A matter of days after her new city councillor took office, Rida Abboud had been blocked from communicating with him on his Facebook page.

It was the fall of 2017 and Jeromy Farkas had just been elected to Calgary city council. In an early Facebook post, he accused his predecessor of destroying the ward’s records (in fact, the former councillor responded, it was standard practice). Abboud didn’t support Farkas, but as one of his new constituents, she was concerned by the misleading messages.

She decided to send an email to Farkas’s constituency office asking him to stop the divisive rhetoric. When it went unanswered, she decided to reach out to Farkas more directly: in a comment on his public Facebook page.

“I said, ‘At the end of the day, you have been elected in the ward… you need to be representing it,” Abboud said in an interview with National Observer.

“That was what got me banned.”

In short order, Abboud was barred from liking the page, following its posts or interacting with them — important, as Farkas often uses Facebook to ask constituents for guidance. (The councillor didn’t respond to several requests for comment.)

“Being able to single-handedly ban and block people who are being critical of their positions, that's an abuse of power,” Abboud said. “(I felt) annoyed, frustrated and very sickened.”

In the era of social media, Canadians theoretically have more access to their elected officials than ever before. Instead of waiting days for a response to a letter or voicemail that might never even arrive, citizens can reply to politicians’ posts instantly — sometimes even gaining an equally speedy response.

“You never see a politician now without a Twitter handle, practically speaking, but that wasn't the case before. It's all relatively new: the etiquette and the rules, and the technologies and capabilities of these different social media platforms raise different kinds of complications and issues,” Paul Champ, an Ottawa-based civil liberties lawyer, said in an interview. “It is a little bit of a wild west.”

With just a few clicks, politicians can just as quickly shut them out of what often seems to be the most effective way to reach elected officials acting on their and the public’s behalf.

People who spoke to National Observer for this story about being blocked by politicians were not always polite on social media. Though none were abusive or engaging in harassment, they were sometimes frustrated or openly critical. Some even actively supported an opposing candidate or party.

But in every case, they wanted their public representative’s response to an inquiry, a complaint or a point of contention. And there is no legal precedent or policy enforcement in Canada that guides when an elected official can — or cannot — block a citizen.

‘Everybody's using their own judgment on this so far’

Often, there are legitimate reasons for elected officials to want to block or ban someone. Over the last several years, many female politicians in Canada have come forward about online abuse from members of the public. Former Ontario premier Kathleen Wynne was and is among the most targeted, and finds her social media accounts often inundated with homophobic comments and threats of physical violence.

“We tried to block as few people as possible,” Wynne said in an interview with National Observer. “What I learned was that it’s a dynamic conversation. We're not finished with it, there isn't a simple answer to this.”

Wynne said her staff developed their own internal guidelines. Much of her office’s conversations centre on protocol: should Wynne fire back or engage with the “really nasty stuff” that comes across her social media? Should she correct the inaccuracies about her life or her policies?

“Everybody's using their own judgment on this so far,” Wynne said.

“I don't think this is just for one politician to determine. We've got to figure out as a society what we think the tenor of those interactions should be. Over time as a society, we have determined how we interact with each other when we're walking down the street, when we're in public spaces. We've got rules in place that we may not articulate, but there are rules of social conduct. I don't think we have those same rules developed yet on social media. And because of that I think we're all struggling with what's OK and what's not OK.” — Kathleen Wynne

Twitter became highly relevant in politics with the election of U.S. President Donald Trump, who has taken to announcing significant policy changes by tweet before speaking with media outlets. More troubling, in the view of some observers, is how Trump has taken to blocking a widespread group of people for criticism — including journalists, citizens and others.

Last year, an American court ruled against Trump, finding that a public official who blocks a constituent from their Twitter feed is violating the First Amendment’s protection of freedom of speech.

In her opinion, Judge Naomi Reice Buchwald of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York found that the “interactive space” associated with the president’s Twitter account constitutes as a “public forum” under the First Amendment and that the president is therefore barred from blocking speakers from his account.

But cases in Canada haven’t gone that far. The only case that’s reached the Canadian courts involved Ottawa Mayor Jim Watson and three political activists, but was settled before it was decided by a judge.

According to the statement of claim, the three applicants, who have individually been critical of various aspects of Watson’s policies, argued that the Ottawa mayor breached the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms section on freedom of expression by blocking them.

