the hand that feeds them,” said L’Hommecourt.

The affluence comes with a cost: air quality in Fort McKay sometimes exceeds air quality thresholds for toxic hydrocarbons like benzene and toluene, and for other harmful substances like hydrogen sulphide, found the 2016 study by the AER and Alberta Health.

Residents often smelled ammonia-like odour of cat pee, sewage, sulphur and tarry bitumen. They had headaches, burning eyes and sore throats. Sometimes they wondered if they should evacuate, the study said.

“Not a week goes by where you don’t smell anything,” said Jean L’Hommecourt of Fort McKay First Nation.

Sometimes it’s ammonia — one leak of it from Syncrude in 2006 sent four Fort McKay children and a teacher in to hospital. Other times, it’s sulphur or gasoline.

The AER received 172 air quality complaints from Fort McKay between 2010 and 2014, a government report publicly released in 2016 found.

“I never sleep with my windows open... because you never know what what's gonna come into your house in the middle of the night,” L’Hommecourt said.

“I don't trust the government and I don't have faith in them... It's always the same outcome. It seems like they say whatever they want to.”

Companies 'pushed back'

The AER/Alberta Health study, published September 2016, included recommendations for improving air quality that are still in progress. It did not mention the Syncrude release that happened a few months earlier.

AER scientists “were not allowed” to include it, or to publish the draft report about the incident that was obtained by the investigation, said the AER insider.

The AER said “finalizing the (draft report) was no longer necessary” because it publicly released the AER/Alberta Health study.

In March 2017, the AER fired the toxicologist who warned Fort McKay about the plume and co-authored the unreleased report, Monique Dubé. The scientist hired to replace her as chief environmental scientist has degrees in economics and engineering, according to his LinkedIn.

“The AER is conflicted. Its dual mandate to both grow the industry and protect the environment means having to choose one over the other,” said McMurray Métis president Gail Gallupe in a statement responding to Dubé’s firing.

“With (Dubé) as chief environment scientist, we knew that we had a serious voice for the environment within the AER. We worry now that her voice is gone.”

The AER has said said it’s “confident” in the current chief scientist’s abilities, but it has declined to comment on Dubé's departure.

On June 20, 2016, many Fort McKay residents hadn’t yet returned home from the wildfire evacuations. Aside from a short local news story — which didn’t mention the impact on Fort McKay or the severity of the air quality readings — the chemical release from Syncrude received little public attention.

The lingering wildfire smoke meant the air quality was already worse than normal. The process of starting up an oil production facility can cause emissions spikes, adding to the problem.

The AER had been trying to stagger several companies’ startups and monitoring air quality around the clock.

It hadn’t been smooth sailing. The AER’s draft report notes that some companies “pushed back” when asked for details on their plans. And some operators didn’t tell the regulator quickly enough when they released chemicals.

The first warning about Syncrude’s chemical release came at 1:38 a.m., when a company representative called the AER to report a gasoline-like smell. Though Syncrude told the AER it didn’t evacuate anyone, the company “had any workers in the area go to other facilities/buildings where they would be safe,” the AER draft report said.

Officials would later determine that naphtha, a solvent, had been released into a pond used to dump waste. The naphtha is supposed to be separated in a ‘recovery unit’ before entering the tailings pond, but there was an “operational failure,” AER briefing documents said.

'It wasn't a leak'

Slade, the Syncrude spokesperson, said the incident was part of a “planned” but “complex” restart. “It wasn’t a leak.” There was an issue that led to the machinery not working as planned, but the recovery unit didn’t fail, he said.

“Since that incident, we have updated our flushing practices as well as how we notify Fort McKay,” said Slade.

At about 4 a.m., the deteriorating air quality set off alarms at the Wood Buffalo Environmental Association (WBEA), which does air monitoring on behalf of the province.

In the Wood Buffalo region, oil and gas facilities have air monitors along their fencelines. The one at Mildred Lake’s boundary was recording levels of hydrogen sulphide three times greater than the provincial standard — “sufficient evidence” that the release would cause odours off-site, the AER draft report said.

It also picked up maximum hydrocarbon readings about 75 times greater than the background conditions.

“These values are extremely high,” noted the regional environmental association staffer who reported the readings to the AER at about 6 a.m., according to the draft report.

In this case, the air monitor at the Mildred Lake fenceline couldn’t differentiate between harmless hydrocarbons and ones that could be poisonous to breathe, the AER draft report said.

It measured total hydrocarbons, for which there’s no air standard.

That day, an air monitor within the plant picked up large amounts of benzene, enough to clear workers from the area. And later, once the plume reached Fort McKay, toluene was measured at levels above the upper limit of the community monitor.

