Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

The man who shot and killed nine people outside of a nightclub in Dayton, Ohio, on Aug. 4 reportedly had an extensive history of violence and threats against women.

According to Vice News, he was also “deeply involved" in a disturbing part of the extreme metal music scene known as “pornogrind,” which is characterized by sexually violent lyrics and albums featuring dehumanizing images of women and women’s body parts.

Meanwhile, the gunman who killed three people and injured 13 others at a festival in Gilroy, Calif., a week earlier was found to have posted messages online referring to a misogynist, white supremacist manifesto.

Recent acts of mass violence in the U.S. have shone a spotlight on the link between misogyny and extremism across the world. And Canada has its own unique problems with misogyny and extremism that have surfaced in recent years in a bout of attacks.

Public Safety Minister Ralph Goodale commented on this link pertaining to events in the U.S. and Canada on Aug. 6 in a press conference, when asked about whether the spate of mass shootings made him concerned about white nationalism in Canada.

“At least in some of those cases, it’s pretty apparent from the evidence available so far that there were strains of right-wing extremism and violent extremism that laid the foundation and contributed to that behaviour,” Goodale told reporters.

“When you think of the circumstances that have caused serious and tragic losses of life in Canada, the pattern is disturbing,” he added. “If you go back far enough, the shootings at École Polytechnique and at Dawson College were acts of misogyny that has its roots in that kind of extreme right-wing mentality.”

“Yes, we are concerned about that trend that you see in places like Christchurch, for example, or Pittsburgh with the synagogue, the Tree of Life synagogue last year, and other locations around the world, but it has happened in Canada, too,” he said.

Goodale’s comments were the first from a federal minister to make this link — and mark a stark shift from the way the conversation has unfolded thus far.

The 2018 Public Report on the Terrorism Threat to Canada, for example, found that while the threat of violence from those who hold extreme right-wing views can manifest itself as violence, it’s not as serious a problem here. The report found that “while racism, bigotry and misogyny may undermine the fabric of Canadian society, ultimately they do not usually result in criminal behaviour or threats to national security.”

But in an email to National Observer, Goodale’s office made clear that times have changed.

“Daesh and al-Qaida are (not) the only sources of dangerous extremist violence. It can come from any type of fanaticism,” the email said. “Of increasing concern are groups like right-wing white supremacists and neo-Nazis who foment hate, which manifests itself in violent anti-Semitism, or a brutal misogynistic van attack along Yonge Street in Toronto, or the murder of six Canadian citizens near Quebec City, only because they were at prayer in a mosque.”

The new word in this statement is “misogynistic.” There is growing recognition of the connection between misogyny and extremist violence, but experts around the world continue to say the threat is still underestimated.

Is that changing in Canada?

The ‘manosphere’

As far-right movements come under increasing public scrutiny for their role in the rise of hate crimes and extremist violence, there remains a notable lack of attention in Canada to another common thread linking the incidents: a history of misogyny, often expressed both online and in real life.

“Few have been willing to name white male violence as a source of national security concern, even though evidence suggests that right-wing extremism and white power ideology have been on the rise for years,” Faisal Bhabha, associate professor at Osgoode Hall Law School at York University, told National Observer.

This was the case in April 2018, when Alek Minassian drove a van onto a crowded Toronto sidewalk, killing 10 people and wounding 16 others. Prior to carrying out the attack, Minassian left a Facebook post calling for an “Incel Rebellion” and praising Elliot Rodger, another self-described incel-turned-killer.

Incel, shorthand for “involuntarily celibate,” is a term associated with the male supremacist movement, which the U.S.-based Southern Poverty Law Center describes as a hate-based ideology whose adherents “consistently denigrate and dehumanize women, often including advocating physical and sexual violence against them.”

After the van attack, incels flooded online forums to discuss the rampage — even going as far as to celebrate Minassian’s actions, replacing their avatars with his image and calling for others to follow in his footsteps.

But at the time, Canadian authorities said they didn’t consider the attack a national security threat, despite a record that suggests otherwise.