The mayor has said that @JimWatsonOttawa is his personal account, but he regularly uses it to communicate city news. For example, during the 2018 tornadoes, he tweeted information about power outages and other emergency information. Dylan Penner, one of the complainants in the lawsuit, told National Observer he wasn’t privy to this pertinent information during the weather emergency because of the block that happened only days before the tornado hit.

By blocking some residents, the lawsuit alleged, the mayor is denying them critical public information and the "ability to engage in debate concerning municipal issues using Twitter," which the applicants argue is now the main method of communication for public officials. The complainants also argued that blocking them was a breach of their charter rights.

Watson came to a settlement with the complainants and agreed to unblock everyone (“There are no accounts blocked by @JimWatsonOttawa,” his spokesperson said in an email), but the case started a discussion: do elected government officials in Canada have a constitutional obligation to make their social media platforms accessible to all, no matter what?

The lawsuit was “a good warning sign for other politicians,” said Champ, the lawyer leading the case. It was an indication that politicians, political parties and other elected officials had not “adequately turned their mind to the issue” and each goes by “their own arbitrary view of when and how to block people.”

“Because so many people access or consume their information about government through these platforms now,” Champ said, “it’s becoming more important than ever that we really come to grips with how politicians engage with citizens on social media.”

‘They're all adults and they can decide how to interact online’

In the absence of formal guidelines, some parties have made their own rules.

The federal Liberal party, for example, allows some ministers to block in “in the case of bots, abusive or threatening language,” according to a statement from Eleanore Catenaro, a press secretary in the Prime Minister’s Office. The prime minister’s Instagram, LinkedIn and Twitter accounts don’t block anyone, but on Facebook, “profanity, personal attacks, racism and other forms of discrimination will be deleted without warning,” according to the party’s online community guidelines.

The federal NDP didn’t respond in time for publication, but the Toronto Star previously reported the party has an informal policy of discouraging blocking. The Ontario NDP has a similar guideline — “NDP MPPs don't generally block constituents unless they're using abusive or threatening language, and we don't police the members' social media as we'd like them to be as authentic as possible online,” said Oliver Paré, the party’s head of engagement, in an email.

(These party-level policies might explain why National Observer was unable to interview people blocked by NDP or Liberal politicians elected to represent them.)

The federal Conservatives didn’t respond to a request for comment, but in Ontario, the party does not have a guideline for its MPPs, said Ivana Yelich, a spokesperson for Progressive Conservative Premier Doug Ford.

“They're all adults and they can decide how to interact online,” Yelich said.

The situation is more complex in municipal politics, where parties aren’t at play. In Calgary, where Abboud was blocked by Farkas, ethics adviser Emily Laidlaw said the city doesn’t have a social media policy for councillors but will work on one in the coming months.

The 2015 guidance for the city of Guelph's members of council says: "Perhaps the best advice is to approach online worlds in the same way we do the physical one — by using sound judgment and common sense.” That guidance laid the basis for the city of Toronto’s integrity commissioner, who wrote a set of social media guidelines in 2016 telling councillors to generally follow their code of conduct. Neither city made specific instructions about blocking.

The consensus among these few loose guidelines seems to be that without formal rules, public accounts of elected officials should be treated as such: public.

Politicians also have options beyond blocking. They can mute accounts, which allows them to protect themselves from hateful comments without limiting citizen access to information. They can report questionable or problematic behaviour to the social media platform itself.

In a recent post about the issue, Cara Zwibel, director of the fundamental freedoms program at the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, concluded that a Canadian court “might well find a charter violation in similar circumstances since these online spaces have become our new public squares.”

“Blocking a constituent sends a clear message to those who wish to engage with them on matters of policy or otherwise: tread lightly. This kind of chill is terrible for our democracy,” she writes.

In an interview, Zwibel said she recognizes there’s a lot of work to do before a legal precedent is created in this regard. For one, the Canadian charter talks about “government,” so it doesn’t really apply to backbenchers, only members of cabinet and leaders.

“But we need to figure out parameters, and we need to do it soon,” she said.

