Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

When James Feistner and his partners started Mercury Espresso Bar more than 10 years ago, they wanted to be green.

So they decided to spend a few more cents per cup so that customers of the café on Toronto's eastside could sip their on-the-go lattes and cappuccinos from biodegradable cups.

"I always wanted to do the right thing," Feistner said. "I have to try… so I can sleep better at night, I've got to do something."

But a couple of years later, he learned the city does not collect and sort the throwaway items into compost and they instead end up in landfill. Feistner's well-meaning efforts to reduce his livelihood's waste output were foiled.

(City officials say they have always used an anaerobic digestion process that cannot break down the cups.)

Feistner keeps trying new strategies. This winter, he bought 48 ceramic mugs from a local pottery class at 25 cents apiece to hand out to regular customers at his current café, but only one remains in circulation, and a sustainable long-term solution evades him. It is a dilemma shared by coffee retailers worldwide, who sell their caffeinated hot drinks in some 250 billion throwaway trash products a year.

Toronto, along with most of the rest of Canada, sends most of the millions of disposable coffee cups its residents discard each year to landfill. (The exception is British Columbia, which has put more of the onus on producers, rather than consumers, to deal with the end of their products' lives, something known as extended producer responsibility.)

The game changer?

Yet, a new product from a Finnish paper mill might solve the coffee industry's problem, which multinational giants including Starbucks have thrown millions of dollars at in recent years.

Kotkamills Oy started up its board resin business about three years ago, just as a global revolt against disposable and destructive plastic waste was taking shape, CEO Markku Hämäläinen told National Observer last month.

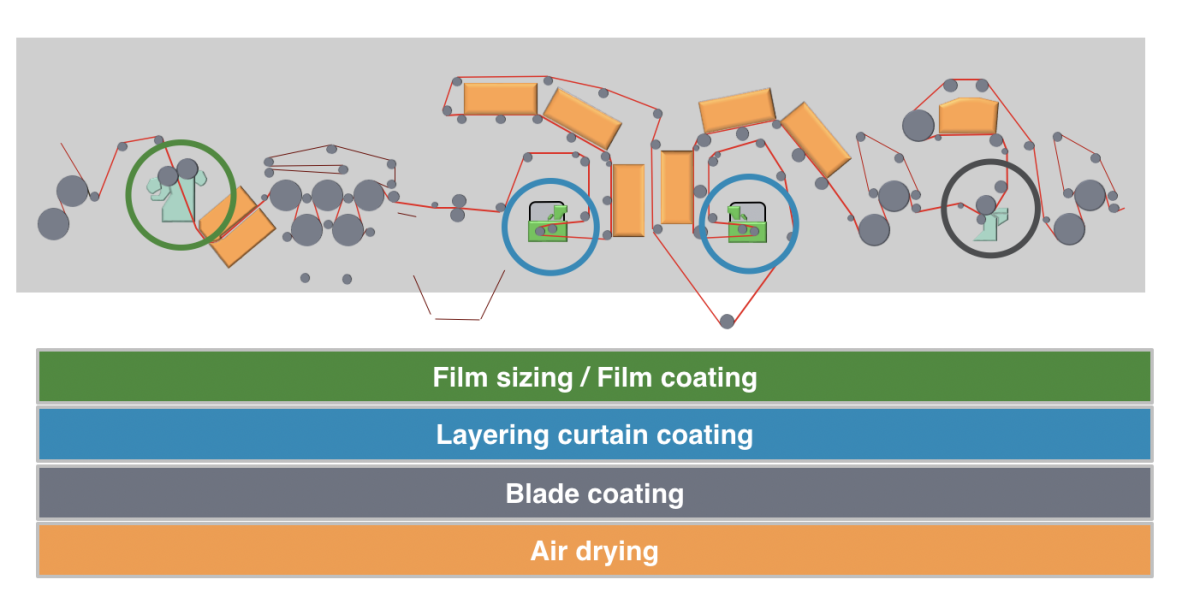

The company, based in Kotka, a 90-minute drive east of Helsinki, only started trials of its cups, which are treated with a water-based layering process, with some small potential buyers six months ago. It is now looking to snag deals with larger companies eyeing a greener coffee-cup solution.