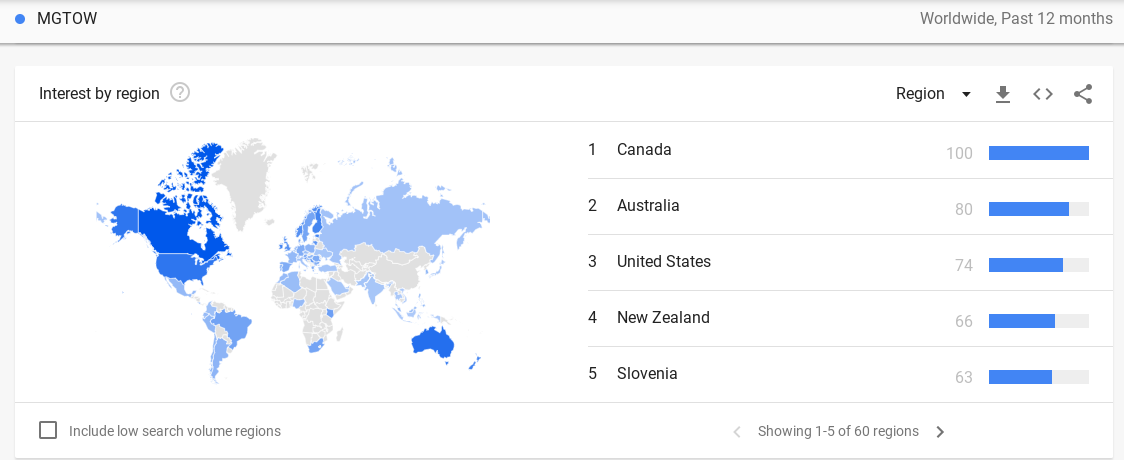

Canada occupies a unique space in the so-called “manosphere” — a collection of blogs, websites and forums frequented by misogynists, anti-feminists and men’s rights activists. According to Google Trends, Canada tops the list for global interest in the anti-woman movement known as Men Going Their Own Way (MGTOW). Men who identify with the MGTOW movement swear off relationships with women entirely, often citing resentment and grievances with women in their lives as the motivation.

Canada is also the birthplace of the incel movement. A Canadian woman who wanted to create an online support community for people struggling to form long-term romantic relationships first used the term “incel” in the early 1990s. At the time, the term was used to refer to both men and women, but its meaning has radically changed over the years.

The term “incel” as we know it today entered the popular lexicon in 2014, when 22-year-old Elliot Rodger of Isla Vista, Calif., killed six people and injured 14 others before killing himself in a mass shooting that made headlines around the world. After the shooting, it was discovered that Rodger had an extensive presence online, where he self-identified as an incel. He left behind a series of YouTube videos describing his hatred toward women, the last of which, called "Elliot Rodger's Retribution," was recorded immediately before the killings. He also left behind a 137-page manifesto describing his resentment and anger toward women for not sleeping with him, which he said motivated him to kill.

Marc Lépine, who killed 14 women and injured 10 other women in a shooting at Montreal’s École Polytechnique in 1989, is often cited on incel forums and message boards as the first known incel killer in modern history.

There is growing recognition of the connection between misogyny and extremist violence, but experts say the threat is still underestimated.

“This is a serious concern,” McMaster University sociology professor Tina Fetner told National Observer about the muted response to misogyny-fuelled violence. “In my opinion, neither police nor the (government) are taking it seriously enough or addressing it adequately.”

Acts of violence associated with the MGTOW and incel movements are still often portrayed as “lone wolf” attacks, but in many cases, the men are motivated by a shared ideology that comes straight from forums and online message boards. Often, the so-called “manosphere” acts as a funnel into the more extreme fringes of the internet, where young men are introduced to white supremacist, neo-Nazi and other extremist ideologies.

These extremist communities appeal to aggrieved young men for the same reason misogynistic ideologies are appealing: they offer up a scapegoat for their problems, often in the form of vast conspiracies alleging that women and minorities are responsible for oppressing white men.

