Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Fact or fiction: earlier this month, scientists from a respected university told us that recent record-breaking wildfires in British Columbia have been used to model the effects of nuclear war on our planet’s climate?

It might be tough to guess, given the rising popularity of speculative “cli-fi” (climate fiction), but it’s a true story.

The 2017 B.C. wildfires emitted the largest-ever observed pyrocumulonimbus cloud (PyroCb) — wildfire-induced thunderstorms characterized by plumes that form when the heat from wildfires sends smoke and soot high up into the atmosphere.

That data is helping to validate the climate models of scientists at Rutgers University who are trying to forecast how smoke from burning cities and industrial zones would act in the event of a nuclear war. (Spoiler alert: the cooling effect of soot that lingers in the stratosphere for months wouldn’t be good for our food security or well-being.)

Think this stranger-than-fiction tale needs more adrenaline? Well, buckle up.

Beating the roughly less than 50-50 odds of getting a chance to actually sample one of these “fire clouds,” NASA just made a rare flight right through one. The reconnaissance mission made meteorologist David Peterson one of the only people on the planet to do so. In the process, he made observations and collected samples to help researchers better understand how PyroCbs affect our climate.

Meanwhile, the “Doomsday Clock” measuring humanity’s proximity to destruction has been set at two minutes to midnight (where midnight is game over) for the second year in a row. The time, set by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, draws attention to “the devolving state of nuclear and climate security.”

As climate change fuels worsening wildfires, it’s no wonder that scientists are working to unravel some of the mysteries about how PyroCbs behave and how they impact us. The wildfires burning in the Arctic have been named the worst on record. Greenpeace Russia has found that more than five million hectares of Siberian forest remain aflame (imagine a blaze bigger than Vancouver Island). Experts have named climate change as a factor. Canada has so far been spared the worst of it, though smoke from the Siberian fires did reach us. Yet scientists at the University of Victoria have determined that climate change likely made the area burned in B.C.'s 2017 wildfires seven to 11 times larger than expected.

