Support strong Canadian climate journalism for 2025

This story was originally published by The Guardian and appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration

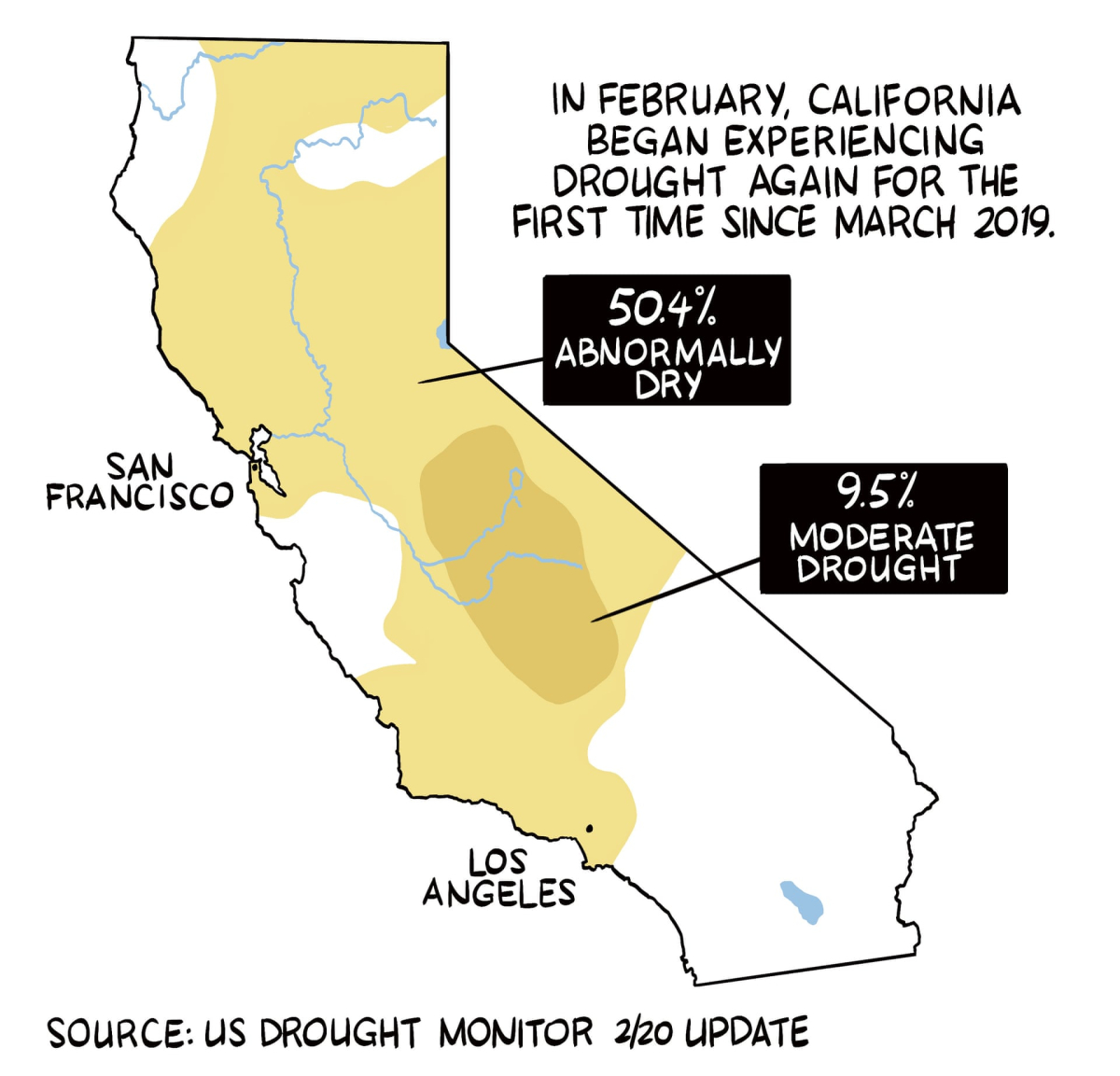

San Francisco and Sacramento have not seen a drop of rain this February, and climate scientists are expecting that disturbing dry trend to hold, in what is typically one of the wettest months of the year for California.

“This hasn’t happened in 150 years or more,” said Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at UCLA’s Institute of the Environment and Sustainability. “There have even been a couple wildfires – which is definitely not something you typically hear about in the middle of winter.”

