Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

After hundreds of years of outside governments and industry cashing in on Indigenous lands and resources with few benefits reciprocated, one organization is setting new precedent that could transform the energy industry.

Armed with the backing of dozens of First Nation members and corporate partnerships, an initiative to create renewable energy projects led by Indigenous groups is aiming to make millions of dollars in Alberta and Saskatchewan. With the growing demand for cleaner energy and power, Indigenous groups are open for business and ready to bring it to market.

“For too long, we’ve had major corporations and entities bring First Nation and Indigenous Peoples along for the ride... that’s not what’s happening now,” First Nations Power Authority (FNPA) CEO Guy Lonechild told an audience of stakeholders at Enoch Cree Nation on Wednesday.

Playing on the sidelines is not on the agenda, he continued — this is a game changer, a win-win that reinforces treaty relationships and helps pave the way for Indigenous self-determination.

More than a handshake

First Nations Power Authority is the only North American non-profit Indigenous owned and controlled organization developing power projects. One of its main goals is advancing Indigenous equity ownership and control on renewable energy projects, from start to finish.

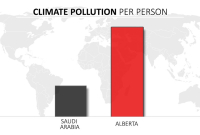

An FNPA forum took place at Enoch, a First Nations community near Edmonton — a place dubbed Alberta’s “oil city.” The oilsands industry that’s sustained the province's growth and wealth creation for decades is facing uncertainty amidst an economic downturn, political barring and environmental scrutiny.

Turning to the prospects of new, greener technology, the FNPA hopes to provide alternative solutions to consumer energy needs. Lonechild says it’s time Indigenous Peoples have the opportunity to benefit through harnessing the resources of their traditional territories.

Partnering with industry and governments is key to launching forward, he said.

“Indigenous engagement (in the energy sector) has to be more than just a handshake. We want to create transformational relationships.”

And that includes owning a majority stake in energy projects, he continued, which will help First Nations get out of the cycle of poverty and take part in the mainstream economy.

Billion dollar fund aims to align Indigenous interests with gas and oil

Meanwhile, another first of its kind is unfolding in Alberta — a billion-dollar fund from the provincial government to advance Indigenous natural-resource developments. It’s an initiative that aligns assistance for Indigenous investment with the interests of the oil and gas industry.

The Alberta government plans to invest the money to support Indigenous participation in natural-resource projects and infrastructure, including pipelines, through the Alberta Indigenous Opportunities Corporation (AIOC), announced earlier this year.

The plan isn’t too promising for the FNPA, which focuses on renewables. That’s because the AIOC money isn’t green.

Nevertheless, Rick Wilson, Alberta's minister of Indigenous relations, was on hand in Enoch to show support for the FNPA and tell attendees they have his moral support.

Wilson became emotional when speaking about the opportunities available to help Indigenous Peoples turn the tide on wealth creation.

“Who were the first people to do business in Canada?” Wilson asked. “Let’s remember the fur trade — it was Indigenous Peoples. Fairness and economic opportunity abounds here, and this comes from taking bold action.”

Even if priority is focused on natural-resource projects right now, once capacity is built to support investment into renewable projects, it will be made available, he explained.

Wilson said Premier Jason Kenney mandated him with achieving “economic reconciliation” and the AIOC fund plays a big role.

“We are trying to heal the (historical) rifts that remain,” Wilson said. “Just trickling in money to them (First Nations) is not good enough. We must move toward economic reconciliation, where Indigenous (Peoples) are not just participants, but partners in prosperity.”

Indigenous Peoples want a “hand up,” not a “handout,” and decisions of previous governments limited them from moving forward economically, he added.

"We're all in this together"

“When First Nation communities thrive, all Alberta thrives. We’re in this together,” Wilson said.

The oppressive regulations of the federal Indian Act already make it difficult for First Nations to get ahead in business, said Indian Resource Council (IRC) CEO Steven Buffalo, who represents First Nation stakeholders in the oil and gas sector. “Our communities are impoverished with little opportunities around them,” Buffalo said. “So the importance of having equity ownership is profound.”

But the transition from oil and gas to renewables isn’t going to be easy on the Prairies, he continued. Although the IRC agrees that transition is the way of the future, they need to keep working with fossil-fuel industries to help ease the process. Even with the help of established partners and outside investors, switching to green is a monumental task.

Going green is hard everywhere, but especially for First Nations, because, he stressed, Indigenous communities lack the resources to completely transition to greener sources of energy. Most First Nation communities struggle with extensive social and economic woes, he said, and building up capacity to transition takes plenty of extra resources that just aren’t there.

The good and the bad industry brings

Buffalo knows the good and bad that industrial development can bring, through lived experience.

The boom of natural-resource development came with a short-lived monetary blessing of royalties given to band members in Buffalo’s home community of Samson Cree Nation, located in the heart of central Alberta, part of the Four Nations of Maskwacis. Now the oil wells are running dry.

