Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Did you know sheep can protect vulnerable tree seedlings better than chemical sprays?

The Saulteau First Nation sure does. Last year, the B.C. band invested in a herd of sheep and teamed up with two shepherds experienced in sheep veg-management to reduce the use of toxic chemicals in their territory.

Vegetation management is an important reforestation activity in that it involves preventing wild plants from stealing sunlight needed by young tree seedlings. The seedlings are planted in most new forest sites established in areas that have been logged or affected by wildfire, insects and disease. Toxic chemical sprays are one form of vegetation management, but there are non-chemical options available and growing in B.C.

Sheep-based vegetation management is one of many positive ways their people resist the violent implications of oil and gas, mining and forestry companies. The Saulteau First Nation is located in the heart of the Peace River Region in northeastern B.C., also known as "the industrial zone," Juritha Owens told me during an interview in her home.

Owens is a councillor for her band who shares all portfolios with the other councillors. The Saulteau First Nation has a unique governance system, infusing a traditional clan system into the way people are elected onto council, an insight of the relatives before her, making sure that fair representation came from each family in the band. But that's a story for another time and certainly not mine to tell.

Owens cares about health.

In dealing with her own health issues, she has done a fair bit of research on food, agriculture and, most specifically, the ways forest industries use toxic chemicals to manage the vegetation that chokes out young trees on their plantations.

Owens watched documentaries, read research papers, spoke to her community and came to understand that products like Monsanto's Roundup were harmful to the land, the animals that eat the toxic vegetation and indeed, the humans who eat the wild animals and plants. She was particularly disturbed by the use of glyphosate, the active ingredient in Roundup.

She found out 16,000 hectares of B.C. forests were sprayed with glyphosate in 2015. (In 2017, the number decreased to 10,000 hectares.)

The World Health Organization has warned that glyphosate is likely carcinogenic. It also has genotoxic, cytotoxic and endocrine-disrupting properties — fancy ways of saying it messes with your genes, cells and major glands.

Owens said she and her community have witnessed first-hand the negative effects of the use of chemicals on their wild game. Many jurisdictions across the world have banned or restricted the use of glyphosate, including the Netherlands, Germany, France, Portugal, El Salvador, Argentina and Denmark.

She asked: Why is Canada slow to move?