Combined with warmer than average temperatures, the state is parched, and there is no moisture in the forecasts. “The dryness has picked up as the season has gone on,” said Swain.

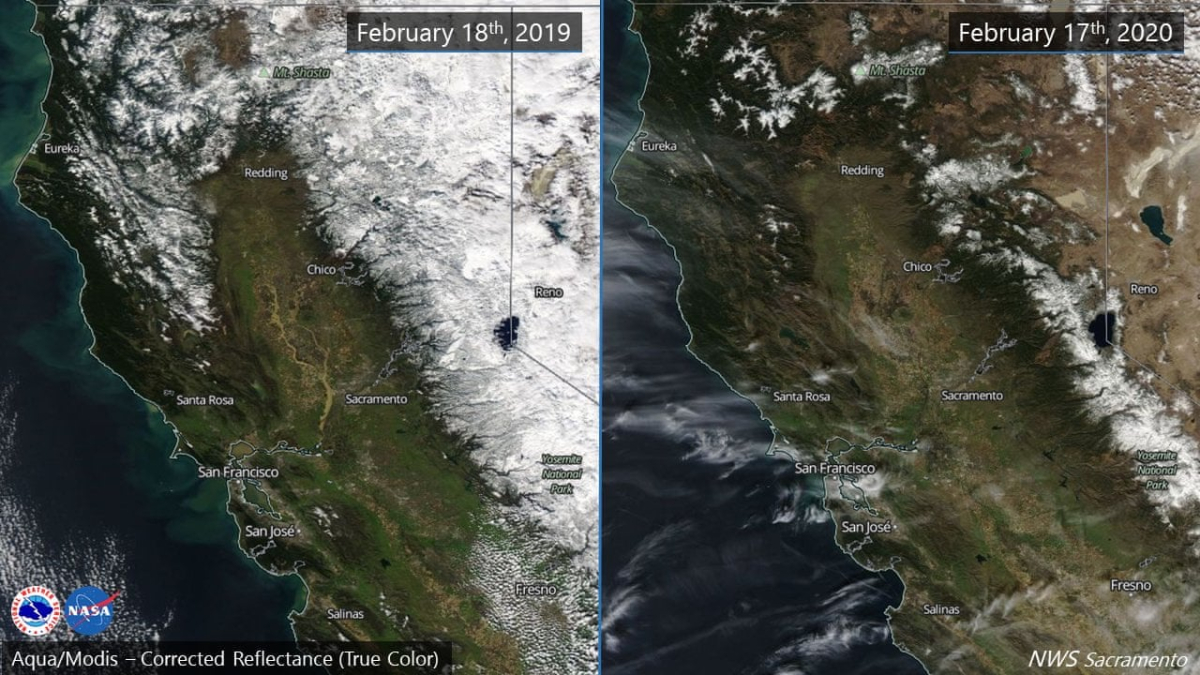

The year began with snowpack at 90% of its historical average. But less than two dry, warm months later, it’s hanging in at just 52% of average.

“Those numbers are going to continue to go down,” said Swain. “I would guess that the 1 March number is going to be less than 50%.”

That snow isn’t just the basis for the mountain tourism industry in the winter – it serves as a significant source of water for California cities and agriculture come spring melt.

Last year’s snowpack at this time was more than 125% of average, an indicator of what Swain calls “precipitation whiplash”. California has long weathered these wet and dry cycles. The state’s future in the climate crisis looks warmer and drier not because of a lack of rain, but because of the extra heat drawing moisture out of the ecosystem. That heat is a major contributor to reduced snowpack, both as less snow falls, and as more of it melts more quickly. Climate science points to a California bound for a future that looks less like endless extreme drought alone.

“We aren’t going to necessarily see less rain, it’s just that that rain goes less far. That’s a future where the flood risk extends, with bigger wetter storms in a warming world,” said Swain.

The 2011-2017 drought was the worst since record-keeping began. It reshaped California’s landscape and its regulations, and memories of water rationing still loom large in the state’s memory.

“Some folks will say you’re not in a drought until there’s water scarcity problems,” said Swain. “We have a fair bit of single-year drought resilience. No matter how severe it is, the cities and most of the [agriculture] zones won’t run out of water.”

The more immediate impacts of this trend will be on the ecosystem and the inevitable fire season, as California’s grasslands and forests continue to dry out.

Comments