Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

Boreal caribou have been declining for decades, but public awareness and government action doesn’t seem to change, according to Rachel Plotkin, a caribou expert with the David Suzuki Foundation.

Now, the foundation has created an interactive map that visualizes the impact of human activity on caribou habitat. They spent three months building the map using data from the federal and provincial governments, as well as non-profits like the Canadian Wildlife Federation and Global Forest Watch Canada.

There are 34,000 boreal caribou that continue to live across the country. The World Wildlife Foundation estimates their population has declined 30 per cent over the past two decades.

The map, launched on Tuesday, shows a correlation of weaker populations and more degraded forests with higher levels of oil-and-gas activity around the northern border between British Columbia and Alberta. In 2016, there were 728 boreal caribou across five herds in northeastern B.C.

Plotkin said experts hold the data necessary to enforce solutions to save caribou, such as setting limits on logging and investing in reforestation. She hopes that with all the data in one place, people will see that.

“We have the knowledge to manage caribou for survival. We just need the political will to do it, and the public support to do it,” she said.

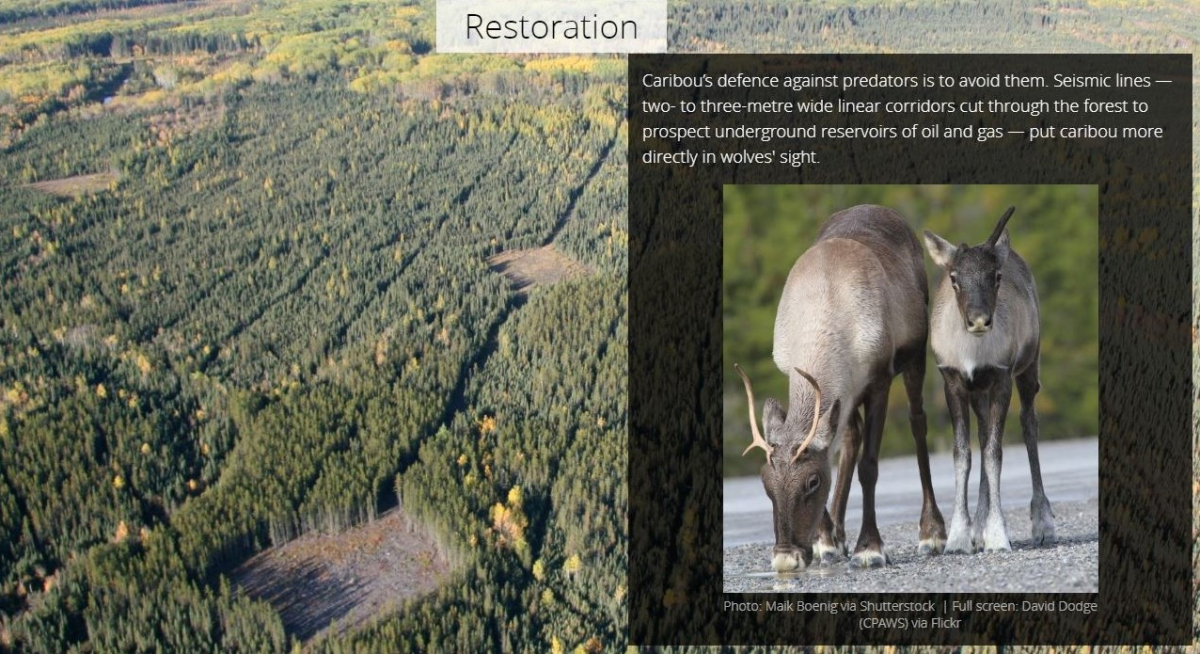

The David Suzuki Foundation’s GIS expert Willem Van Riet said the decline in caribou population is largely due to seismic lines, which are clear-cut corridors made for oil and gas exploration.

“Seismic lines allow predators,” he said.

Boreal caribou usually shyly hide away deep in undisturbed forest. But, says Van Riet, they are more easily found by predators thanks to these corridors. This is especially dangerous for mothers and their calves, because mothers break away from the herd with their young for a few weeks or months, leaving them more vulnerable.

These seismic lines, they really are everywhere. That shocked me,” said Van Riet.

Logging, mining and dams have also caused damage to the boreal forest.

The interactive map includes an image of Blueberry River First Nations. As of 2016, active oil and gas tenures cover 70 per cent of their traditional territory. Between 2013 and 2016, 9,400 kilometres of seismic lines and 290 cutblocks destroyed forest in their territory.

Chief Marvin Yahey is suing British Columbia for the cumulative damage industry has caused on their land over the last fifty years, arguing it broke the treaty they signed in 1900 that promises Indigenous people the right to continue fishing, trapping and hunting, and grants the government permission to use the land “from time to time.” The Observer was not able to reach Yahey before publication.

Indigenous leadership is one of the solutions that Plotkin believes can save the caribou. As well, she calls on provinces to meaningfully protect their forests.

In 2003, Boreal caribou were listed under the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA). And, in 2012, the federal government directed provinces to develop caribou range plans that protect a minimum of 65 per cent of caribou habitat. But a 2018 evaluation by the federal government found none of the provinces and territories that are home to the caribou (B.C., Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador, and the Northwest Territories) have constraints in place consistent with SARA.

Earlier this year, former environment and climate change minister Catherine McKenna warned the B.C. government she could issue an emergency order if they continue to delay implementing a caribou range plan.

Plotkin said restoration of damaged habitat is another important solution, as well as calling on industry to consider conservation as a complementary interest, not an adverse one.

“We’re not looking for industry to stop. We’re looking for industry to apply limits,” she said.

She said protecting the caribou and boreal forest is important so the ecosystem can continue to work as it’s meant to, storing carbon, reducing flooding, and purifying air, which are all factors in mitigating climate change. But for her, it’s more than that.

“It’s the idea that we will be vastly diminishing our world that we then hand off to future generations. We hand off a world that we have, to some extent, bludgeoned and stripped of the things that fill it with mystery and majesty and meaning,” she said.

Van Riet said it’s also important to set aside land for animals in case of unforeseen circumstances, like the Big Bar landslide in the Fraser River that wounded an already weak salmon run.

“We shouldn’t manage species to the brink, as we have been. We should manage them so they can be a healthy population that can sustain unknown incidents,” he said.

Comments