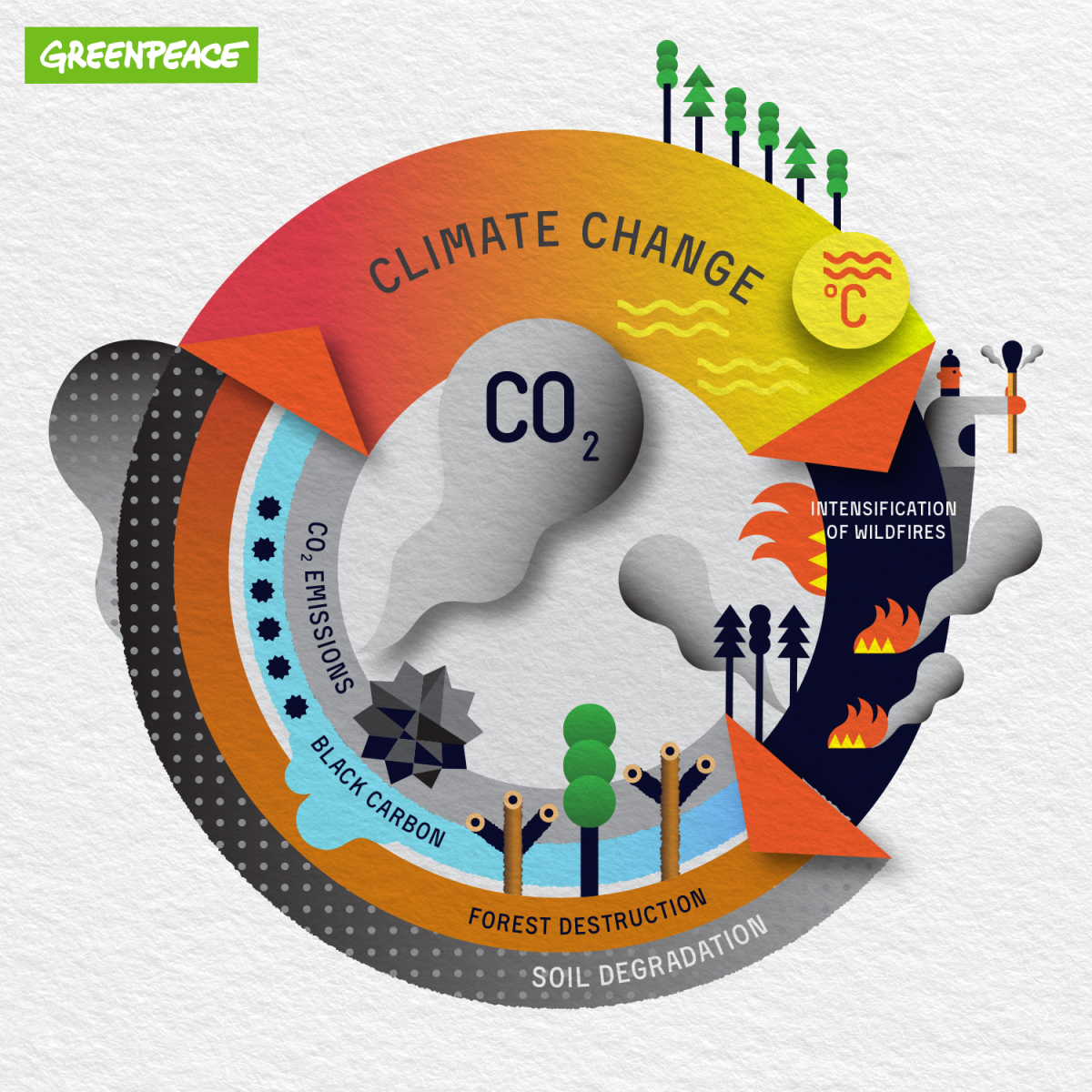

The heebie-jeebies of climate-fuelled wildfires being used to model nuclear winter aside, extreme wildfires are also part of a harmful feedback loop impacting climate change.

Since forests absorb carbon dioxide over time, wildfires can release a large amount of climate pollution in a short amount of time. But carbon dioxide isn’t the only pollutant putting pressure on the Arctic.

Greenpeace experts monitoring via satellite have been studying the effects of black carbon, the heat-absorbing soot produced by wildfires, as have scientists involved in the Rutgers study and the NASA flight. Only a relatively small amount of black carbon is produced, but it has a strong effect on global heating and is a contributor to climate change.

Black carbon can drift thousands of kilometres over days and weeks and settle in the Arctic. Normally, the bright Arctic ice keeps cool by reflecting up to90 per cent of the sun’s energy back into space. But when black carbon settles, the dark colouring causes more of the sun’s energy to be absorbed. This can drive the ice, a critical part of our planet’s natural defences against global heating and climate change, to literally melt away. That’s where we see the feedback loop come full circle, as more intense heating contributes to extreme fire weather.

The wildfire cloud in the Rutgers study emitted 0.3 million U.S. tons of soot. Earlier this month, The Guardian and World Meteorological Organization reported that Siberian wildfires have generated a billowing cloud of smoke and soot bigger than the European Union.

Silver linings on clouds like this can be tough to see, but there’s still time to solve the climate emergency.

The biggest fossil fuel polluters like the oil, gas and coal industries have been responsible for the majority of the human-caused emissions that triggered the climate crisis. We believe that with transformative action to clean up our energy system and implement the Green New Deal, we can cut our emissions in half in the next decade. This could have a positive effect on reducing extreme weather risks, but we need the political will to do it.

Industry and governments must, as Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg has put it, “act like the house was on fire, because it is.” Instead of adopting policies that would burn the house down, Canada and the international community should take up the tools and knowledge we have to put out the flames — because we still can.

Jesse Firempong is the wildfires-response lead at Greenpeace Canada.

Marina Drozdovskaya is the Greenpeace Russia fire project lead.

Comments