In the 1950s, Samson struck oil. It was one of the largest oil reserves discovered in that part of the province, under Maskwacis. The sudden influx and distribution of wealth came with consequences — a rise in violence and suicides was attributed to the discovery of oil there, according to a 2016 report by the Samson Cree band. It’s a narrative that often plays out during boom times in many mainstream communities, which see spikes in addictions, crime and violence when the money flows.

Much of the oil in Maskwacis was extracted by 2000 and band councils stopped annual royalty payments to members in 1998. Still, there is a reliance on oil that’s ingrained within — from on-reserve housing power and heat deficiencies to the federal purses that fund on-reserve programs, because the width of federal budgets depends on oil revenues that are now fading.

But Lonechild wants First Nations to learn from past mistakes of booms on oil-rich reserves that saw royalties distributed, spent and gone when the oil dried up.

Calling the shots

“These large sums of royalties were not sustained. We want to get it right this time and build knowledge through renewable energy.”

FNPA brings a new approach, flipping the scales. This time, the decisions will be made by Indigenous Peoples from the top of the money trail.

The culture behind the business is transforming, he said. Having majority ownership in energy projects will enable Indigenous stakeholders to call the shots on distribution, re-investment and future planning.

FNPA will face challenges in its ambitious goals. The oil industry still rules the land in Alberta and Saskatchewan. Switching to renewables here will happen at a slower pace than in the rest of the country.

The renewable energy market faces stiff competition from the long-standing fossil-fuel industry that’s fighting to stay in the game, said Peter Tertzakian, an economist and author with the Arc Energy Research Institute.

“When trying to push out an established business, they (industry) don’t sit still,” he warned attendees at the FNPA gathering in Enoch. “They become more efficient to diversify the industry. You have head-to-head competition.”

But it’s not about putting the oil and gas sector out of business, assured Glen Pratt, CEO of George Gordon Developments Ltd. of George Gordon First Nation. Instead, he said, it’s about Indigenous sovereignty and reducing emissions with the goal of healing Mother Earth.

“We don’t want people to lose their jobs,” Pratt said. “Indigenous Peoples want to be a part of reducing emissions, but also be a part of the economy to create self-determination.”

A new solar farm for Saskatchewan

George Gordon Developments — along with the economic development brand of Star Blanket Cree Nation in southern Saskatchewan and Natural Forces, a private independent power producer — is constructing a 10-megawatt solar farm near Weyburn, Sask. The Pesakastew Solar Project is set to be up and running in 2020 and will supply clean energy to the Saskatchewan electrical grid. It will provide electricity to approximately 2,400 homes and displace 18,860 tonnes of CO2 equivalent annually. It’s a project that FNPA helped to facilitate.

George Gordon and Star Blanket own 51 per cent of Pesakastew Solar Project. According to Pratt, the project will bring an approximate $750,000 return for all partners.

He envisions George Gordon eventually building a one-megawatt on-reserve solar facility with the money earned from the Pesakastew project. From there, the community would sell a portion of the power generated back to SaskPower and re-invest in energy-efficient community initiatives and social programming.

In May, the FNPA signed a First Nations Opportunity Agreement with SaskPower for 20 megawatts of new utility-scale solar generation projects. The agreement is estimated to be worth $85 million over the course of 20 years. There are dozens of small- to large-scale projects involving solar, wind, biomass, geothermal, battery and other renewable energy technologies in various stages of development, Lonechild said.

Access to capital is one of the biggest barriers for many Indigenous stakeholders wanting to join the renewable resource economic wave — because, unlike most real estate, reserve lands can’t be put up for collateral. That’s where power companies, public and private, along with governments, are invited to get on board, Lonechild said.

In return, corporate entities and governments reap the benefits of consent for industrial development from partnering with First Nation communities who have the land base.

When industry and governments make deals with FNPA members, it’s a partnership that opens the door to a new way ahead — and this time, Indigenous Peoples are calling the shots.

Mike Martelli, president of renewable power for Ontario Power Generation, believes corporations are waking up to the fact that demographics in society are shifting and more industrial projects are spanning Indigenous territories.

“It starts with leadership within the companies,” Martelli said. “No energy project will move forward without the participation of First Nations.”

Comments

This line seems strangely out of place or incorrect...

"The plan isn’t too promising for the FNPA, which focuses on renewables. That’s because the AIOC money isn’t green."

Albert's Oil/Gas industry is, as usual, tone deaf and playing/paying for the wrong team. Indigenous "green"/sustainable/off grid technologies are a natural for their remote and chronically underserved communities and more power to them (pun intended) for their foresight in grasping an opportunity to leap over the "white" domnated power models and develop techonlogies and systems/ expertise in scalable energy production.

Alberta's billion dollar conditional offer seems limp and lifeless in comparison. Where is the vision? where is the imagination? where is the preparation for a future with vastly diminished roles and values for fossil fuels?