Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Superbugs are likely to kill nearly 400,000 Canadians and cost the economy about $400 billion in gross domestic product over the next 30 years, warns a landmark report.

An expert panel cautions in "When Antibiotics Fail: The growing cost of antimicrobial resistance in Canada" that the percentage of bacterial infections that are resistant to treatment is likely to grow from 26 per cent in 2018 to 40 per cent by 2050.

This increase is expected to cost Canada 396,000 lives, $120 billion in hospital expenses and $388 billion in gross domestic product over the next three decades.

"This is almost as big, if not bigger, than climate change in a sense because this is directly impacting people. The numbers are just staggering," says Brett Finlay, a University of British Columbia microbiology professor who chaired the panel, in an interview. "It's time to do something now."

The Public Health Agency of Canada commissioned the report on the socio-economic impacts of antimicrobial resistance and the Council of Canadian Academies assembled the independent panel. The 268-page document released Tuesday represents the most comprehensive picture to date of the country's resistance rate as well as its costs to the health system and economy.

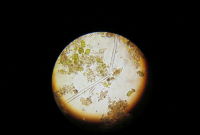

Antimicrobial resistance occurs when micro-organisms, including bacteria, viruses and fungi, evolve to resist the drugs that would otherwise kill them. Unnecessary antimicrobial use in humans and agriculture exacerbates the problem and widespread international travel and trade help resistant bacteria spread across the globe.

The most common antimicrobials are antibiotics, which treat infections caused by bacteria. The report focuses on resistant bacteria but uses the broader term antimicrobial because surveillance data tend to be collected under this heading.

An investigation by The Canadian Press last year revealed Canada has been sluggish to act on the growing threat. At that time, the federal government did not know how many Canadians were dying of resistant infections and it had not produced a plan that lays out responsibilities for provinces and territories.

A pan-Canadian action plan has still not materialized, but the new report estimates an annual death toll in Canada. The panel used the current resistance rate of 26 per cent to calculate that resistant infections contributed to over 14,000 deaths in 2018, and of those, 5,400 were directly attributable to the infections — only slightly less than those caused by Alzheimer's disease.

The panel's economists used a more cautious model to project the impacts than a well-known international report by British economist Jim O'Neill, which predicted up to 10 million global deaths annually by 2050.

The Canadian report's findings on the economic and social toll of antimicrobial resistance are stark. Currently, the problem costs the national health-care system $1.4 billion a year and by 2050, that figure is projected to grow to $7.6 billion, the report says. The cost to GDP is expected to jump from $2 billion to up to $21 billion annually.

Resistant infections decrease quality of life while increasing isolation and stigma and the impact will be unequally distributed as some socio-economic groups are more at risk, the report adds. These groups include Indigenous, low-income and homeless people, as well as those who travel to developing countries where resistant microbes are more common.

"Discrimination may be targeted at those with resistant infections or deemed to be at risk of infection," the report warns. "Canadian society may become less open and trusting, with people less likely to travel and more supportive of closing Canada's borders to migration and tourists."

Antimicrobial resistance has the potential to impact everyone, Finlay says.

"It's going to change the world," he says. "We all go to hospitals and we all get infections."

The report notes that resistance could increase the risk and reduce the availability of routine medical procedures including kidney dialysis, joint replacement, chemotherapy and caesarean section. These procedures all carry a threat of infections for which antibiotics are commonly prescribed.

Limiting the impacts of antimicrobial resistance requires a "complete re-evaluation" of health care in Canada, the report concludes.

The panel states that Canada lacks an effective federal, provincial and territorial surveillance system of antimicrobial resistance and use, with little comprehensive data describing the number of resistant infections and their characteristics.

It also calls for improved stewardship involving careful use of antimicrobials to preserve their effectiveness, strict infection prevention and control through hand hygiene, equipment cleaning and research and innovation for new treatments.

The report notes it's unlikely that new broad-spectrum antimicrobials will be discovered. None have been found in decades and there's little profit incentive for pharmaceutical companies to invest in drugs that quickly cure patients. However, the panel calls for more flexible regulations and incentives to promote discovery of new antimicrobials that treat infections caused by specific bacteria.

Alternative therapies are also being developed to treat or prevent resistant infections, including vaccines and treatments using phages, which are viruses that attack bacteria, the report adds.

Canada should immediately invest $120 million in research and innovation and up to $150 million in stewardship, education and infection control, matched by the provinces and territories, says Dr. John Conly, a panel member and University of Calgary professor specializing in chronic diseases.

The government and public should "absolutely" be as concerned about antimicrobial resistance as they are about climate change, Conly says.

"It's a slow-moving tsunami. Like a tidal wave, it's out at sea but it's going to land on us much sooner than climate change."

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Nov. 12, 2019.

Comments

I fail to grasp the need for this type of fear propaganda. Is it useful for the public - me - to be aprised of these conjectures? What can I do about any of this information? It is the first time (in a few years of subscribing) that I have this reaction to an editorial. It leaves me very uncomfortable.