‘It's simply about accessing your government or being prohibited from doing so’

Jon Liedtke, a Windsor, Ont., journalist, complained to the city’s integrity commissioner last May after the city’s mayor, Drew Dilkens, blocked him on Twitter. Dilkens had turned down his interview requests through more formal channels, Liedtke said, so he turned to social media instead — a common technique for journalists seeking interviews with public figures.

“It's easy to just have baby boomers just tune out when they hear any millennial start complaining about Twitter but it's much, much broader than that,” Liedtke said.

“It's simply about accessing your government or being prohibited from doing so.”

At the time, Dilkens told CBC he didn’t want to “get into” why he blocked Liedtke, but he’d happily speak with “anyone who wants to have a respectful, decent dialogue on issues and be respectful and not be disparaging or bullying or intimidate or harass.”

“It wasn't a matter of harassment,” Liedtke said. “I would never resort to derogatory terms or anything. But you know, I persisted on the issues, just asking questions.”

Liedtke argued that because Dilkens was representing himself as the mayor online, he was barring constituents from engaging with him by blocking them. That complaint, however, was never ruled on — the commissioner closed the case after Dilkens unblocked Liedkte in July.

“It's incredibly unsatisfying, because I wasn't petitioning to the integrity commissioner to get unblocked by the mayor,” Liedtke told National Observer.

“What I was seeking was a firm answer from the integrity commissioner on whether or not elected officials have the ability to block members of community from their social media feeds. And I was hoping to come to an answer as to whether or not social media platforms are treated in the same way as the public sphere.”

Simone Racanelli, a 20-year-old political science student at the University of Toronto, was blocked by her MPP on Twitter last May. At the time, Christine Hogarth was a candidate seeking a seat in the 2018 Ontario provincial election; she was later elected in the Toronto riding of Etobicoke-Lakeshore.

Racanelli, who has volunteered for the provincial and federal Liberal parties, tried calling Hogarth’s campaign to ask which debates she’d be participating in, but said she couldn’t get a clear answer from her staff. (At the time, Metroland Media reported that Hogarth had declined an open debate invitation.)

Racanelli tried Twitter next: “Why do you refuse to say what debate you’re attending, where it is and if it’s open to the public? Your lack of transparency with constituents is unsettling, and not a characteristic I want in an elected official.”

Hogarth first redirected Racanelli to her office, then responded with details of a debate happening later that week. But Racanelli said she checked with organizers, and the debate wasn’t open to the public.

“You could’ve easily just said that instead of choosing to lie,” she tweeted at Hogarth. Hogarth blocked her soon afterwards, and left the block in place after she won her seat in the election.

“My tone was definitely not too polite,” Racanelli said. “(But) that's a fair question to ask anyone who was, at the time, running to be an MPP... part of your job is to communicate with your constituents so you need to be open, accessible.”

In a statement, Hogarth said constituents who are blocked are still welcome to “constructively” contact her by phone, email and letters.

“I personally choose to block anyone who directs abusive, malicious, or harmful language towards me or my staff,” the statement read.

The office of Ontario’s integrity commissioner, which oversees MPP conduct, said there’s no specific policy related to blocking constituents on social media and there haven’t yet been any complaints about it.

But Racanelli said she thinks parties should at least have policies against the practice. Though she said it is more complex because many officials use personal accounts — rather than Watson’s account, which was an official city one — there should still be rules because the accounts are being used for political purposes.

“You shouldn't be allowed to block your constituents because they have a different opinion from you,” Racanelli said.