“We have agreed that we won’t mention names, but there are no famous names yet,” Hämäläinen said in an interview about which companies he has been talking to or which are testing his “ISLA Duo” trademarked (patent pending) product, which the company has dubbed “The Game Changer Cup.”

The emergence of Kotkamills' cupstock (and a handful of other innovative potential solutions to the coffee-cup conundrum) comes as cities and countries across the world seek to drastically cut down on the amount of plastic waste they, their businesses and citizens discard. That plastic waste has ended up in massive trash islands in the middle of oceanic currents and shown up in the bodies of fish and other sea creatures.

The ISLA Duo cups don't contain any harmful plastics or waxes but still retain heat, matching the quality of existing options while far exceeding them in ease of recycling, Hämäläinen said over lunch during the World Circular Economy Forum, which took place in June in Helsinki.

The chief executive said he expects orders to start flowing soon, predicting the company’s board resin business — which can also produce alternatives to plastic for all manner of food packaging, including for salads, hamburgers and ice cream — to push annual overall sales to 500 million euros in the next two years, from 355 million euros last year.

He said a typical polyethylene hot coffee cup costs 3 euro cents (4.5 Canadian cents) to produce, and the water-based extrusion coating process would add another 1.5 euro cents to cups made from Kotkamills' cupstock. The coating can be applied with existing cup-making machines.

What gets recycled?

In 2016, around 25 million tonnes of non-hazardous waste was sent for disposal across the country, according to Statistics Canada. That volume consisted of 14.7 million tonnes from industrial, commercial and institutional sources, roughly similar to the 2014 totals.

Some 4.7 million tonnes of that 2016 waste was plastic; only 9 per cent of it was ultimately recycled (mechanically or chemically) and 4 per cent incinerated for energy recovery, according to a report prepared for Environment and Climate Change Canada by consulting firm Deloitte.

It's not easy to definitively say how large a portion of that waste came from coffee cups, as opposed to single-use plastic bags, straws, drink bottles or the other detritus of a plastic-dependent society.

But those handy receptacles that keep our double-doubles and skinny caffe mochas hot on the move are a major contributor to those waste piles, thanks to a typical process of applying plastic film to the inside of the paper cup. This process makes them neither paper nor plastic in the eyes of recyclers.

Most coffee cups are lined with polyethylene (PE), which is used to waterproof the cup and protect its integrity at hot and cold temperatures. Very few facilities provide the services to separate the plastic from the paper in order to properly recycle them. Some have a wax lining or are biodegradable, but they can be difficult to tell apart from PE-lined ones at recycling facilities.

Canada's big coffee chains

Until now, there has been a lot of talk and little progress to improve the sustainability of takeaway coffee cups among major coffee retailers.

In 2017, Stand.earth, an environmental group, confronted Starbucks executives outside the annual shareholders meeting with a "cup monster" built out of dirty Starbucks cups. The campaign to persuade Starbucks to change its ways continued until the Seattle-based global coffee giant began to take a leading role, investing US$10 million in the NextGen Cup Challenge to identify ways to recycle or compost cups on a global scale, but the company has also sought to blame municipalities for being unable to handle their conventional packaging.

"While Vancouver stands out as (a) leading city that has made cup recyclability a reality, many municipalities in Canada don’t support cup recycling," it said in a statement posed on its Canadian website in March. "Here, Starbucks Canada pays local private haulers to collect and recycle hot cups from its company-owned stores, along with our other recyclable products."

But Monica Kosmak, senior project manager for Vancouver's Zero Waste program, said recycling in the city and elsewhere in the province was managed by Recycle BC, to which producers pay fees to collect items, sort them and sell them to end markets for processing into new products.

She said coffee cups it was obliged to collect in B.C. were collected and shipped abroad, possibly to South Korea, and could not confirm specifically what happens to the cups after that point.

