Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Environmental experts agree Canada is in unprecedented, historic territory: it's the first time we're having an election with such a focus on the climate crisis.

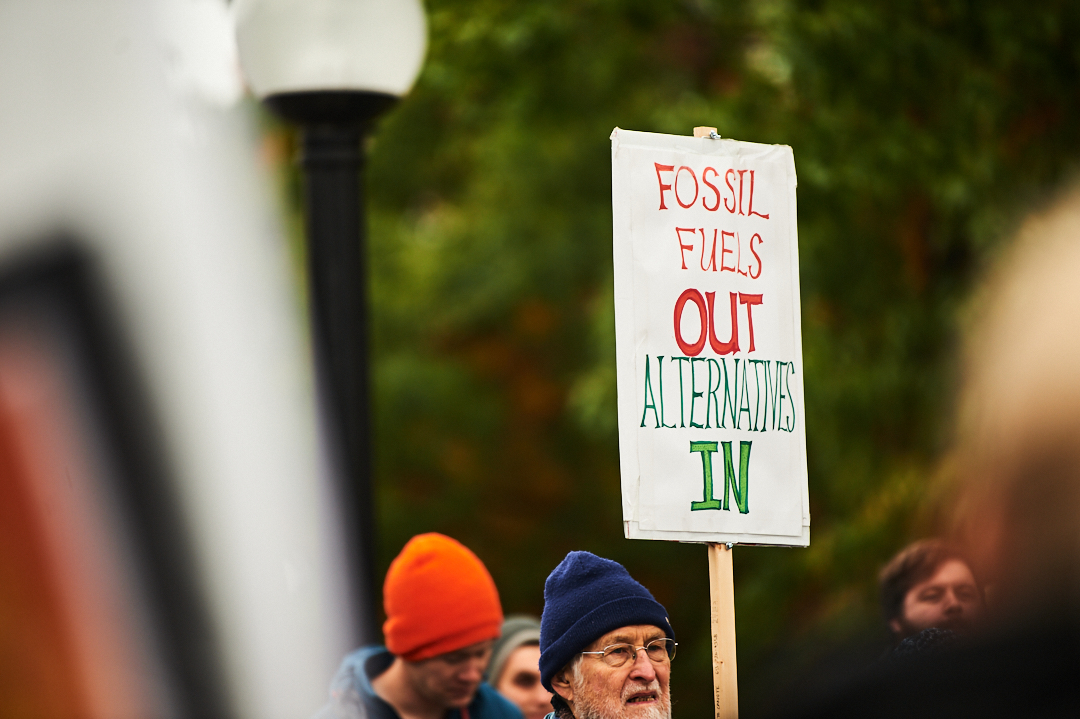

But environmental experts also agree on something else: our climate conversation has failed to envision a Canada without "a fossilized-energy future."

"In this country, we've got our heads in the oilsands," Angela Carter, associate professor of political science at the University of Waterloo and researcher with the Corporate Mapping Project, said in an interview.

"I feel like in Canada, we're not able to have what young Greta (Thunberg) from Sweden would say is the 'adult conversation.'"

Much of the public debate about energy this election has been limited, according to several experts National Observer spoke to, focusing on how to decrease emissions of the oil and gas industry (the biggest polluters in the country), as well as decreasing emissions across the board, without considering seriously changing the foundation of Canada's oil-dependent economy.

The underlying assumption of the public discourse this election, according to Carter, is that Canada can continue on with the status quo: fossil fuel development.

"Oil is part and parcel of our political, economic and cultural framework," Carter said. "It's been fostered by governments and by industry to try to convince Canadian voters there's only one option here. It's fossil fuels forward only. There are no new development ideas."

This is not new, Carter said. For half a century, Canada has funded the fossil fuel industry through financial subsidies, tax breaks, royalty breaks and more, she said.

And as countries around the world start the process of banning fossil fuel exploration and extraction and shift to solar, renewable and battery storage, and banks worldwide withdraw funding for fossil fuel projects, Canada hasn't mustered the ability to have a serious discussion about the same initiatives.

"If we had the same level of attention and support for the renewable sector, building retrofits, electrified public transit, I think that we could do a lot more than we think we can right now," Carter said.

The inherent problem is that, globally, the climate conversation has been focused on "getting carbon out of the atmosphere or greenhouse gases out of the atmosphere," said Dr. Gail Krantzberg, professor of engineering and public policy at McMaster University.

Leaders on the campaign trail have framed their own policies about climate efforts around targets. This was evidenced strongly during the Oct. 7 leaders' debate, during a segment that saw Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau and Green Leader Elizabeth May get into a heated exchange about emissions-reduction targets and whose were stronger.

"Your goal is a target for failure," May said, critiquing Trudeau for matching former prime minister Stephen Harper's target of 30 per cent reductions by 2030.

"We're going to pass that, Ms. May," Trudeau responded.

"Well, you'd better double that," May retorted.

Part of the reason for this narrow focus just on carbon-emissions reductions is the focus on the Paris agreement, which compelled countries to make promises about per cent reductions, Krantzberg said.

"But we've also seen IPCC reports come out since then that talk about land, that talk about oceans, that talk about adaptation. So why is that not entering our conversation?"

