Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

This story was originally published by HuffPost and appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration

The sixth Democratic primary debate on Thursday was the first to raise climate change within the first half-hour, but the questions were framed largely around the sacrifices necessary to curb emissions and adapt to already-unavoidable warming.

Should we pay to relocate families from drowning coastal communities? And should we trade America’s oil and gas boom for climate policy, even if it displaces fossil fuel workers?

Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) called for rejoining the Paris agreement and restoring Obama-era regulations. South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg deflected and touted his carbon pricing proposal. Former Vice President Joe Biden said sacrifice was worth the opportunity of green jobs.

But Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) pushed back against the very premise of the question.

“It’s not an issue of relocating people and towns,” Sanders said. “The issue now is whether we save the planet for our children and grandchildren.”

The crowd roared. At 78, Sanders is the oldest candidate in the race. Yet even before the primary contest began, the Vermont senator emerged as one of the most vocal advocates on an issue of top concern to young voters.

Last December, Sanders held a televised town hall event on climate change. In August, he unveiled a $16.3 trillion Green New Deal proposal that included everything from establishing a federally run public option for electricity to spending close to $15 billion on worker-owned grocery stores. In November, the candidate made climate the primary focus of his Iowa campaign in the lead-up to the closely watched first caucus, and also sponsored a sweeping green public housing bill with Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.).

“We’re talking about the Paris agreement, that’s fine,” Sanders said at Thursday’s debate. “But it ain’t enough.”

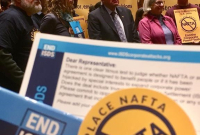

In the past few debates, Sanders beat moderators to the punch in mentioning climate change. He did so again on Thursday night, using an opening question on whether he’d vote for the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement to criticize the fact that the trade deal, dubbed NAFTA 2.0, made no mention of climate change. Sanders called that “an outrage.”

We’re talking about the Paris agreement, that’s fine. But it ain’t enough.

Later in the first round of the debate, Sanders again redirected a question about racial disparity to climate change.

“This is the existential issue,” Sanders said. “People of color are, in fact, going to be people suffering most if we do not deal with climate change.”

When Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s turn came up in the line of climate questions, Tim Alberta, the chief political correspondent for Politico Magazine, asked about the role nuclear energy should play. Nuclear reactors provide the majority of the United States’ zero-emissions electricity. But the high cost of new plants, the toxic waste they produce, and the risk of meltdowns like the 2011 Fukushima disaster in Japan make nuclear power deeply unpopular.

Warren doubled down on her opposition to building new plants. But to stop “putting more carbon in the air ... we need to keep some of our nuclear in place,” she said.

That position separates her from Sanders, who vowed in his climate proposal to shut down existing reactors and refuse to renew licenses for existing plants.

Businessman Andrew Yang took a markedly different tone. He reiterated his calls to invest in new reactors that use thorium, which produces less radioactive waste than uranium, according to the World Nuclear Association, and isn’t used in weapons. The advanced nuclear startup Oklo received a permit from the Energy Department to build a cutting-edge small reactor at the Idaho National Laboratory. In an analysis of whether a Yang administration could bring thorium reactors to fruition by 2027, Wired magazine summed up the prospects with this headline: “Good luck, buddy.”

![U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders speaking with supporters at a campaign rally at the Phoenix Convention Center in Phoenix, Arizona. Photo by: Gage Skidmore. Flickr [CC BY-SA 2.0]](/sites/default/files/styles/scale_width_lg_1x/public/img/2019/12/22/25195805314_6f872e13b5_c.jpg?itok=lDUXK7zM)

Comments