Toronto says on its website that plastic-lined hot beverage paper cups are difficult to sort mechanically at recycling facilities, and that it has been unable to find buyers for the low-quality product. The city said conventional paper mills do not want to take coffee cups as feedstock because the inner liner clogs up the pulping process and dyes in the paper can make it difficult for paper mills to turn cups into other paper-based products.

Shipments of Canadian recycling materials have been turned back from Malaysia and the Philippines recently due to concerns about contamination, while China banned the import of all plastic for recycling several years ago.

Kotkamills was one of 12 winners of the NextGen Cup Challenge, which is also backed by McDonald’s and Coca-Cola. Starbucks has said it will test different green cup options from the design competition in Vancouver, New York, San Francisco, Seattle and London this year.

Representatives for Canada’s other major hot coffee retailers — Tim Hortons, Second Cup and McDonald’s — had varying responses to extensive requests for their comment for this article.

An unnamed representative for RBI Inc. (or Restaurant Brands International), the private equity-controlled vehicle that owns the Tim Hortons, Burger King and Popeyes brands, initially responded enthusiastically, pointing to an announcement the company made in May about its investments in sustainability.

These included a "substantial marketing effort" over the next 10 years to encourage customers to use fewer single-use cups, as well as testing a more environmentally friendly paper cup this year, testing a new strawless lid for iced coffee and rolling out wooden stir sticks.

When asked to clarify or expand upon the reference to a new paper cup and whether it would be plastic-free, the generic email address responded by saying only that "we have no other details to share at this time, but would be happy to connect again when we have more information."

Second Cup is "always looking into new products and options that help reduce our environmental footprint," according to Alexandra Azzopardi from Craft Public Relations, speaking on behalf of the company.

She said Second Cup had recently introduced biodegradable straws and biodegradable cellulose fibre to wrap its sandwiches in cafés in the Quebec market, but did not respond to queries about any plans to migrate to a plastic-free cup.

McDonald’s did not respond to repeated requests for comment, but presents a relatively united front with Starbucks regarding the importance of finding a solution to the problem.

Starbucks said it works to eliminate waste and increase recycling, including by collecting its cups in blue receptacles in most stores and paying a third-party company to process them "to ensure items that can be recycled are recycled, even in municipalities that currently do not support the processing of our current cups."

The company did not clarify if this was to recycle the cups or to ensure they go to landfill and do not contaminate other materials.

Starbucks also offers a 10-cent discount to any customer who brings a reusable cup or tumbler to company-owned stores in Canada.

None of the companies that did respond to queries agreed to requests to interview an executive responsible for sustainability initiatives.

Independent cafés interested

Feistner, who now owns the Might and Main café in Toronto's east end, said he would be very interested to learn more.

"We thought these paper cups were recyclable, and then the city comes back and says, 'You can't recycle these.' So now they're just garbage. So yes, I would be very interested in a cup that's actually recyclable despite the cost difference," he said.

Feistner said he'd be happy to shoulder the cost himself if it meant being able to tell customers their throwaway cup would be collected, processed and reused up to seven times, and questioned why the municipality didn't take the excess of biodegradable cups as a sign it needed to expand or adapt that program rather than shut it down.

"There is no leadership when it comes to environment issues," he said. "People are trying to do what they can at the household level, but us going to the grocery store with reusable bags is not going to save the environment."

He said he pays around $120 for a box of 1,000 16-ounce cups, or 12 cents a cup, and would be willing to pay up to 20 cents per cup if he could tell people they could recycle it.

"If I had to mark up an extra nickel (five cents) on cups to cover the cost, I think people would be totally fine with that," he said.

Max Jordison, manager at the Dark Horse Espresso Bar on Toronto’s Spadina Avenue — the busiest of the company’s six locations across the city — expressed a similar sentiment.

"The majority of our cups just go in the garbage," he said, noting that at least two-thirds of the coffees sold there are taken away in the company’s branded throwaway cups. "I know we go through our recycling and we take all our coffee cups out of it so as to not ruin the recycling."

He said the café had at one point sought to recycle cups via a shredding company that would disperse the heavy, waxy mix with thinner papers from the offices it also serves. This was not a scalable solution, however, as the recycler was unable to keep up with the small chain's output.