The old ways were the best ways

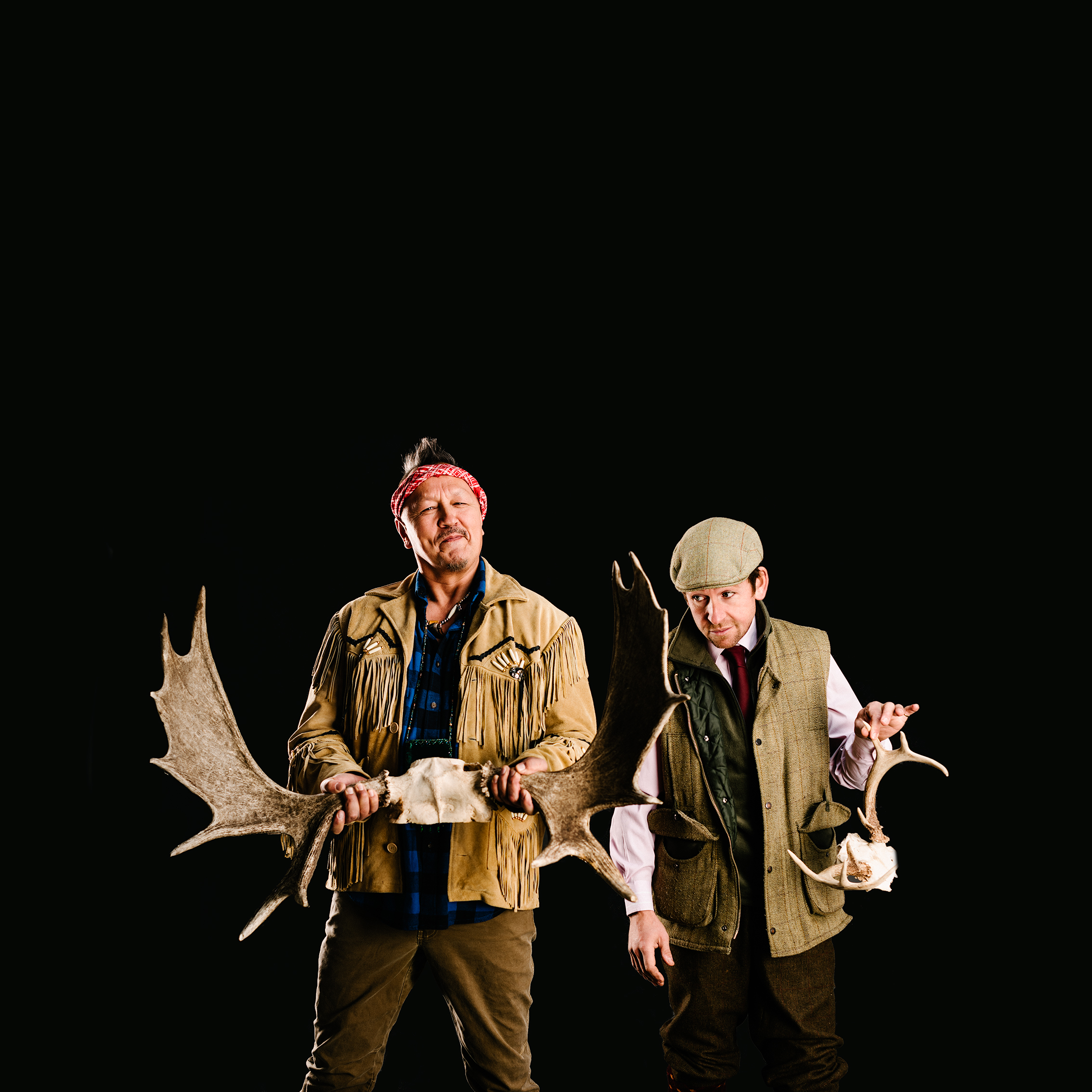

At the same time Owens started to ring the bell on the negative effects of chemical sprays, a man named Dennis Loxton and his partner in sheep-vegetation management Agnes Marie Thomas were grazing rented sheep on the community forest for West Fraser forestry company.

John Stokmans, Saulteau's Forestry Resource Technician asked West Fraser's silviculture manager Don Scott if he could tour the operation and learn more about how sheep can be used as a non-chemical vegetation management strategy.

Forestry companies use sprays like Roundup to deal with the lush vegetation, which can shoot up six to eight metres high, taking over the young trees and starving them of light. The seedlings, small and fragile in the early stages of life, can't compete. They collapse, break, die.

That's where the sheep come in. Shepherds and their herd dogs spend months at a time with the flocks, guiding them to eat the vegetation around the seedlings, a task they are more than happy to handle. Stokmans saw how sheep could be used as a viable industry for Saulteau, which would employ members and contribute to food security, he wrote in an email.

After speaking to two separate councils, Stokmans arranged a meeting between Loxton and Saulteau's chief and council, to discuss the idea of a world class sheep operation. After a successful meeting, Saulteau hired Loxton and Marie Thomas to help the band start their sheep farm.

"We generally have about eight guard dogs per flock," said Loxton, who is originally from Australia, and who has spent most of his life in the bush. "These sheep completely leave the trees behind, but eat everything else. That's the beauty of it, it's completely natural."

"There's big money in vegetation management and sheep," he said, as we watched one of their trained herd dogs send a concerned mom and her lost lamb back to the pack. "It's the cheapest non-chemical vegetation-management tool, and it's the most efficient."