Men who identify with the MGTOW, incel and other male supremacist movements tend to share a similar set of grievances and sense of entitlement. Many of these men feel they’re being left behind, and they blame women for doing it — just as white supremacists blame immigrants for taking jobs they believe they are entitled to have.

According to Fetner, “the beliefs of far-right extremists are driven by anger in response to seeing women, racial/ethnic minorities, religious groups and LGBTQ people making advances” — a phenomenon she described as “status loss.”

“White men’s status at the top of (the) social hierarchy is not in fact under much threat,” Fetner said. “However, as women, immigrants, religious minorities and visible minorities have made some modest gains (without achieving full equality), the perception that white men have lost their place at the top of the social hierarchy has gained traction among some groups.”

As a result, some men have gone looking for a scapegoat on which to blame their problems. While this phenomenon isn’t new in itself, the internet — particularly social media — has helped transform misogyny from a world view into a movement by providing a platform where otherwise isolated people can unite and share their grievances. Unlike some supportive online communities where people come together to work through their problems, the forums and message boards that make up the “manosphere” serve as a breeding ground for hate and, at times, violence.

“Far-right communities, mostly on the internet, create and pass along false narratives that support scapegoating groups. They often present false information that exaggerates women’s power relative to men’s,” Fetner said.

“Without regulations addressing the circulation of dangerous, false narratives, it is easy for people to become convinced that the ‘facts’ support the idea that white men are under attack, when the reality is quite different.”

Both Fetner and Bhabha agreed that misogyny-fuelled violence is a pressing national security concern. But historically, Canada’s national security agencies have overlooked domestic threats in favour of prioritizing Islamic-inspired terrorism, Bhabha said. He doesn’t believe that we need new laws to address the scourge of misogyny-fuelled violence.

Rather, he said, “the way to combat violence against women is to address the underlying social causes of violence.”

With files by Fatima Syed

Comments

Canada is also the country that studied the problem of missing and murdered native people for years and missed two thirds of them because they are male.

Missing and murdered male indigenous people, may indeed be the victims of racial violence. Missing and murdered indigenous women are without doubt the victims of sexism, genocidal racism and just plain old, run of the mill misogynist violence. A triple existential threat you might say.

The underlying threat all our native people face has been the colonial genocidal impulse that has spawned all of the disproportionate statistical evidence of their untimely demise.

The lesson to be taken from the MMIW commission is twofold, Being an indigenous woman puts one at greater risk than even a ``white`` woman routinely faces. AND, that being an indigenous person is orders of magnitude more dangerous to health and wellbeing, than being ``white``.

I was hoping for a deeper dive into Canadian groups and individuals peddling misogyny. For example, at its peak, U.S. hate group/site A Voice For Men had a disproportionate number of Canadian contributors and a disturbing number of them were women, including now-retired senator Anne Cools. Another notable alumnus is Stefan Molyneux. There were/are so-called men's rights groups in Edmonton, Halifax and Toronto that received scant media attention.

It's one thing to note the prevalence of MGTOW in google searches but it leaves the cause of it unexplained. It's very frustrating to those of us who have watched this unfold since 2014 along with the authorities downplaying it. I strongly disagree that “the way to combat violence against women is to address the underlying social causes of violence.” We already have a good idea what the causes are and it'll take generations to change sexist attitudes. In the meantime, people are dying. Men in power need to start listening to women.