What the party plans don't propose

In a Sept. 2019 Science magazine report, scientists found that limiting global heating to 1.5C (as urged by the first IPCC report) will require an annual investment in the energy sector between 2016 and 2050 of around $1- $4 trillion in energy supply and $840 to $1200 billion in energy demand measures in order to reach net zero GHG emissions by 2050.

The damages of not creating such investments would cause hundreds of trillions worth of damages, according to the report, including disruption and migration of human communities; reductions in ecosystem services associated with biodiversity loss.

This "suggests that the potential economic benefits arising from limiting warming to 1.5C may be at least four or five times the size of the investments needed in the energy system until 2050," the report said.

National Observer asked several experts what was missing from the 2019 election's conversation on the climate crisis and most agreed that the scope identified in reports like this one were glaringly absent.

Canada’s electricity grid is already 81 per cent non-emitting, due to an abundance of hydro and nuclear energy. The federal government under the Trudeau Liberals has a plan to reach 90 per cent non-emitting electricity by 2030 by phasing out the last of the country's coal plants.

But experts have said more needs to be done.

This election, all parties have proposed electrifying everything from transportation to the entire power grid, but few speak about "the double-whammy problem" of actually doing that, said Ryan Katz-Rosene, an assistant professor at the University of Ottawa’s School of Political Studies, where he researches and teaches global environmental politics.

When you electrify everything, you need more electricity than Canada currently produces.

"What we're not talking about is making the major capacity increases that would be required on the electrical system," he said.

To accomplish any of the parties' electrification plans, Canada needs to have "two revolutions," Katz-Rosene said.

The first will be a revolution that will clean the electricity grid and upgrade all related infrastructure to increase capacity while keeping emissions low. The second revolution will involve changing consumer habits to make it easier and more feasible for families to purchase electric vehicles and manage electrical costs.

"I think that's one thing that we're we're not seeing a lot of nuance about," Katz-Rosene said. "They don't talk about how much harder it's going to be in 2030 or 2050 without these changes."

Nicholas Rivers, Canada research chair in climate and energy policy and an associate professor at the University of Ottawa, said that in all this conversation about the green transformation in the electricity sector, little has been said about renewable technologies such as wind power, solar and zero-emissions aluminum.

"There's a lot of exciting technological developments that leave reason for optimism, but we're not talking about them in detail here," Rivers said.

Dr. Catherine Potvin, Canada research chair in climate change mitigation and a biology professor at McGill University, said she worries about the lack of conversation around what a carbon budget — a tolerable quantity of greenhouse gas emissions that can be emitted in total over a specified time — should look like in Canada and how it should function.

"No party platform tells me what happens — how their climate promises decrease emissions and by how much," Potvin said in an interview. "Nobody tells me how a credit for innovation will allow me to build this many net-zero houses, or so forth. This kind of thing doesn't exist in Canada because we don't have the data to make these calculations."

At present, the Liberals and Conservatives have agreed to try to hit existing Paris commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 30 per cent by 2030. (Although the Liberals have suggested they’re trying to exceed the Paris targets during the campaign.)

The Green party and the NDP have promised to be more ambitious.

“Canadian governments have a terrible record at hitting their climate targets,” Rivers said. “What matters is what impact the policies will have on these emissions.

“We should be pretty cautious, because we haven't got a great deal of data to look at in terms of what the effects of these policies will actually be.”

'Things are changing more rapidly than we imagined'

The Conservatives and Liberals are similar as far as energy policies go, Carter said, as they are "keeping us locked in that kind of past-energy world" by refusing to strongly tackle the oil industry.

Krantzberg agreed, noting some policies proposed by the Conservatives don't make sense. For one, they have proposed an energy corridor without providing much detail.

The McMaster engineering professor said the corridor "sounds like you're shipping energy around the place," or "a pipeline taking oil from one part of the country to another part of the country."

"What experts in this field are calling for is distributed energy — energy created locally to service the local community," Krantzberg explained. "So solar, geothermal wind — whenever that is feasible — would be set into a local, decentralized place. In other words, the whole notion of putting a bunch of power conveyances in long distances means that you're feeding into a system that is inefficient. You lose the energy as it gets into the grid.

"Things are changing more rapidly than we imagined."

Carter said the NDP and Greens are "proposing a much different energy future for Canada."

"The NDP and Greens are seeing the writing on the wall, which is that confronting the climate crisis means confronting the oil and gas sector," she said.

For Carter, the best-case scenario on Oct. 21 would be to see an election outcome that allows Green and NDP policies to come to the foreground. "Then we can start making the conscious public investments that get us toward decarbonization, and getting us away starts with turning away from fossil fuels and toward where the future is just transition or Green New Deal."

Krantzberg said that, at the end of the day, none of the parties have a "well-defined, concrete action plan" for tackling energy and environment issues.

"I want to see a leader who shows the commitment that this is a No. 1 priority of government," she said. "(A leader) who can confidently say, 'We're going to try new things, and guess what, folks? If they don't work, we're going to try something else until we get it right.' That would be language that I would really support because that would be an honest politician, speaking truth."

Comments