But there were no air monitors between Mildred Lake and Fort McKay that would tell scientists whether the chemicals released were harmful. The only air monitor that could do that was at the centre of the community. And as of 3 a.m., the wind had been blowing towards it.

AER scientists decided the safest option was to warn the community. But their bosses rejected the idea, saying it wasn’t clear there was any risk, two insiders at the regulator said.

Eventually, at 7 a.m., Dubé — then-chief environmental scientist — circumvented her bosses and sent an email to the Fort McKay First Nation. It had been more than five hours since Syncrude reported the release to the AER.

“Air quality exceedances — IMPORTANT,” read the email, obtained through freedom-of-information legislation. “We expect odours in the community this morning and today.”

“Another possible air quality episode for Fort McKay — yikes!” replied someone else in the email chain. Their name and the organization they represented were redacted.

Hydrocarbon levels were “the highest I’ve ever seen recorded in the region,” they added.

'It's getting bad there'

Environment and Climate Change Canada staffers scrambled to access real-time air monitoring data for the Fort McKay community station after a 9 a.m. request from the AER.

“Could you please call me when you get these (emails),” an AER scientist wrote. “There has been an upset at one of the plant sites… This is an unprecedented event with respect to (hydrocarbon) levels.”

“The portal has been updated to provide access to our real-time data… as fast as possible,” a staffer from the federal Environment Department replied.

Officials waited as the plume crept north, air monitors gradually picking up more and more of the sulphur compounds and hydrocarbons. It reached the community at 10:45 a.m.

With the right data now in hand, public health officials raced to figure out the risk: though not acutely toxic, there was a “strong odour, suspected health effects associated,” the AER draft report said.

“It’s getting bad there,” an Environment and Climate Change Canada employee wrote in an email at 1:30 p.m.

Though oil and gas companies in Alberta must follow a set of emergency response guidelines that in some cases could include evacuation, oilsands operators are exempt from those requirements.

In this case, it would have been up to Syncrude to decide whether to tell Fort McKay about the chemical release. It did so at about noon, 10 hours after it reported the incident to the AER.

At 1:30 p.m. — 12 hours after the incident occurred and five and a half hours after Health Canada was first told about it — the federal agency issued its advisory.

The federal government published its warning two hours after air monitoring confirmed the odour in the community. It spent the time assessing the risks and drafting the statement, said Indigenous Services Canada spokesperson William Olscamp in a written statement. (The agency has since taken over Health Canada’s former responsibilities for First Nations communities.)

Alberta government didn't say if it would introduce new standards for hydrocarbons

No injuries were reported. Though the plume caused an exceedance of air quality guidelines at the Mildred Lake fenceline, it didn’t breach any standards in Fort McKay for hydrogen sulphide or specific hydrocarbons.

Dykstra, the Alberta Environment and Parks spokesperson, did not answer questions about whether the government plans to create standards for hydrocarbons.

The smell lessened over the course of the afternoon, but the air quality advisory remained in place for nine days. On June 28, 2016, the day before it was dropped, a Fort McKay representative reported that a “significant odour” was “causing throat irritation after being outside for several minutes,” the leaked AER draft report said.

In general, energy companies are required to notify the AER of chemical releases — though there are exceptions, such as emissions from restarts or emergencies. The agency posts incidents, investigations and actions taken against companies on a public database available online.

An AER communications strategy document instructed staff to say the agency was “conducting an investigation,” but no record of one appears in the database.

The AER didn’t answer questions about the investigation’s outcome and said the incident didn’t meet the criteria to be posted.

In a statement, the AER said it is working to improve overall air quality in Fort McKay through 17 recommendations from its year-long study of Fort McKay air quality, and three from the leaked report about the June 20, 2016 incident.

The provincial government has clarified emergency response roles between agencies since the incident, and created a 24-hour notification system that informs the Fort McKay community if air quality readings reach a trigger level for certain substances. Residents can also access real-time air quality data from the monitor in the community.

But the government hasn’t created trigger levels for hydrocarbons. It also hasn’t closed the air monitoring gaps that led to the initial confusion on June 20, 2016, which means that Fort McKay continues to face the same risks today.

Dysktra, the Alberta Environment and Parks spokesperson, said the government’s review would be publicly available once complete.

The provincial regulator and the Alberta government have come under fire in recent months after a National Observer/Global News/Star investigation revealed the cost of cleaning up the province’s oilpatch could reach an estimated $260 billion. It’s also faced criticism for allowing oilsands companies to pursue an unproven technology to deal with their toxic waste, also the subject of a Star/National Observer investigation, and for leaving legal loopholes that allow companies to abandon old wells without cleaning them up.