Jordison said Dark Horse's Spadina location alone goes through about 1,500 12-ounce cups every week, as well as around 500 eight-ounce cups and another 500 or so of the 16-ounce ones. The cups, printed black with the company's logo in white and red, cost between 13 and 18 cents each.

"If I'm talking for myself, if it was like $10 or $15 more per box, maybe $20 I would be fine with it," he said. That would equate to another two to four cents per cup.

This Dark Horse location, on a main drag for smaller tech companies in Toronto and across the street from a social innovation hub, takes 25 cents off the cost of your coffee if you use your own reusable mug. (Or, put another way, charges you 25 cents to take a cup that is difficult to discard sustainably.)

Jordison said he believes the additional cost for a recyclable cup could be passed on to a consumer willing to pay more to be able to avoid the landfill.

"I do believe that if our cups were recyclable and we charged 10 cents a drink, no one's going to be that upset and some are going to be quite excited about it," he said.

Discus Supply Company, which provides Dark Horse and many of Toronto's other higher-end coffee houses with their cups and other packaging, offers a biodegradable cup but not one that is recyclable.

Founder Mustaali Kanchwala said he would be interested to hear more about the Kotkamills' ISLA Duo when contacted by National Observer for this article.

The voice of the people

Guy Yango, a public-sector employee working from Dark Horse, said his willingness to pay more for a recyclable cup exists on a sliding scale: at five cents extra he wouldn't notice, at 10 cents he would notice but not mind, and at 15 cents he would start to consider changing his behaviour.

The five-to-10-cent range was also acceptable for Carmen Kruk, a loyal Starbucks customer who usually orders a tall blonde roast brewed coffee in her own hardened-plastic reusable mug.

Kathleen Abela and Louie Biteranta, who were enjoying drinks at Starbucks with other family members, agreed that 10 cents would be an acceptable cost for a recyclable cup and said they typically use their own reusable cups.

The limit was five cents for Yitta Rei, a bartender who said a push to replace existing cups needed a compelling story to capture people's attention.

"To convince people to pay for a better cup needs a good story, like with plastic straws and sea turtles," she said outside a Starbucks store.

None of the coffee consumers informally polled by National Observer were aware that most coffee cups are not currently recycled.

Kotkamills' Hämäläinen, who has a post-graduate degree in paper coating, said the technology the company is using is 30 years old, but that larger companies had not done it before on an industrial scale.

He said major companies had made commitments to recyclable packaging they had been unable to meet due to lack of supply.

He's betting his company's future growth prospects depend on being able to satisfy what appears to be considerable pent-up demand.

Editor's note: this story was updated at 7:30 PT on July 3 to include the name of the environmental group, Stand.earth, that played a leading role in persuading Starbucks to look for a coffee cup solution.

Comments

Somehow, cutting down more trees when animal habitat is disappearing all over (including in Finland, Sweden and Norway) doesn't seem terribly progressive. I've seen YouTube footage of destruction of reindeer food, which takes many decades to re-establish: they eat lichens that hang down from old-growth evergreens -- we used to call it "witches' hair," as it was dark in color and resembled matted hair as it hung down.

I remember seeing video footage ... don't remember where, of a Japanese bio-degradable product used for soups and beverages ... it was made of rice and was also edible, if one desired to dispose of it pre-composting.

That might be something worth looking into. I wouldn't compost the corn-plastic-lined ones, without some trialling, in case there was enough glyphosate in it to kill the plants one puts the compost on. (That is how "corn gluten" kills weeds, isn't it?)

https://greenpaperproducts.com/biodegradable-hot-cups.aspx

https://m.facebook.com/nakedcards/photos/fab-infographic-from-plasticfr…

I think we have been searching for the perfect throwaway cup for too long. I don't expect Tim Hortons to provide me with a new toothbrush or new underwear every time I visit.. It is time for coffee drinkers to start bringing their own collapsible cups. I prefer Rocontrip but there are many other designs, and IT IS NOT THAT HARD TO CARRY ONE.