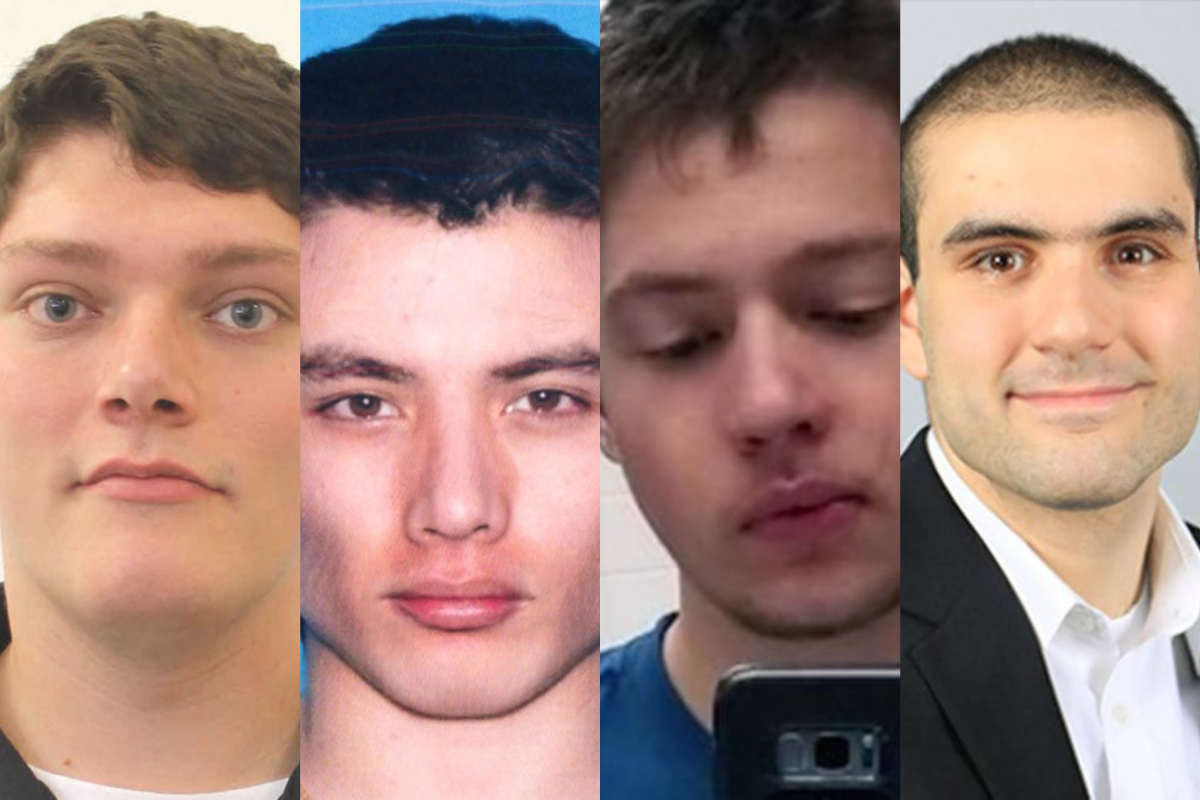

Note to editor: The photo caption has the names of Legan and Rodger reversed.

Thank you for the correction re: the photo caption, Heather, and for taking time to convey your feedback regarding the article and historical context. We've changed the name order.

Thanks, Jenny. Is there a better way to report errors?

Thank you for pointing out the important connection between white supremacist racism and misogyny. Men without access to women cannot reproduce their own kind. Incel thus results in hatred of and often violence against women and minorities.

Misogyny is both a global and ancient phenomen among humans. All the other violance promoting "isms", and "ists", seem to grow out of the same evolutionary human fear of "the other" - which of course, includes females as the original "other", Among men, the hormone driven urge for dominance may well be an evolutionary dead end. Escalating male violence is often vented against other men and in the millennial long history of humanity it would be hard to estimate or compare the casualties on the basis of the victims' genders.

The distinction between male violence against men and women is that the contest between men is generally one of relatively equal strength, whereas the violence men feel entitled to visit upon women and children is grossly unequal. And, in the era of lethal weaponry, the violence that men visit upon humans AND animals for sport or profit is exponentially more destructive.

The links in male violence are known to escalate from animal abuse/killing to females and children and finally to other men. It is a progression too common to engender much concern among the male dominated establishment that thinks itself immune; until it reaches the extremes that arouse their own sense of self preservation.

I think atomization and social alienation as well as unrealistic presentation of machismo in entertainment media preserves the control of the masses through ideology. The idea that real men don't cry should be interpreted as men don't have feelings which makes them stoic warriors. How does being a stoic warrior benefit men in general? How does being competitive and striving for top position value the lives of those who are not at the top? We now know that power for power's sake is worshipped and those who do not have power are sacrificed to the god of power. These trends are as grotesque as the Nazi values in the 30's.