The Fort McKay incident raises further doubts about the independence and the ability of the NDP-led government to regulate oil and gas, said Alberta Liberal MLA David Swann.

“The government has some explaining to do,” he said.

The Jason Kenney-led United Conservative Party — which is leading in polls for the current provincial election, and has pledged to replace the AER's board of directors with one focused on "cutting red tape" — didn't respond to several requests for an interview on the National Observer/Star Calgary investigation's findings. The centre-right Alberta Party declined to comment.

Keeping gas masks at home

L’Hommecourt, the Fort McKay resident, said she doesn’t see how anything short of establishing new limits on chemical emissions will help.

“Do you want to depend… on (the government) to protect you or are you going to take measures into your own hands?” she said. “We have to be ready for a catastrophe.”

L’Hommecourt said the access to air quality data brings her some comfort. But still, she worries about the long-term effects of the constant industrial odours, and keeps gas masks at home.

Meanwhile, new oilsands mines around Fort McKay continue to be approved: Suncor opened its Fort Hills mine in September, the same month that the AER held hearings for a new mine proposed by Teck Resources Ltd.

“How (can officials) say they're going to make things better or air quality better when they're approving more and more projects,” L’Hommecourt said.

“Your roots are here but at the same time they're being ripped out from under our feet.”

Editor's note: This article was updated at 2:06 p.m. ET on April 8, 2019 to correct that there are 11 oilsands facilities operating within a 30 km radius, north of Fort McMurray, Alberta.

Comments

Dr. Dube was also the person who recommended air testing of gases reaching the flare stack on fracked wells in Alberta. This testing ("Flowback Study") was completed, but the AER has had results for two years, and has never released them to the public.

There was a photo of a smoggy L. A. and a clear sky Fort McMurray as if to demonstrate how clean tarsands oil is, however it is clear from the map that Fort McMurray is neither down wind or downstream from the plants

Only independent monitoring with predetermined acceptable levels of toxic release in place will work . These items should be part of their corporate safety system that allows them the privileged to operate. A violation will allow the corporation to face criminal negligence charges for violating their corporate safety system that currently keeps them out of jail when someone dies at work or i imaging as a defense from a large spill . .Currently any release is putting lives at risk with no punishment for that risk or monitoring of the severity of that risk . The companies and governments have left us no choice but to move this into criminal court . That being said the corporate safety system has to be taught and shared with the citizens of this reserve so they understand the guidelines the company has imposed on themselves to guarantee they will cause no harm. The deterrent is that criminal charges will land someone in jail hopefully the manager responsible with huge fines going to the company for not controlling its managers . This would improve the safety culture as well as the leadership culture to understand they have a responsibility to be accountable for their actions . If you want this injustice we are now being played with to stop , to find accountability , you need to use the rules in place ( corporate safety system ) and the criteria the National energy Board . Knowledge is power . We also need whistle blower protection so the employees can find some protection from negligent employers that put the workers at risk . Governments really don't run the country or our economy ,but they have to enforce the law . learn the Charter of rights Life, liberty and security of person

7. Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of the person and the right not to be deprived thereof except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice and the criminal code 216 ,217,217.1 219 understand these laws .

Inexcusable situation, ....on several fronts:

1. Instrumentation to continuously sample air quality and differentiate and quantify presence of toxins exists... one example is gas chromatography, and that technology has existed for many decades... more modern and effective instrumentation may easily exist, but the technology I've cited is available and Syncrude can afford it, ...so can the AER. This equipment can alarm toxic conditions in real time...even if staff are not available to babysit it.

2. Syncrude is 'continuously improving' it's communications with Fort McKay.... who is buying THAT line of justification? They have been in continuous operations since 1979.... have they not got their methodologies and protocols in place DECADES ago to warn Fort McKay of immanent danger when it occurs? If not, why the hell not? They have a vulnerable residential community in their air shed, they have a legal duty to protect that population or someone's head (or more properly ALL responsible 'heads') needs to be served up on a plate. And that person should NOT be the toxicologist on staff with the AER !! ... this falls to Syncrude, and the other lease operators who do business in extraction and upgrading in the Fort McKay region.

The AER is a lapdog. And for them to fire the scientist who had the INTEGRITY to duly warn the residents of McKay to take adequate and necessary precautions is a culpable disgrace. The person/s who made the decision to fire the scientist needs/need to be publicly identified. There needs to be a provincial all-party inquiry into the firing of this scientist and they need to be either reinstated (if they wish their position back) or they deserve generous punitive damages for loss of reputation and unwarranted dismissal.