"We created a five-year strategic plan," Owens explained in her home on June 15. "We knew the first three years we would be investing into the initiative, but on the fourth and fifth years, we could start making income and have worthy revenue through contracts with forest companies and B.C. Hydro."

The sheep do the work that would otherwise be done by chemicals. While there is no regulatory requirements saying chemicals need to be sprayed, there is a requirement for trees to be free from brush.

Don Scott is a silviculture forester for West Fraser Mills, a lumber company that operates on the Saulteau First Nations traditional territory. The company signed a contract for sheep grazing in some areas they harvested, which will start at the end of the month.

"We have been sheep grazing since the mid 90’s and have found it to be a very viable option in terms of the brush management techniques available to foresters," Scott wrote in an email. "We also employ a local farmer and have over 1300 sheep grazing in another location."

Last year, West Fraser worked with Saulteau to help train their flock, which was quite young at the time, he said.

"One thing about their flock was that the sheep learned to eat Canada Reed grass. Normally this species of grass is not overly palatable to sheep, it is not their preference as a food source, but Saulteau First Nation's sheep seemed to go after it," Scott wrote. "Reed grass is harmful to planted seedlings, and they struggle to get established in these areas."

Moving to enlarge the grazing vegetation management industry will take some time, he said, but it's worth the effort.

Agnes Marie Thomas — originally from France and has spent decades working with sheep — has been working for the Saulteau First Nations for one year, long enough to see it's working, she said.

They grazed three months in the bush and have seen their sheep do 100 hectares. Loxton and Thomas have been apprenticing young Saulteau members in herding the sheep and managing the farm. Loxton said when they returned from the bush, the other sheep were healthier than ever under the supervision of the apprentices.

The band hasn’t yet recouped its initial investment, which was significant. Beyond the cost of new infrastructure, including an expensive barn for the sheep to sleep in during winters, they also needed to hire community members to run the operation — and they needed a lot of hay.

At the moment, the band owns 274 sheep, plus 100 lambs, but they plan to increase the flock to 1,200. The herd was sourced from a Hutterite farmer by the name of Bill Walter from a farm called Gold Ridge Farm in Turin, Alberta. Eventually, Owens said, they'll make revenue from their wool and potentially their meat, if they decide to sell their meat to niche markets.

For her, it's the best solution to replacing toxic chemicals that are just one particularly poisonous part of an industry onslaught in her region.

"The old ways were the best ways. As industry grew here, it was all about making as much money as fast as possible, and nothing was done in a healthy way. It's all about money for some people," Owens said. "These sheep, the dogs they use, the land — it's a healthier connection than spraying herbicides and pesticides and killing everything."

Thomas agreed: "When you work for 25 years in the bush, you see a thing or two," she told me, sitting at a table near her trailer home, near their flock of sheep. "When you really think about it, the way it has all been managed in the past is just madness. We have to stop that. The sheep break down the old trees, make organic matter, spread it in the manure... it's symbiotic."

Smqwaqw Justice Van De Riet, 16, has been apprenticing with Loxton and Thomas for the past couple of months. He said he loves his new job and how he gets to spend time outside, with the animals, learning about the land. It beats some other boring summer job, he told me.

Loxton's 69 years old and Thomas is 60. They both said they plan to retire down the line, which was the band's intent all along, to have Saulteau members trained to be able to run and take over the project.

"We're lucky to have Dennis and Agnes as teachers and we're fortunate they're willing to stay with us until they're comfortable passing it on," Owens said. "I hope what we're doing has a ripple effect in other nations and communities with herbicides in their backyards."

There's a lot of people still living off the land, hunting, fishing, picking berries, she said, and they need to do everything they can to protect what's left.

This article was updated on July 4 at 2:40 p.m. ET to include comments from John Stokmans, Saulteau's Forestry Resource Technician.

Comments

Perfect!! This country should ban Roundup and be done with it. The powers that be have always tried to teach the indigenous peoples of the world. Well I think it is long overdue that we start to learn something from them and join them in the fight to save this planet.