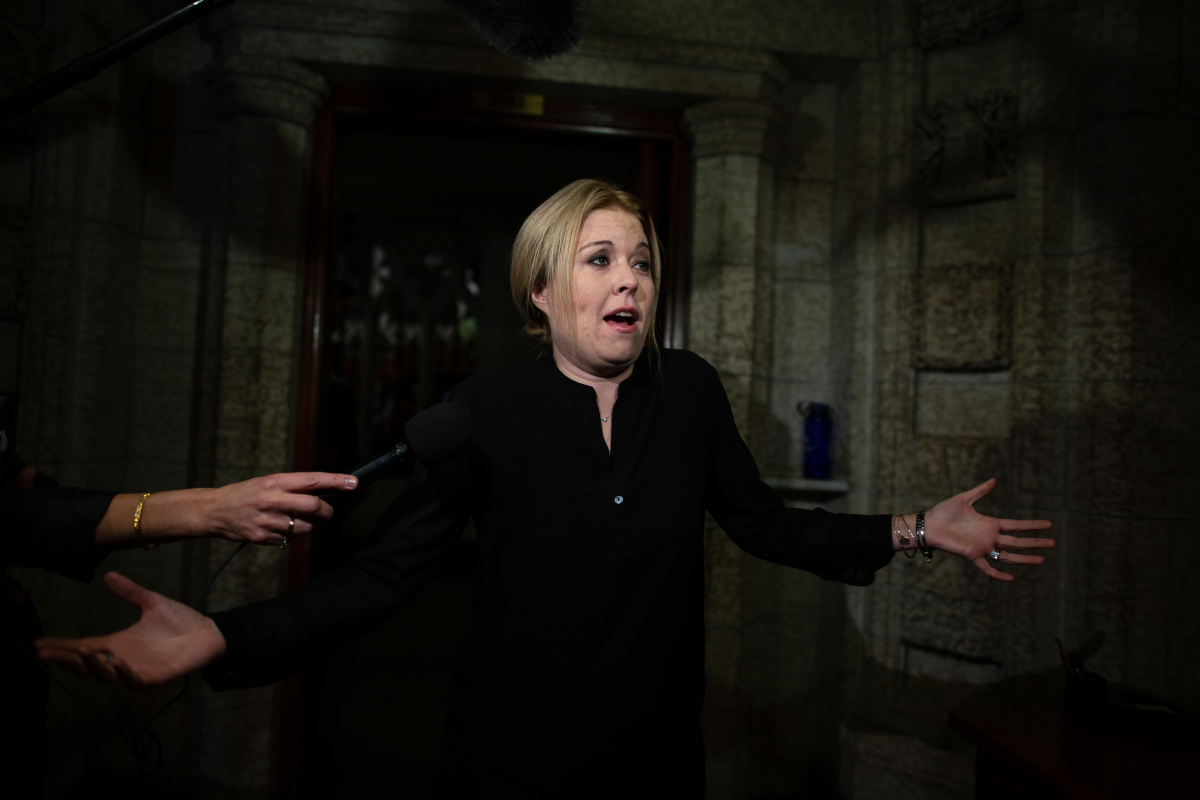

In the polarized, fast-paced world of Canadian politics on Twitter, people who’ve been blocked by Calgary MP Michelle Rempel, the Conservative immigration critic, frequently post using the hashtag #BlockedByRempel.

Aditya Rao, a 30-year-old Ottawa-based immigration lawyer, is one of them. He says Rempel blocked him in August 2018 after he compared her use of the phrase “anchor babies” — a derogatory term used to refer to children born to non-citizen mothers who travel to give their children birthright citizenship in a different country — to Donald Trump, who often uses the saying.

“Michelle Rempel is going full-Trump with her campaign to stop asylum seekers from finding safety,” he tweeted.

Rempel didn’t respond to requests for comment, but members of Parliament aren’t governed by any rules that bar them from blocking people on social media. The issue falls outside the scope of the federal conflict of interest and ethics commissioner, and in a statement, the commissioner’s office said it had never received a complaint about this issue.

Rao said although he isn’t one of Rempel’s constituents, it’s difficult for him to do his job properly if he can’t see what the immigration critic is saying about the area of law he specializes in. Though he can see Rempel’s tweets by logging out or going on a different account, it’s “frustrating” in principle, he said.

“Given how fundamental Twitter has become for better, perhaps arguably for worse, democratic discourse, I just feel like restricting access to politicians speaking on Twitter is not a decision that should be taken lightly,” Rao said.

“It’s in the public interest to ensure that politicians are able to be held accountable, rather than just continually get amplified in their own echo chambers and create the exact kind of polarization that we're trying to avoid.”

Comments

I consider the fact that Jason Kenney has blocked me on Twitter for years a badge of honour. Through it I share a little something with the great British politician George Galloway. When Kenney was immigration minister he tried to prevent Galloway from coming to Canada to speak against the war in Afghanistan. A war which Kenney seemed to love. Last month Kenney engaged in a stunt involving handing out ear plugs in the legislature while NDP members were speaking. That sort of disrespect for democracy was typical of the despicable Harper government in which Kenney 'served'. If you refuse to listen to the loyal opposition you may as well prorogue, as Harper once did to avoid defeat.